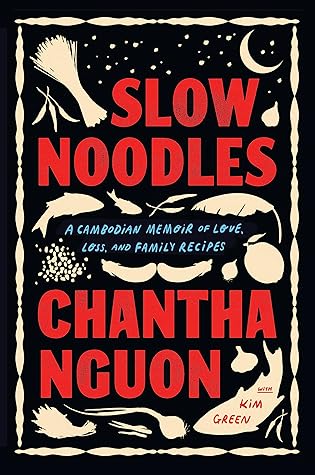

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

December 5 - December 19, 2024

To talk about pain is to lose face.

Lon Nol’s campaign to rid the nation of Vietnamese Communists quickly mutated into a sort of holy crusade against anyone of Vietnamese descent living in Cambodia.

Lon Nol’s violence, and his obsession with racial “purity” and restoring a glorious Angkorian past, augured tyranny and genocide. But as it turned out, he had these tendencies in common with the man who would soon overthrow him: Pol Pot, his Marxist mirror image. And in 1975, after five years of fighting, Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge would win the Cambodian civil war and launch a genocide so horrific and vast in scale that Lon Nol would become a historical footnote.

We have a saying in Khmer: “If a father dies, the children eat rice with fish. If a mother dies, the children sleep on a leaf.” It means that when you lose your mother, you lose everything. She is the roof over your head and the rice in your bowl. She is your strength.

In a practical sense, Chan and I had been living as husband and wife for months, so we registered as a couple. We had never discussed love or marriage. There was no room in our lives for romance. We had simply thrown in our lot with each other and faced our troubles together.

So I wonder, without answer, which one is a greater strength: feeling too much, or allowing yourself no feeling at all?

Beneath the headline, Charity Gets Tired, was a story about how dispiriting it was to pour support into refugee camps for years, as the ocean of need only deepened.

There are more than a thousand varieties of morning glory; this edible one, so beloved by Cambodians, is Ipomoea aquatica, a floating vine that goes by many aliases: water spinach, kangkong, ong choy, swamp cabbage, and water convolvulus, to name a few.

My son, Johan, rolls his eyes at my refrigerator, stuffed with ancient leftovers I can’t throw away. “You’re not starving anymore,” he says, worried for me. On the outside, I wear a mask of reassurance. But inside, I cannot relax my vigilance: I know that hunger can always return. Luck can run out anytime, so I always have a plan. Is this PTSD? Or is it déjà vu, paired with practical action? The answer is yes.