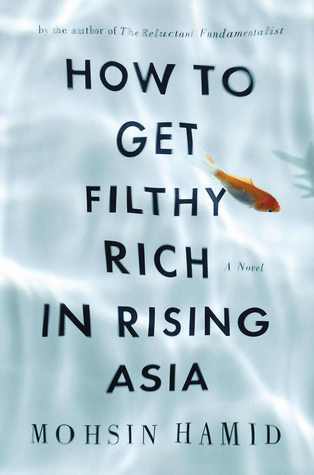

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Mohsin Hamid

Read between

September 26 - September 30, 2022

But when you read a book, what you see are black squiggles on pulped wood or, increasingly, dark pixels on a pale screen. To transform these icons into characters and events, you must imagine. And when you imagine, you create. It’s in being read that a book becomes a book, and in each of a million different readings a book becomes one of a million different books, just as an egg becomes one of potentially a million different people when it’s approached by a hard-swimming and frisky school of sperm.

You watch one after another of the ubiquitous, hyper-argumentative talk shows that fill your television, aware that in their fury they make politics a game, diverting public attention rather than focusing it. But that suits you perfectly. Diversion is, after all, what you seek.

You might therefore assume that the most reliable path to becoming filthy rich is to activate your faster-than-light marketing drive and leap into business nebulas as remote as possible from the state’s imperial economic grip. But you would be wrong. Entrepreneurship in the barbaric wastes furthest from state power is a fraught endeavor, a constant battle, a case of kill or be killed, with little guarantee of success.

Yet you have changed with the growth of your son. Medicalized, bloody, and enacted to the sound of screaming and the smell of disinfectant, his birth was like a death. It shook you. And, slowly, it unlocked forgotten capacities for feeling. Fatherhood has taught you the lesson that, even in middle age, love is practicable. It is possible to adore those newly come into your world, to envision, no matter how late in the day, a happily entwined future with those who have not been part of your past.

What we do know is that information is power. And so information has become central to war, that most naked of our means by which power is sought.

your son has chosen not to return after studying in North America, which, despite Asia’s rise, retains some attraction for a young conceptual artist with craggy hip bones and lips like buttered honey.

We are all refugees from our childhoods. And so we turn, among other things, to stories. To write a story, to read a story, is to be a refugee from the state of refugees. Writers and readers seek a solution to the problem that time passes, that those who have gone are gone and those who will go, which is to say every one of us, will go. For there was a moment when anything was possible. And there will be a moment when nothing is possible. But in between we can create.