More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

April 6 - April 22, 2024

Social workers, family physicians, and teachers have all reported growing concern about the crisis of mental health in the United States. According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, an estimated one in five adults and one in six children in our country experience mental illness in a given year. Depression, suicidal ideation, and drug overdose stats have accelerated. At the same time, many mental health services and therapists are not covered by Medicaid and public insurance.

“There’s an assumption,” she told me, “that when a Black kid comes to the emergency department, the problem is behavioral. It’s not depression.”

The conditions of his segregated confinement at the hospital had been justified by white politicians and doctors as necessary, fueled by a century-long belief that newfound freedom had increased the rates of insanity among Black people.

William was lowered into the ground at Laurel Cemetery, the first non-faith-based cemetery for Baltimore’s Black community. Laid to rest among Union soldiers, businesspeople, and civil rights activists, William had made his way home to peace for the first time in years. Prejudice and racial violence had surrounded him—it had determined where he lived, how he taught his students, and how hard he had to work to advance his family. His downfall, his broken spirit, and his stolen life were the residue of the racial lines that had formed and collapsed around him. It was a bondage to these color

...more

Swiskowski was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to ten years in prison for the lethal assault of William H. Murray. His defense attorney, Milton Dashiell, was a prominent segregationist and the very same man who had drafted Baltimore’s infamous apartheid ordinance of 1910. The city’s second segregation ordinance would be drafted by a man named William L. Marbury. Marbury would later head the board of managers of Crownsville Hospital.

As an adult, Pauli Murray came across a sociological study, Social and Mental Traits of the Negro, that had been published in 1910, the same fateful and charged year in which she had been born. In it, a white sociologist named Howard W. Odum argued that “the migratory or roving tendency seems to be a natural one to [Black people], perhaps the outcome of an easy-going indolence seeking freedom to indulge itself and seeking to avoid all circumstances which would tend to restrict its freedom.” Odum believed that a Black person’s desire for autonomy and mobility was the byproduct of a

...more

In the view of many prominent physicians at the time, the end of slavery had created a kind of aimless vagrant who needed to be concealed and incarcerated in a new form of institution.

Cartwright, a physician and professor at the University of Louisiana, wrote about his pseudoscientific beliefs and observations of African slaves. “Drapetomania,” he asserted, was the irrational and unnatural desire of a slave seeking freedom. If slaves didn’t have white people to take care of them, they would regress. He believed that enslaved people who misbehaved and ran away from their owners would develop drapetomania, and that slave owners who treated the enslaved with too much kindness could trigger it.

The possibility that physical abuse, forced labor, and being owned by another human might produce mental trauma was not of scientific concern.

Maryland’s Eastern Shore—the birthplace of Frederick Douglass—was home to breeding farms, where owners forced their slaves to reproduce children for sale across the South.

For decades, they would be more likely to die there than find their way home.

The laborers who had toiled over the grounds were marched inside the buildings, into rooms they had hammered into place, and admitted as the very first patients. But that would not mark the end of their days of work. In addition to planting and harvesting crops on the Crownsville campus, the patients “were taken in motor trucks to adjoining farms within a radius of ten miles,” where they “gathered the crops for the farmers who were without help.” The twenty-eighth Lunacy Commission report boasted about how useful it was to have a captive work force that they could send about town. “This is

...more

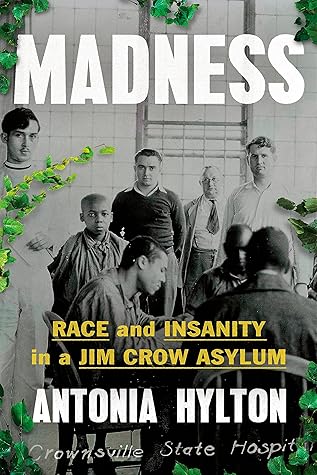

Crownsville’s origin established patterns that would haunt the asylum for its ninety-three years in operation. Early records and photos of Crownsville’s founding led me to question America’s legacy of race in mental health: What does it mean to be healthy and well enough to clear the woods, build a road, and construct a hospital, yet also be so sick you require institutionalization? How do we decide who’s irredeemable and who’s capabl...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

There to serve the more than five hundred patients at the time were two physicians and seventeen nurses. That year, twenty-eight patients were discharged as improved, eleven more were sent home despite a lack of improvement, and a shocking ninety-seven people died.

Patient stays were extended to meet production needs.

Continued indentured servitude was something of an open secret, and not just on the Eastern Shore. In 1927 a grand jury report found that an institute called the House of Reformation for Colored Boys in southern Maryland was forcing young Black boys to work on local farms and in businesses like broom factories. The school was intended to “instruct” and “reform” boys who had been labeled as vicious and improper, and many of the boys housed there were known to be “mentally deficient.” The investigators found that the boys were being farmed out in direct competition with regular laborers, and

...more

The Eastern Shore fought aggressively to maintain this kind of system—and for decades after slavery’s end, Black people continued to serve as the cheap labor source on the region’s farms. As a result, Black families lived in desperate poverty, and they would sometimes give away their children, especially those with developmental disabilities, to white families looking for a laborer or maid. These children effectively became slaves again.

“If you must take him, do it quietly.”

They tied an unconscious Williams by the neck and began to lift him up, then drop him down. Over and over again. The mob allowed Williams to hang lifelessly for twenty minutes, as they mocked the victim and took parts of his anatomy as souvenirs.

The mob removed Williams’s fingers and toes and threw them on the porches of Black homes, shouting that they should make nigger sandwiches.

The function of lynching was so much more than a bypassing of the justice system. It was a form of psychological terrorism. And it sent several messages. One basic message was that they had killed people like Williams and Armwood before and, if necessary, would do it again. But the more subtle and crucial message was that they still owned Black people. That they could sever their body parts, and continue to have complete and utter dominion. They controlled their livelihoods and their prospects. They could take ownership of people seen as destitute, different, and strange. They also owned the

...more

But how do you deal with The Man?” Kendal once asked me earnestly. I fell silent. “People were out to get him, and eventually people got him. It is hard to identify or diagnose mental illness in those conditions. It makes the symptoms look logical.”

Often, the media emphasized stories of escapes and riots at Crownsville, and subtle differences in word choice suggested that while residents may have expected the institution to manage aggressive Black patients, they anticipated the rehabilitation of white patients.

He referred to Crownsville patients’ actions as an “escape,” while describing the white patients as simply “leaving without permission.”

For years, white residents had been the first to criticize Crownsville as a failure and a local threat. But when time came to take action on those failures and to find these children a safe, better-funded alternative, these same communities wanted those patients to believe things weren’t bad enough to warrant help.

U.S.-backed dictator, military sergeant, and former president Fulgencio Batista refused to lose an election and installed himself as the nation’s leader once again. This time, he came back ruthless. He crushed, tortured, and jailed his enemies, censored the schools and the press, and allowed for rampant privatization and de facto segregation to disenfranchise Afro-Cubans en masse. In the background of the death and the violence, Havana was becoming a playground for the corrupt, as Batista made the city a safe haven for the American mob in exchange for a cut of their profits.

Estela coped by telling herself a story about America that was not true, either. She liked to tell herself that this country was better and more peaceful than being in Cuba because that simplified version of the story soothed her. It eased heartache. It made it easier to leave her hurting family and country behind. But the people who knew her saw the moments when her story would crack, and Estela would become irritable and lash out. She was lonely. I learned so much about storytelling from my grandmother—about how people engage in mythmaking to survive.

Maryland was one of the twenty-nine U.S. states that banned interracial marriage and cohabitation. As their relationship progressed, the obstacles piled up. There were countless restaurants where they couldn’t eat together, theaters where they couldn’t sit together, shops they couldn’t safely enter. They were harassed, yelled at, and spit on when they linked arms or held hands together in Baltimore. It was humiliating and scary but Estela was too grown up to retreat behind the walls of a convent. The city she had loved, where she had found a chosen family and constructed a sense of self and

...more

A nurse wrote on my mother’s birth certificate that her father—a man completely incapable of getting a tan—was a “negro.” Nobody in the family ever asked the hospital why. My mom assumes she did it for Estela’s own good. It was another myth that kept my grandmother safe in Baltimore.

At the same time, a rumor spread rapidly across Anne Arundel County: there was a government-funded gas chamber installed on the grounds of Crownsville Hospital, and in the event of an atomic bomb, the state would exterminate its patients to make room for surviving victims. As frightening and unbelievable as those claims sounded, they were bought and spread far enough that the Washington Post got hold of them. In a story published on May 20, 1951, a reporter found the likely source of the rumor: a Crownsville nurse and first aid instructor named Charles F. Nash. Nash had allegedly been telling

...more

The behavior of Charles Nash, Mrs. Martin, and others involved in the rumor seemed to reflect the Cold War paranoia then sweeping the nation, and the ways in which the horrors of the world were bearing down on everyday people. It was a rumor, a lie with no basis in fact, allegedly perpetrated not by a patient but by a nurse. The lines between reality and imagination, and who was sane and who was insane, were thin. As silly as they seem, those rumors had the potential to cause real harm and to distract from the very real crises that patients at Crownsville had been rioting and crying out for

...more

The supervisor had seen Bell hanging around looking lost in Baltimore one day. After speaking with him, he thought Bell sounded funny and was convinced he was using a fake accent. He put him in a car and brought him to the hospital. Marie said her supervisor childishly bragged about getting twenty-five dollars in cash for the patient delivery. Former Crownsville employees and even relatives of local law enforcement officers have repeatedly described how they received money in exchange for bringing people to the hospital. It’s part of what fueled the nightmares of Black Annapolitans, who used

...more

It sounded to her as though Mr. Bell had loitered around and had been stuck at Crownsville for the crime of being a Black man lost in the city with a foreign accent.

Before Crownsville, this patient had been living on the Eastern Shore. One afternoon, the woman stepped onto a busy road and startled a horse. The horse reared back and frightened its rider, a local white woman. For the “crime” of frightening a white woman on a road, this woman spent years at Crownsville.

In her work, she saw many patients picked up and brought to Crownsville under the guise of anti-vagrancy laws. Patients had gotten drunk in public or had slept on the street, and woke up at Crownsville.

Over the years, Crownsville had developed into a dumping ground—a place that seemed to swallow the undesired, poor, and nonconforming Black residents of Maryland and, at times, deny them fundamental human rights.

According to hospital records from 1968, the patient population remained majority Black in large part because twice as many Black people were being admitted to the system as white people.

But as her mother’s cells were transformed into billion-dollar drugs and vaccines, Elsie was at Crownsville. The evidence suggests she was used by science, too.

Some of the earliest Black nurses felt their patients had been coerced into an electroshock routine. It wasn’t being used as a last resort; it had become as normal as taking vitamins in the morning. They worried that while these therapies were sometimes meant as genuine treatment—and some patients liked and requested them—there were teams at the hospital who seemed to leverage them as punishments.

As I got a little older, though, I found out from family—not from my schoolteachers—that many never wanted to leave at all. That they often had less than twenty-four hours to plan their departure, and the stakes were not this-job-or-that-job; they were sometimes life or death. For these families, this Great Migration was not a careful and calculated choice—it was terrorism. It was a sudden expulsion. And as much as it had the power to lift Black families up, the journey north had the power to break them down.

In some sections of Maryland… white folks seem to think that when colored folks don’t act like they (the white folks) think they should act, then the colored folks are crazy.

The Elkton Three were an example of this kind of infiltration, an early sign that some white leaders and doctors would, wittingly or unwittingly, misread Black anger as mental illness and use tools of psychiatry to punish, not to heal, the communities they were meant to serve.

Metzl found that clinicians started to depict Black mental patients as threatening and uncontrollable, while white patients with the same illness were described sympathetically as “withdrawn,” nonviolent, and compliant. Suddenly, the rates of schizophrenia among Black men skyrocketed, and the entire image of the disease changed. The title of Metzl’s book came from a 1968 piece in Archives of General Psychiatry, in which two psychiatrists redefined schizophrenia as “a protest psychosis” that involved Black patients who had become hostile, aggressive, and developed “delusional anti-whiteness”

...more

African Americans were placed in ground combat battalions in higher percentages than whites, and while African Americans made up just over 10 percent of the general population in 1965, they suffered 24 percent of the U.S. Army’s fatal casualties.

On February 25, 1967, Martin Luther King Jr. stood at a podium in Los Angeles and asked the nation to make a full accounting of the atrocities committed at home and abroad. “We see the rice fields of a small Asian country being trampled at will and burned at whim; we see grief-stricken mothers with crying babies clutched in their arms as they watch their little huts burst forth into flames; we see the fields and valleys of battle being painted with humankind’s blood; we see the broken bodies left prostrate in countless fields; we see young men being sent home half-men—physically handicapped

...more

Americans were growing angrier at the human cost of this war. But the chemical warfare—the eleven million gallons of mist that hung in the jungle, that burrowed into the soil and sunk under your skin—nobody had accounted for that yet.

But for the men exposed to this toxin, there was also an underlying change in their health. Sometimes their memory was shot—their thinking often completely illogical. Their nerves and impulses could be jumpy and unpredictable. It could feel like their limbs were numb, or worse, on fire. The man from Maryland continued to dress in combat clothes and heavy black boots, as though any minute now he was going to be shipped back to the jungle. Everyone had read the stories about the terrible mist he had helped spray all across Vietnam. Hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese people died from Agent

...more

They observed a society that was generally “repulsed” by patients, and which was actively engaging in restrictive zoning to prevent the construction of group homes in certain neighborhoods.

“By the time I entered,” he explained, “chains had been replaced by drugs. So the chains were still there.”

Although many white Americans accepted racial equality and integration in principle, demographic trends from the period suggest they felt differently in practice.