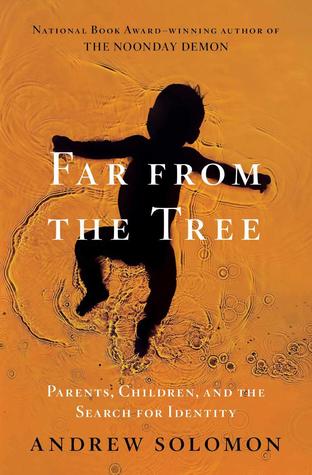

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

January 26 - February 26, 2025

Having anticipated the onward march of our selfish genes, many of us are unprepared for children who present unfamiliar needs.

Parenthood abruptly catapults us into a permanent relationship with a stranger, and the more alien the stranger, the stronger the whiff of negativity. We depend on the guarantee in our children’s faces that we will not die. Children whose defining quality annihilates that fantasy of immortality are a particular insult; we must love them for themselves, and not for the best of ourselves in them, and that is a great deal harder to do. Loving our own children is an exercise for the imagination.

Though many of us take pride in how different we are from our parents, we are endlessly sad at how different our children are from us.

Many parents experience their child’s horizontal identity as an affront.

Vertical identities are usually respected as identities; horizontal ones are often treated as flaws.

We often use illness to disparage a way of being, and identity to validate that same way of being.

I wanted to stop merely observing the wide

world and inhabit its wideness:

I am now wedded to the idea that without my struggles, I would not be myself, and that I like being myself better than I like the idea of being someone else—someone I have neither the ability to imagine nor the option of being.

modernity comforts us with trivial uniformities even as it allows us to become more far-flung in our desires and our ways of realizing them.

“You gotta take your mess and find yourself a message!”

Erving Goffman argues that identity is formed when people assert pride in the thing that made them marginal, enabling them to achieve personal authenticity and political credibility.

The able-bodied can be generous narcissists: they eagerly bestow what they feel good about giving without considering how it will be received.

Illiteracy and poverty are disabilities, and so are stupidity, obesity, and boringness.

Jim Sinclair, an intersex autistic person, wrote, “When parents say, ‘I wish my child did not have autism,’ what they’re really saying is, ‘I wish the autistic child I have did not exist, and I had a different (non-autistic) child instead.’ Read that again. This is what we hear when you mourn over our existence. This is what we hear when you pray for a cure. This is what we know, when you tell us of your fondest hopes and dreams for us: that your greatest wish is that one day we will cease to be, and strangers you can love will move in behind our faces.”

“When one is different, when what you are has the ability to determine who you are, there is an urge to resist.”

The tension between identity and illness is common to most of the conditions in this book, but in no other instance is the conflict so extreme. Confronting desperately frustrated parents with the idea that autism is not an adversity can seem insulting.

Why does Cece have autism? Because Cece has autism. And what is it like to be Cece? Being Cece. Because no one else is, and we’ll never know what it’s like. It is what it is. It’s not anything else. And maybe you’ll never change it, and maybe you should stop trying.”

Uta Frith of University College, London, has theorized that people with autism lack the drive for central coherence that allows humans to organize and learn from outside information.

God has many different ways to build a brain. A Cray supercomputer is used for really complex, intense computing that involves the manipulation of massive amounts of data. It runs so hot it has to be kept in a liquid cooling bath. It requires a very specific kind of TLC. And is the Cray defective because it requires this kind of nurturing environment for its functioning? No! It kicks ass! That’s what my kid is like. He needs support, needs attention, and is amazing.”

It is not possible to separate the autism from the person—and if it were possible, the person you’d have left would not be the same person you started with.”

Autistic people are valuable as they are. They don’t have value only if they can be transformed into less obviously autistic people.”

“His world has plateaued at the smallness that it’s at,” she

Asinine people gamely

produce asinine children even though stupidity makes life terribly hard;

Those who are prepared to love children with horizontal qualities give dignity to them, whether or not they have used prenatal testing.

Educating people on the challenges their children may embody is sensible, but preventing them from having children because we think we know the value of those lives smacks of fascism.

We may not be ashamed enough of what is authentically reprehensible, but we are likewise increasingly unashamed of what never should have discomfited us in the first place. The opposite of identity politics is embarrassment.

Lali’s parents believed that their love and tolerance defined their daughter, when those qualities really only defined them as loving parents. When broad-mindedness blinds us to our offspring’s needs, our love becomes denial. Acknowledging difference need not threaten love; indeed, it can enrich it.

would propose that only by allowing people born with horizontal identities not to change does one allow them to get better. Any of us can be a better version of himself, but none of us can be someone else.

courage to be extraordinary, and more confidence about being ordinary,

being anomalous does not deprive anyone of the right or ability to be typical.

I think all love is one-third projection and one-third acceptance and never more than one-third knowledge and insight.