More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

February 15 - March 2, 2025

The possibility that physical abuse, forced labor, and being owned by another human might produce mental trauma was not of scientific concern.

It would be the first and only asylum in the state, and likely the nation, to force its patients to build their own hospital from the ground up. Black Marylanders would have to earn their access to healthcare through hard labor and a return to the antebellum social order.

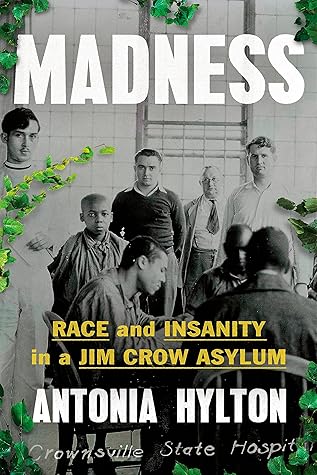

Early records and photos of Crownsville’s founding led me to question America’s legacy of race in mental health: What does it mean to be healthy and well enough to clear the woods, build a road, and construct a hospital, yet also be so sick you require institutionalization? How do we decide who’s irredeemable and who’s capable of recovery? What role have men like Robert Winterode played in alienating Black patients from therapy and care?

Whether doing laundry, weaving baskets, cooking, or transporting other patients, Crownsville patients were constantly offsetting the costs of their own care.

Patient stays were extended to meet production needs. Patients at Crownsville were trapped in a cycle of free labor—one that began as a questionable form of therapy and frequently ended either in their exploitation by local companies seeking a cheap labor source, or in their peonage and service to the very hospital and state that was intended to earnestly facilitate their rehabilitation.

Patient labor was often called industrial therapy, and it was popular in virtually every American mental hospital in the first half of the twentieth century.

The function of lynching was so much more than a bypassing of the justice system. It was a form of psychological terrorism. And it sent several messages. One basic message was that they had killed people like Williams and Armwood before and, if necessary, would do it again.

But the more subtle and crucial message was that they still owned Black people.

“The hospitals were breeding mental illness faster than they were curing it.”

Paul was drawn to the work of Dr. Thomas Szasz, a psychiatrist who forcefully argued that diagnoses were distractions from the root causes of why people are unwell.

Crownsville became increasingly isolated, and its isolation took on many forms. At its most literal, it was “cage” seclusion cells and labor that provided neither social contact nor vocational opportunity. At its most structural, it was part of a statewide effort to maintain separation of the races at any cost.

Almost two decades later, after years of observing my own family, I’ve grown convinced that when you swallow your pain it never does digest.

Was there a connection between the two: between living with the weight of that reality—striving to become somebody and to live defiantly in spite of it—and suffering mental trauma?

During this period, many Black families in Maryland believed that mainstream, majority-white newspapers like the Baltimore Sun made selective decisions to emphasize crime, dysfunction, and negativity in communities of color in the state.

White residents were advocating for the creation of a literal wall to keep Black patients at a distance.

We have fought hard and long for integration, as I believe we should have, and I know we will win, but I have come to believe that we are integrating into a burning house. —Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., as told to Harry Belafonte

At the time, syphilis was spreading within many poor Black communities. The disease had become heavily stigmatized, and even after the advent of penicillin, white doctors often refused to give Black people suffering with syphilis proper healthcare.

Former Crownsville employees and even relatives of local law enforcement officers have repeatedly described how they received money in exchange for bringing people to the hospital.

For the “crime” of frightening a white woman on a road, this woman spent years at Crownsville. That was all Joyce could see in documents about her psychiatric history.

Then, Donald realized that a lot of the patients he met were admitted only because county jails were too full.

Over the years, Crownsville had developed into a dumping ground—a place that seemed to swallow the undesired, poor, and nonconforming Black residents of Maryland and, at times, deny them fundamental human rights.

They were human, and the longer they worked there, the more often they found themselves in situations that forced them to ask the same questions over and over again. Is it worth it, doing incremental good in an imperfect system? Can you be a good person and work somewhere where something like this happens?

this Great Migration was not a careful and calculated choice—it was terrorism. It was a sudden expulsion. And as much as it had the power to lift Black families up, the journey north had the power to break them down.

At the end of the nineteenth century, steel mills often used formerly enslaved people as strikebreakers against white union employees—a move that not only undermined the union’s bargaining efforts but also intentionally fostered racial animus and suspicion.

Crownsville had become a weapon against those who dared oppose the existing order.

an early sign that some white leaders and doctors would, wittingly or unwittingly, misread Black anger as mental illness and use tools of psychiatry to punish, not to heal, the communities they were meant to serve.

“people are made into healthy humans by their interaction with a competent social environment” and not in institutions.

At a time when the hospital was supposed to be focused on discharging patients and prioritizing bonds with families and communities, Crownsville was still an appendage to Maryland law enforcement, mediated by officers and judges who actively collaborated in a process that seemed to care little for distinctions like those between “mental illness” and “criminality.”

while African Americans made up just over 10 percent of the general population in 1965, they suffered 24 percent of the U.S. Army’s fatal casualties. Among Black soldiers a paranoid theory emerged: perhaps they were putting us on the front lines for genocidal purposes.

As sociologist James M. Fendrich put it: Black Vietnam veterans came back to America and had to face “the transition from ‘democracy in the foxhole’ to discrimination in the ghetto at home.” Their anger and alienation from American society was simmering, not dissipating. The military, as it turned out, was ahead of most large American institutions in its pace and willingness to integrate.

It appeared Crownsville’s patients were not only receiving less care, but when they did get support, they were more likely to have contact with people adjacent to the criminal justice system than the kinds of professionals who would have welcomed them back into jobs and school—the fundamental pillars that form community.

exhibited to each other,” he told me. The long history of the asylum system seemed to be weighing on him. “By the time I entered,” he explained, “chains had been replaced by drugs. So the chains were still there.”

In 1957, Baltimore’s Clifton Park Junior High School had 2,023 white students and thirty-four Black students. One decade later, the same school had 2,037 Black students and twelve white students. Middle- and upper-middle-class white families abandoned the city’s public schools in shocking numbers. They fled to the suburbs in thousands, and many of those suburban voters stopped voting for welfare and social programs.

When temperatures would plummet in December, employees knew to make preparations for a group of patients who did not have any mental health diagnoses: homeless men and women of all racial backgrounds who would voluntarily commit themselves to Crownsville.

As the patient became the inmate, the hospital’s story raised the question: what was the difference between deeming Black populations irredeemable or incurable?

As the state’s psychiatric facilities slowly declined, the prisons accepted a record load.

By the 1990s, the United States reached a rate of opening one new prison or jail every single week to accommodate its growing carceral population.

Is it a coincidence that at the very historical moment when the asylum was being dismantled, the prison, which had collaborated and exchanged extensively with hospitals like Crownsville, rose to prominence?

Dr. Benton believes the best way forward is to train a generation of healthcare providers in “cultural humility,” or, in other words, the strength to acknowledge the limits of what they know and to remain open to asking new questions.

It was a reminder to me that the complexity and mystery of mental illness are no excuse to not take action, push for change, or find small ways to help the people around us. Perhaps that is part of what makes us so unsettled when we encounter others who can’t conceal how sick, lost, and distraught they feel. We are confronted with a choice—when what we really want to do is to shirk responsibility. We are reminded that we are not so healthy and virtuous after all. We’re forced to consider the role we might have played in isolating our neighbors, and how crazy it was that we ever thought we

...more