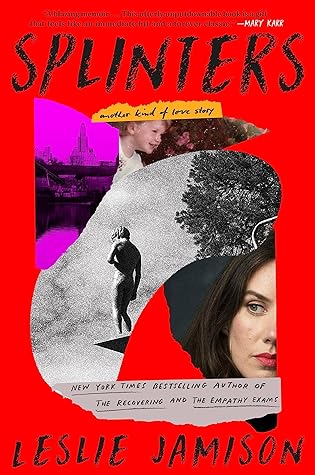

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Our sublet was long and dark. A friend called it our birth canal.

When I was very young, I thought divorce involved a ceremony: the couple moved backward through the choreography of their wedding, starting at the altar; unclasping their hands, and then walking separately down the aisle. I once asked a friend of my parents, “Did you have a nice divorce?”

Falling in love with C was encompassing, consuming, life-expanding. It was like ripping hunks from a loaf of fresh bread and stuffing them in my mouth.

The voice of the good student in me—the one who always needed to do what she was told, because otherwise maybe she wouldn’t be loved—

“If you ever find yourself in the wrong story, leave.” It didn’t say anything about who you left behind.

Then my therapist’s voice arrived, You can see the trailheads of these thoughts, but you don’t have to follow them.

The endlessness I’d felt in that roadside diner had seemed like a promise. Now I knew better. Almost every sense of endlessness had an ending.

My life was barely my own anymore; I shared custody of all my feelings with Spotify.

The older I got, the more I realized how little control I had over the stories other people were writing about their lives.

Pavlov knew that intermittent reinforcement was more powerful than giving the dogs a treat every day.

That was the surprise of it—not the ending, but the fact that something so predictable could hurt so much.

We aren’t loved in the ways we choose. We are loved in the ways we are loved.

she’d always believed that some love affairs were epic novels, while others were short stories. Some were just poems. One-night stands were haikus.

Trusting the stories I told myself about romance made me feel like a moth stubbornly ramming itself against a flickering bulb. The bulb would never be the moon.

it was no longer about building a life, but rebuilding one. Any version of this life would be built over the bones of what came before.

I was pleased by the generosity of this notion—that every single person was the most interesting person in the world, to someone.

It’s what the fairy tales have been trying to tell us for centuries. Don’t be afraid of never getting what you want. Be afraid of what you’ll do with it.

Didn’t everyone sometimes bore the people who loved them most? Wasn’t that ultimately a more sustainable notion of love, anyway—a love that wanted to involve all your tedious moments, rather than turn away from them?

This was one of the lessons I kept learning: the difference between the story of love and the texture of living it; between the story of motherhood and the texture of living it, the story of addiction and the texture of living it, the story of empathy and the texture of living it.

As it turned out, I was neither a villain nor a goddess, but just—as they say in recovery—a woman among women, a person among people. No better or worse than the rest.

My love for our daughter would always hold the vows I’d broken, alongside the versions of our life I’d dreamed, and then buried, and then grieved.

Those families on the beach were a reminder of what I’d chosen to break. But I knew this would happen no matter how I lived: I’d spot the impossible ideal somewhere else.

To stop fetishizing the delusion of a pure feeling, or a love unpolluted by damage. To commit to the compromised version instead.

True love wasn’t a delusion I needed to give away like an impractical, too-tight cocktail dress.