More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Her body is a log of all the times she couldn’t be good and patient and just wait for the swelling to go down.

I’m jealous of the way Poppy still thinks that everything she’s ever experienced is special.

Now we’re fighting about nothing, about a detail I made up to pacify her.

“Actually,” Poppy says, “it’s not a story from a friend. It’s just a funny tweet I saw.”

A couple of years ago I used it to hate-stalk the accounts of brands I liked but couldn’t afford, writers who were younger than me but whose careers were so far ahead of mine I’d never catch up, my craziest cousins and their craziest acquaintances, the worst people from high school.

I get ready to explain to Poppy that what I’m doing isn’t about fun, but I stop myself because I don’t know what it is about yet.

I can see the end of art and culture and sometimes even human life if I’ve been scrolling through the right pages for long enough.

Sometimes I feel like my own ancestor. Sometimes I feel like a Tamagotchi.

I don’t want to eat any kind of fish or meat in this place; I don’t like the look of the tabletops.

“Stop making things harder for yourself. Things don’t have to be so hard.”

“I don’t care about spoilers.” Of course, I’m furious that she’s just spoiled the movie for me.

Also, you have this new thing I’m noticing,” Poppy says, moving her hands at me like a mime in a box, “where you don’t think anything means anything.”

I was too icked by the new way Poppy cried: constantly, close-eyed, keening like an old tea kettle.

Poppy wants to be anything her girlboss feminist idols are. A nun like Sor Juana, a showrunner like Tina Fey, a communist like Frida Kahlo.

I stare at the sprinkler pipe running across my ceiling and consider where I am, where I ought to be. In childhood, I thought I’d be an orthodontist.

Every time I think of something I want I manage to talk myself out of it.

I don’t know him well enough to know what kind of face he’s making.

I can’t tell her that I told Jon her biggest secret, or that I did it partly to try to get him to want to take care of me, or that it didn’t even work.

Poppy shuts the window and hands me my pill, firmly this time. The gesture reminds me of our mother.

“The cereal aisle,” she says, “is the most beautiful place on Planet Earth.”

Poppy wants to write a sitcom about us, she tells me.

I understand very suddenly that I won’t be married by the time I’m thirty.

I often wonder if the whole building’s haunted, if they’ve stabilized the rent in case the place is cursed. My life’s certainly gotten worse since I moved in.

I’m feeding something bad inside me: The part of me that agrees with my mother. The part of me that wants to be alone for no good reason.

I feel the top of my head prickle and my pupils embiggen.

At least I’m not one of these people or one of their followers. Then I realize that I am, of course, one of their followers—a devoted one, even, in my own fucked little way.

I tell myself I’m saving Poppy from something, keeping her from a failure that could break her.

Then she looks at me. “It’s like: do I try to stop feeling?”

But the thing is that when something’s dead, you can’t say anything about it that’ll bring it back.

I know exactly how it got past me: I don’t pay attention.

I’m so embarrassed I go back to bed.

She wants to prove that she is good, attentive, committed. I wonder why I can never harness this energy in myself; why I always want to do the wrong thing even when I don’t want to.

“Well,” he says, “you’re not a baby.” “And I never will be again,” I say, and then I’m aware of very little.

Then I move to the couch, where I lie down and look out the window and think about what it means that I’m a pleaser, and about how Poppy can just articulate something about me so clearly when I’ve never even glimpsed that something in myself, and moreover about how I can start working very hard to stop people-pleasing entirely in the months and years to come.

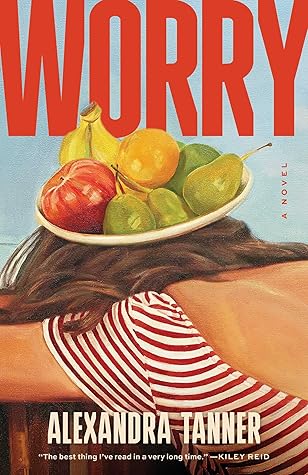

“Do you want a pear?” Poppy asks me, and the question seems loaded. I shrug. “Will you or will you not eat a pear in the next three to four days?” she tries again.

It’s the ease of my childhood I want back, not these shorts.

I wonder why I ever come outside.

I told myself I wouldn’t look at my phone while I was in the park, but I feel the only thing that will stop me from plummeting into sadness is to look at my phone.

“Is it a crisis you’ve made up in your head because you have no real crisis in your life?” Poppy asks.

Why does every message I send make me sound completely devoid of personality, perspective, intelligence?

I will look back on this one day as a moment in which I inched myself one step closer to total loneliness: to exactly what I was afraid of the whole time.

I wait until dark, then pour cold red sauce over linguine and turn on the pilot of Lost, which I’ve seen about eight times.

The part of my brain that loves hateful things is aglow.

I told him that my hating my mother and his hating my mother weren’t the same thing, and that they were ultimately irreconcilable, and he bought it.

She looks the way I’ve been trying to look for years.