More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

February 12 - February 19, 2025

The possibility that physical abuse, forced labor, and being owned by another human might produce mental trauma was not of scientific concern. Decades later, at the turn of the century in Maryland

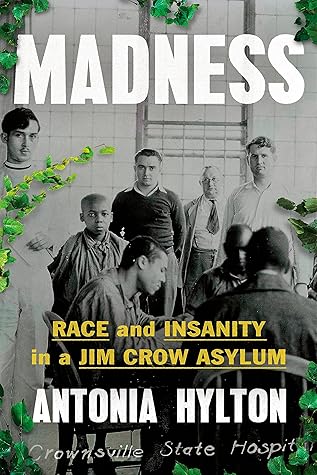

It would be the first and only asylum in the state, and likely the nation, to force its patients to build their own hospital from the ground up. Black Marylanders would have to earn their access to healthcare through hard labor and a return to the antebellum social order.

Once construction was complete, Winterode was proud of what he had helped birth: Crownsville Hospital was standing tall, the product of its future patients. A place that conveniently became both a solution to white Marylanders’ concerns and a pen for the Black people who’d just built it.

What does it mean to be healthy and well enough to clear the woods, build a road, and construct a hospital, yet also be so sick you require institutionalization? How do we decide who’s irredeemable and who’s capable of recovery? What role have men like Robert Winterode played in alienating Black patients from therapy and care?

A cop killed Maynard. Nobody in the family had witnessed his cousin’s final moments, so everything we knew about Maynard’s killing came from the Mobile, Alabama, police department. Everything I was going to know about Maynard came from the white police officer who shot him within seconds of finding him.

Many of the changes they implemented cost the hospital little beyond a bit of energy and attention to detail. It seemed to Marie as though white staff didn’t care how exposed or humiliated the patients looked and felt.

White Marylanders were not only indifferent to the therapeutic circumstances for Crownsville patients, but preferred that the patients stay as far away as possible in a well-isolated establishment.

it was agonizing for them to watch the hospital become a facility for people the state had no plan to help and nowhere else to send. Even though they could recognize the greater social and systemic factors at fault, they couldn’t help but feel personally responsible.

“Segregation was expensive,” the article read, “and the people who suffer most when budgets are cut are the patients in the Jim Crow institution.”

Records and oral history show that some of the doctors, directors, and staff at Crownsville, and much of the state leadership responsible for the hospital’s funding and care, directly and knowingly harmed patients. They also show that the dysfunction and stigma associated with the hospital made it easier for them to carry out this harm.

Many of the people of Crownsville decided that it was better to throw as many starfish back into the ocean as they could rather than abandon them all on the shore.

“The great 1950s push for research in mental hospitals involved numerous human rights violations,” Paul wrote to me. At the time he arrived in the 1960s, staff were sometimes still offering patients cigarettes and candies in exchange for trying out new drugs. “P.S.” he added, “I am not making any excuses for Crownsville staff. They, after all, referred the patients for the research studies.”

Care for the long-term mentally ill, of all races, was brutal.

In most states they don’t send sane people to mental hospitals, but here in the highly civilized state of Maryland, anything is liable to happen… In some sections of Maryland… white folks seem to think that when colored folks don’t act like they (the white folks) think they should act, then the colored folks are crazy.

All the Elkton Three did was pull off Route 40 to buy a meal. Their resistance was nothing more than seeking rest and basic human treatment. But they had crossed both physical and invisible color lines, and the punishment for that in the South was not just public shame—it was a portrait of insanity. Crownsville had become a weapon against those who dared oppose the existing order.

To put it simply: Black Americans refused to quiet their pain or to live as second-class citizens any longer.

“You know, I tried to talk about good roads and good schools and all these things that have been part of my career, and nobody listened. And then I began talking about niggers, and they stomped the floor.”

The Civil Rights Movement made criminality a disproportionately prevalent and racialized issue, setting in motion a pattern of events that stretched the definition of criminal behavior and strengthened every part of the carceral apparatus. Asylums included.

“By the time I entered,” he explained, “chains had been replaced by drugs. So the chains were still there.”

The story of America’s mass incarceration and prison expansion often goes as follows: mid-century deindustrialization shatters economic opportunity in inner cities, minority communities turn to the illicit economy for work, mainstream white America fears gangbangers and crack babies and tires of the welfare state. The United States government takes a tough-on-crime stance, instituting new drug and mandatory minimum sentencing laws that disproportionately affect Black communities and lead to an influx of young Black men into overcrowded prisons. This is a powerful and thorough narrative, but it

...more

it is no coincidence that the end of the twentieth century marks both the decline of the mental hospital and the expansion of the prison system.

Even when prisons weren’t replacing asylums, they were drawing inspiration from them. “Rehabilitation” programs and interventions focused on youth deviant behavior became a way for prisons to expand and interact with new populations. They began to copy the programs that were once found only in mental hospitals.

For most of the twentieth century, state mental hospital patients were majority middle-aged and white, and our modern incarcerated populations are now predominantly young and nonwhite. It is precisely the fact that our incarcerated populations look closer to Crownsville’s demographics that led me and other journalists and historians to raise questions about who benefited from deinstitutionalization and who did not. Is it a coincidence that at the very historical moment when the asylum was being dismantled, the prison, which had collaborated and exchanged extensively with hospitals like

...more

But Maryland’s governor Wes Moore acknowledged that we have too many people with behavioral health challenges behind bars, and that “it’s hard to quantify all of the ways in which America’s history of racism and segregation continues to harm our communities.” He had made his own inferences as a Black kid in 1982, when his father died from a rare but treatable virus called acute epiglottitis. “I know firsthand what happens when people are treated differently in our medical system,” he told me. “I watched my father die when I was just three years old because he didn’t receive the treatment that

...more

the truth is we seem to have reached the limit of what people are willing to accept in their communities. Everyone says, ‘Community mental health centers are great’—as long as they are in somebody else’s community.”

In only half a century, the United States achieved arguably the greatest and swiftest institutional shift in history, at once making the mental hospital redundant and law enforcement and incarceration of astonishing prevalence.

He envisions a world in which schools would train future psychiatrists and psychologists to give patients agency and control in their care. They should stop preaching to patients about what they should do or how they should feel, and instead ask patients questions like, “How do you want to feel?” He hopes providers will partner with their patients during the development of the initial treatment plan and be open about the fact they’re going to need some backup plans for inevitable failures. Failure, relapse, and setbacks are all part of being human. He wants them to know it’s okay to explore

...more

“Mental health can only be helped with hope and healing of the soul.