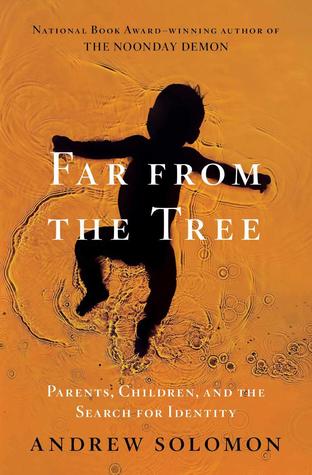

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Started reading

February 1, 2025

Parenthood abruptly catapults us into a permanent relationship with a stranger, and the more alien the stranger, the stronger the whiff of negativity. We depend on the guarantee in our children’s faces that we will not die. Children whose defining quality annihilates that fantasy of immortality are a particular insult; we must love them for themselves, and not for the best of ourselves in them, and that is a great deal harder to do.

Labeling a child’s mind as diseased—whether with autism, intellectual disabilities, or transgenderism—may reflect the discomfort that mind gives parents more than any discomfort it causes their child. Much gets corrected that might better have been left alone.

Such parents tend to view aberrance as illness until habituation and love enable them to cope with their odd new reality—often by introducing the language of identity. Intimacy with difference fosters its accommodation.

Treating an identity as an illness invites real illness to make a braver stand.

“If you bring forth what is within you, what is within you will save you. If you do not bring forth what is within you, what is within you will destroy you.”

Our parents are metaphors for ourselves: we struggle for their acceptance as a displaced way of struggling to accept ourselves. The culture is likewise a metaphor for our parents: our quest for high esteem in the larger world is only a sophisticated manifestation of our primal wish for parental love. The triangulation can be dizzying.