More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Lucy Worsley

Read between

November 25, 2023 - January 9, 2024

What else have I learned from writing this history of domestic life? It’s been brought home to me that biology has always been destiny. Many major social upheavals come back, in the end, to little changes in the way that people think about and look after their bodies. I also think it’s interesting and instructive to find that the put-upon and down-and-out in the past weren’t always worse off than they are today.

My conclusion is that we have some distance yet to travel on this journey towards the good life, but that history can help to show us the way.

Society was structured so that one’s position in the hierarchy was obvious and explicit. There was a ‘Great Chain of Being’ extending down from God, through his angels, to the Archbishop of Canterbury and other notables such as dukes, before normal people got a look-in. But at least we lesser mortals could take comfort from being placed above the animals, the plants, and finally, the stones. Such a chain inevitably restricted people’s hopes of bettering their social position, but it also comforted them. Those higher up adopted airs of superiority, but they also had clear and pressing

...more

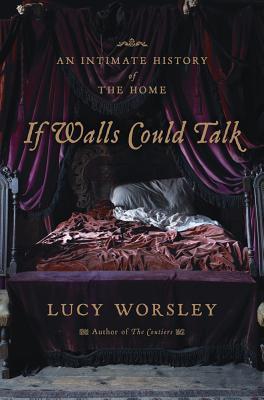

On a Tudor four-poster, the mattress lay upon bed-strings made up of a rope threaded from top to bottom and side to side. This rope inevitably sagged under the sleeper’s weight and required regular tightening up, hence the expression ‘Night, night, sleep tight’.

A feather bed was a prized possession: no wonder, as fifty pounds of feathers had to be saved from the plucking of numerous geese. Sometimes female servants in the kitchen were allowed to keep the feathers of the birds they’d plucked for the table as a kind of dowry, and saved them up for a marital feather bed. Such a bed needs constant punching, turning and shaking to keep it fresh and to disperse the lumps, and a new one was not necessarily more desirable than an old one because of the farmyard scent it would emit.

there was another reason for all the servants: you simply couldn’t get into your clothes without someone else to help. Until buttons were invented in the fourteenth century, you needed an extra pair of hands to fasten up your ‘points’ (the holes through which a string was threaded to attach the sleeves to the body of a gown).

Despite its reputation, the voluminous bloomer was far from risqué, and so was its promoter, Mrs Bloomer herself. A dedicated campaigner for lost causes, married to a Quaker, she was also a stalwart of the Ladies’ Temperance Society. She spoke against drink and in favour of bloomers at rallies all over the US (with limited success).

Towards the end of the Middle Ages, as literacy spread, we come across a novelty: people willingly spending time by themselves. This new trend for solitude, linked to the rise of reading, called for new, small and private rooms.

Until about 1700, most physicians believed that the body was made up of the four ‘humours’, as described by the ancient Roman doctor Claudius Galen, and that illness occurred when one humour grew too powerful and overwhelmed the others. That’s why most medical treatments involved removing liquids of one kind or another from the body.

It would be the factory whistle and the steam train that created the modern toe-tapping attitude to time, in which hours and minutes are carefully demarcated and utilised. Until these developments, events had rarely been timed to the minute. Stagecoaches went when all the passengers were aboard, early-modern workplaces (often in people’s houses) kept quite flexible hours, and meals were served when all the family were present. But the departure of a train or the start of a shift in the mills waited for no man (or woman or child).

The word ‘medieval’ is often – and wrongly – used to mean something primitive, dirty and uncomfortable. This is really unfair to the people of the Middle Ages, where art, beauty, comfort and cleanliness were widely available (at least for those at the top of society). Washing their bodies was an important part of life for prosperous people, and from medieval towns there are numerous records of communal bathing after the Roman model.

The receptacle used for soaking, a big wooden tub, was called the ‘buck’. (Hence the name for the laundry tub’s smaller sibling, the ‘bucket’.)

As the only room in the modern home in which the user can turn a key against his or her family, the bathroom has quite a lot in common with the Stuart closet.

Bazalgette’s work was one of the true marvels of the Victorian age. He would eventually use 318 million bricks to construct over a thousand miles of sewer, and his works to drains, embankments and bridges cost more than twice as much as Brunel’s Great Western Railway. Most remain in use today, underground cathedrals of brick and water.

Below the peers in the Tudor hierarchy (there were only about fifty-five of them in the sixteenth century) came the gentlemen, the citizens, the yeomen and the labourers. William Harrison in 1577 described these four divisions in society, and their respective roles: the labourers and servants, for example, had ‘neither voice nor authority’. Each person knew exactly where they fitted in, and would attempt to decorate their own living rooms appropriately.

The sofa itself was a novel imported Arabian idea. Upon it one could lounge, lean back and spread out one’s skirts, a much more elegant and casual posture than it was possible to adopt in an upright seventeenth-century chair. These sofas were social pieces of furniture, made for two people to sit together. Earlier aristocrats, who sat in stately solitude upon a dais, would not have dreamed of this.

The expression ‘by hook or by crook’ is often said to come from the peasants’ right to enter their landlord’s forest to see what resources they could glean. They were not allowed to cut down trees for firewood; those remained their master’s property. Using either a shepherd’s crook or the billhook of a reaper, though, they might grab dead branches.

Rushlights were the poor person’s light source of choice. They were made by coating rushes in hot fat, building up the layers until the rush itself formed the wick of a rather scrawny candle. These long, gently curving lights could be thrust through and balanced in the holders still found in the walls of ancient houses. To provide twice the light, they could be lit at both bottom and top (‘burning the candle at both ends’). The twenty minutes for which each rushlight burned became a familiar unit of time.

The expression ‘the game’s not worth the candle’ makes it clear that candles were economic units, and to burn a candle gave the sensation of burning money itself.

Westminster Bridge was illuminated by gas as early as 1813, and there would ultimately be more than 60,000 gas street lamps all over London. One thousand six hundred still remain today, in Westminster and around St James’s and Buckingham Palaces. They are maintained by six gas-lamp attendants employed by British Gas, a remnant of the once vast pool of lighters who went round cities at dusk with their long torches.

In Tudor and Stuart times, between a quarter and a half of the entire population were employed in domestic service at some point in their lives, and the bond between master and servant was one of the most important social relationships. Being a servant wasn’t something of which to be ashamed: you gained protection and honour by association with your own particular lord.

In the most significant upheaval in a thousand years of domestic history, by 1951 a mere 1 per cent of households had a full-time residential domestic servant.

In due course, though, industry and retail, with their higher wages and increased social stimulation, became increasingly attractive to the kind of young men or girls who would once have thought to become servants.

there must be some other reason for the inescapable fact that throughout Western society households have been shrinking, not growing, in recent centuries. Households in the West have declined from an average of 5.8 members in 1790 to the current 2.6 in America today.

The doffing of the hat to one’s superior was replaced by a form of greeting which assumed that both parties were equals: England’s new, democratic rulers prided themselves upon refusing to bow, insisting instead upon shaking hands.

silly games like the ‘Laughing Chorus’ described in the Young Ladies’ Treasure Book (1880). To be played ‘round a good fire in the long winter evenings’, ‘the person in the corner by the fire says, “Ha!” and the one next to him repeats, “Ha!” and so on … No one who has not played this game can realise its mirth-provoking capacities.’

The idea that love is the best reason for marriage is quite a modern idea, and one quite specific to the Western world.

‘Trenchers’ were slices of old bread which acted as throwaway plates. They were formed from the burned and blackened bottoms of loaves. The more desirable top crust was eaten at once by the master and guests, hence the enduring term ‘upper crust’ for something posh.

The late seventeenth century saw a burgeoning of feminine roles in the household, as men went out to seek their fortune in the professions instead. The Compleat Servant Maid of 1677 lists ten different jobs for women, from waiting-woman, housekeeper, chambermaid, cook and under-cook to nurserymaid, dairymaid, housemaid, laundress and scullion.

Unpleasant tastes were not remarked upon nearly so often as unpleasant smells or sights, and the word ‘disgust’ (literally ‘unpleasant to the taste’) only entered the English lexicon in the early seventeenth century. ‘Disgust’ is a modern concept: only when food is relatively abundant can people afford to overlook certain forms of nutrition on the grounds of nastiness. In lean, mean times no one found any type of food disgusting.

After the baking of the bread, the oven still contained just enough heat to bake a second round of cakes or biscuits. The very word bis-cuit means ‘second-cooked’.

Tudor people could happily skip breakfast, though, because they didn’t have long to wait until lunch. As soon as enough time had elapsed for the household’s cooks to rise at daybreak, get the fire started and the meat cooked, lunch was ready. The day’s biggest meal was eaten mid- to late morning. The Tudors ate again, more lightly, in the evening.

Another consequence of the Industrial Revolution was the need for workers to eat something substantial first thing. Since Georgian times breakfast for all had been standard, consisting of tea and toast.

The light aristocratic breakfasts of the eighteenth century – tea and toast, coffee and rolls – were replaced by the heavier meals that Victorian gentlemen considered necessary to sustain them during a day at the office (‘a malady of incurable character’ might well result from going to work without the proper fortification).

The separating out of sweet from savoury was an important development of the sixteenth century. One step towards the breakdown of the communal household meal was the new Elizabethan practice of serving the sweets that now followed the main meat course in a different room.

The action of removing the dirty plates from the tables was in French called the desert, the creation of an absence (the same word used for the Sahara). This act of ‘deserting’ the table gave its name to the dessert or sweet course served elsewhere while the entertainers were setting up.

Sugar remained a luxury item into the seventeenth century, when traders’ ships settled down into the ‘triangular’ pattern which sustained both the slave and sugar trades. They took guns from Britain to Africa, captured Africans to work the sugar plantations in the West Indian colonies, and brought back sugar to their starting point of Britain.

Arriving from Mexico, tomatoes, or ‘apples of love’, were grown merely as decorative plants until, in about 1800, people decided to taste them, and concluded that they were delicious.

Until the nineteenth century, dishes tasted only roughly similar each time they were made. About 1800, the modern idea of a standardised recipe appeared. Until then, recipes had been somewhat vague on quantities, length of cooking and temperature.

If a peasant was lucky enough to own a cow, sheep or chicken, he would have valued it far too highly to eat it. Farm animals were for transport, milk, wool or eggs, not food. So the peasant’s meat intake was largely limited to small and nasty creatures: squirrels, wild birds, hedgehogs (‘hogs’ or ‘pigs’ of the hedges).

The concept of the desirability of soft ‘roast’ meat was incredibly powerful, so much so that we still use the word ‘roast’ to describe a joint that’s merely been ‘baked’, in the technical sense, ever since the oven replaced the spit.

76 per cent of the calories in the diet of a medieval peasant would come from bread and pottage.

One thing remained standard throughout the whole history of Britain: people ate lots of grain, whether in the form of pottage, ale or bread.

After industrialisation, threats to health came not from dirty water and inadequately washed raw produce, but from processed, pre-packaged goods containing attractive-looking, quickly absorbed calories which were nevertheless devoid of any lasting nutritional benefit.

A successful ‘place’ mixes up the different groups in society, forcing them to mingle and to look out for each other. In this sense, a great mansion like Hardwick Hall was successful social housing: in it Bess of Hardwick lived within metres of the dozens of people under her care. It was a life of huge inequality, but people were part of a common endeavour. This sounds conservative, but it’s radically so. Today we live lives of vastly varying levels of luxury without really being aware of the alternative experiences of those above and below us in terms of wealth.

We’ve spent too long inside our own snug homes, looking smugly out through the window at the world. There’s a sense in which children are now prisoners of the home, kept indoors by distrustful parents. We don’t know enough about our neighbours,

But change should not be a frightening thing. Throughout all the periods of history, people have thought their own age wildly novel, deeply violent and to be sinking into the utmost depravity; likely, in short, to herald the end of the world. It’s comforting to think that the world has not yet ended, and that the pleasures of home life are perennial: