More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

February 5 - February 9, 2024

By the early twentieth century in Baltimore, it became illegal for a white person to move onto a street that was more than 50 percent Black and illegal for a Black person to move onto a street that was more than 50 percent white. That ordinance was the first of its kind in the nation, cementing apartheid in Baltimore and inspiring other Southern states to follow suit.

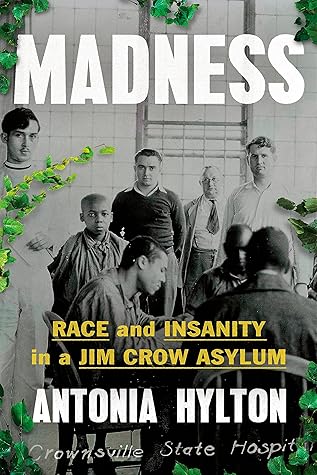

Maryland’s Hospital for the Negro Insane, later renamed Crownsville, took three seasons to build.

“Drapetomania,” he asserted, was the irrational and unnatural desire of a slave seeking freedom. If slaves didn’t have white people to take care of them, they would regress. He believed that enslaved people who misbehaved and ran away from their owners would develop drapetomania, and that slave owners who treated the enslaved with too much kindness could trigger it.

The possibility that physical abuse, forced labor, and being owned by another human might produce mental trauma was not of scientific concern.

Maryland’s Eastern Shore—the birthplace of Frederick Douglass—was home to breeding farms, where owners forced their slaves to reproduce children for sale across the South.

It would be the first and only asylum in the state, and likely the nation, to force its patients to build their own hospital from the ground up. Black Marylanders would have to earn their access to healthcare through hard labor and a return to the antebellum social order.

What does it mean to be healthy and well enough to clear the woods, build a road, and construct a hospital, yet also be so sick you require institutionalization? How do we decide who’s irredeemable and who’s capable of recovery? What role have men like Robert Winterode played in alienating Black patients from therapy and care?

Prior to the Civil War, Maryland had more free African American citizens than any other state—

In 1949, there were 1,800 patients and 392 staff members. Just five of those employees were Black. By 1956, there were 2,300 patients and 745 staff members, 326 of them Black.

So in 1953, when the National Mental Health Association asked asylums around the country to mail in any shackles or chains they’d previously used, Maryland leaders were eager to take part. It was a public declaration that restraint, fear, and incarceration would have no place in mental hospitals. On April 13 of that year, socialites and politicians, including Governor Theodore McKeldin of Maryland, convened at the McShane Bell Foundry in Baltimore. Together they melted down all of the chains and restraints received during the campaign and turned them into a 300-pound Mental Health Bell.

Around 1963, Crownsville—like all publicly run facilities—became required by law to admit patients of all races, pushing the patient population toward the kind of demographic changes seen among the staff. Between December 1962 and December 1967, Crownsville’s patient population went from being entirely nonwhite to approximately 70 percent Black.

He had become the mentee of a famous Black doctor by the name of Aris T. Allen, the same doctor who helped Gertrude deliver Faye into the world in 1953. For years, Allen had operated as one of only three Black physicians in Annapolis. Dr. Allen would go door-to-door, serving Black families who, prior to the 1960s, were not allowed inside the Annapolis Medical Center. He had been Dr. Sims’s personal pediatrician and later became the first African American to run for statewide office in Maryland and to chair the Republican Party.

In 1952, less than 150 per 100,000 people were incarcerated in state and federal prisons, while over 600 per 100,000 were living in some form of asylum.