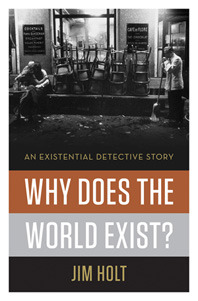

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Jim Holt

Read between

March 18 - March 31, 2020

The problem with the science option would seem to be this. The universe comprises everything that physically exists. A scientific explanation must involve some sort of physical cause. But any physical cause is by definition part of the universe to be explained. Thus any purely scientific explanation of the existence of the universe is doomed to be circular.

Leibniz called the Principle of Sufficient Reason. This principle says, in effect, that explanation goes all the way up and all the way down. For every truth, there must be a reason why it is so and not otherwise; and for every thing, there must be a reason for that thing’s existence.

The principle seems to inhere in reason itself, since any attempt to argue for or against it already presupposes its validity.

But it doesn’t follow that the existence of a given thing can be explained only by invoking other things. Maybe a reason for the world’s existence should be sought elsewhere, in the realm of such “un-things” as mathematical entities, objective values, logical laws, or Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle.

we can’t rule out the possibility that our own universe was created by someone in another universe who just felt like doing it.”

But what was the explanation for God’s own existence? Leibniz had an answer to this question too. Unlike the universe, which exists contingently, God is a necessary being. He contains within Himself the reason for His own existence. His nonexistence is logically impossible. Thus, no sooner was the question Why is there something rather than nothing? raised than it was dispatched. The universe exists because of God. And God exists because of God.

The Godhead alone, Leibniz declared, can furnish the ultimate resolution to the mystery of existence.

If you turn on your television and tune it between stations, about 10 percent of that black-and-white speckled static you see is caused by photons left over from the birth of the universe. What greater proof of the reality of the Big Bang—you can watch it on TV.

The life of the universe, like each of our lives, may be a mere interlude between two nothings.

TODAY, THINKERS REMAIN divided into three camps by the question Why is there something rather than nothing? The “optimists” hold that there has to be a reason for the world’s existence, and that we may well discover it. The “pessimists” believe that there might be a reason for the world’s existence, but that we’ll never know for sure—perhaps because we see too little of reality to be aware of the reason behind it, or because any such reason must lie beyond the intellectual limits of humans, which were tooled by nature for survival, not for penetrating the inner nature of the cosmos. Finally,

...more

God could not possibly stand apart from nature, he reasoned, because then each would limit the other’s being. So the world itself is divine: eternal, infinite, and the cause of its own existence.

“Anxiety reveals the Nothing,” he observed—his italics. Heidegger distinguished between fear, which has a definite object, and anxiety, a vague sense of not being at home in the world. What, in our anxious states, are we afraid of? Nothing! Our existence issues from the abyss of nothingness and ends in the nothingness of death. Thus the intellectual encounter each of us has with nothingness is suffused with the dread of our own impending nonbeing.

And there was no “coming into being”—at least not a temporal one. As Grünbaum is fond of saying, even though the universe is finite in age, it has always existed, if by “always” you mean at all instants of time.

Simple theories are obviously more convenient to use, more congenial to our intellects. They also appeal to our aesthetic sense. But why should they be more likely to be true than complex theories? This is a question that philosophers of science have never satisfactorily answered.

Yet it did not surprise Grünbaum. So what, he said, if the Null World has the greatest a priori probability? “Probabilities just do not legislate ontologically,” he kept insisting. Probability is not, in other words, a force driving the way reality should turn out, a force that had to be countered by another force, divine or otherwise, if there was to be Something rather than Nothing.

But is there anything truly paradoxical about an infinite past? Some thinkers object to the notion because it entails that an infinite series of tasks might have been completed before the present moment—which, they say, is impossible. But completing an infinite series of tasks is not impossible if you have an infinite amount of time in which to perform them all. In fact, it is mathematically possible to complete an infinite series of tasks in a finite amount of time, provided you perform them more and more quickly. Suppose

you can accomplish the first task in an hour; then the second task takes you a half hour; the third takes you a quarter of an hour; the fourth takes you an eighth of an hour; and so on. At that rate, you will have finished the infinite series of tasks in a total of just two hours. In fact, every time you walk across a room you accomplish such a miracle—since, as the ancient philosopher Zeno of Elea observed, the distance you cover can be divided into an infinite number of tinier and tinier intervals. So Kant and al-Ghazālī were wrong. There is nothing absurd about an infinite past. It is

...more

One traditional route is the cosmological argument for the existence of God.

The universe is contingent. It might not have existed. Given that it does exist, there must be an explanation for its existence. It must have been caused to exist by some other being. Suppose that this being, too, is contingent. Then it requires an explanation for its existence as well. And so on. Now, either the explanatory chain eventually comes to an end, or it does not. If it does come to an end, the last being in the chain must be self-explanatory. If it goes on ad infinitum, then the entire chain of beings stands in need of an explanation. It must have been caused by some being outside

...more

The ontological argument purports to establish God’s existence through logic alone. God must exist as a matter of logical necessity, it says, since he possesses all perfections, and it is more perfect to exist than not to exist.

The God it purports to deliver is a necessary being. His existence is a truth of pure logic, a tautology. But tautologies are empty propositions. Since they are true regardless of how reality is, they are devoid of explanatory content. How could such a tautological divinity be the fons et origo of the contingent world we see around us? How could a tautology exercise free will in creating it? The gap between necessity and contingency is no less difficult to bridge than the gap between being and nothingness.

If the existence of a world could be deduced from a logically necessary truth, then it too would be logically necessary. But it isn’t. Although there is a world, there might not have been. Nothingness cannot be dismissed as a logical possibility. Even the most promising attempt to derive being from pure logic—the ontological argument for the existence of God—in the end comes to nothing.

Suppose we take the laws of general relativity, which govern cosmic evolution on the largest scale, and extrapolate them backward in time toward the beginning of the universe. As we watch the evolution of our expanding and cooling cosmos in reverse, we would see its contents contracting and growing hotter. At t = 0—the moment of the Big Bang—the temperature, density, and curvature of the universe all go to infinity. Here the equations of relativity break down, become meaningless. We have reached a singularity, a boundary or edge to spacetime itself, a point at which all causal lines converge.

...more

But what is more interesting than what it forbids is what quantum theory permits. It permits particles to pop into existence spontaneously, if briefly, out of a vacuum. This scenario of creation ex nihilo led quantum cosmologists to entertain an arresting possibility: that the universe itself, through the laws of quantum mechanics, bounded into existence out of nothing. The reason there is Something rather than Nothing is, as they fancifully put it, that nothingness is unstable.

(“With or without religion, you would have good people doing good things and evil people doing evil things. But for good people to do evil things, that takes religion.”),

If the ultimate laws of physics, like Plato’s eternal and transcendent Forms, did have a reality of their own, that would only raise a new mystery—two mysteries, in fact. The first is the one that bothered Hawking. What gives these laws their ontic clout, their “fire”? How do they reach out and make a world? How do they force events to obey them? Even Plato needed a divine craftsman, a “demiurge,” to do the

actual work of fashioning the world according to the blueprint that the Forms provided. The second mystery that arises if the laws of physics have their own transcendent reality is even more basic: Why should those laws exist? Why not some other set of laws or, even simpler, no laws at all? If the laws of physics are Something, then they cannot explain why there is Something rather than Nothing, since they are a part of the Something to be explained.

But when physicists and philosophers talk about two different regions of spacetime being “two universes,” what they generally mean is that those regions are (1) very, very large; (2) causally isolated from each other; and hence (3) mutually unknowable by direct observation. The case for saying the two regions are separate universes is strengthened if (4) they have very different characters—if, for instance, one of them has three spatial dimensions whereas the other has seventeen dimensions. Finally—and here is the existentially titillating possibility—two regions of spacetime might be called

...more

Did Descartes here infer more than he was entitled to? As many commentators have pointed out (beginning with Georg Lichtenberg in the eighteenth century), the “I” in his ultimate premise is not quite legitimate. All Descartes could assert with certainty was “There are thoughts.” He never proved that thoughts require a thinker. Perhaps the pronoun “I” in his proof was just a misleading artifact of grammar, not a name for a genuinely existing thing.