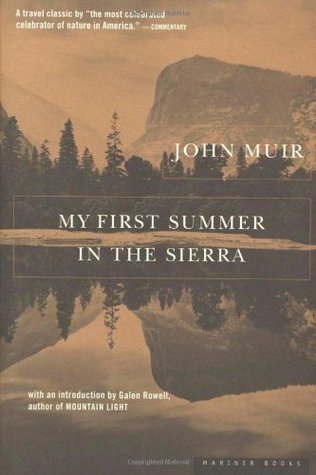

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

In his later life Muir used the power of his fame and the muscle of his prose to help protect wildlands for posterity. He was a prime mover in the creation of the national park that now protects not only the immutable rock features of Yosemite Valley but also the fragile beauty of the high country he so vividly describes in these pages. He also founded the Sierra Club, to which he dedicates this book.

I was a typically smug ten-year-old, and my world view was based on simplistic assumptions. The wild meadows and streams would always be here, along with the peaks and the sky. That the wilderness around me could ever have roads, mines, ski lifts, condos, fast-food stands, or “no trespassing” signs never entered my young mind. It seemed only natural that the words my father read described exactly what was here now and that Muir’s adventures on foot were an anticipation of my own.

And the stars, the everlasting sky lilies, how bright they are now that we have climbed above the lowland dust!

As to tea, there are but two kinds, weak and strong, the stronger the better. The only remark heard is, “That tea’s weak,” otherwise it is good enough and not worth mentioning.

Lying beneath the firs, it is glorious to see them dipping their spires in the starry sky, the sky like one vast lily meadow in bloom! How can I close my eyes on so precious a night?

My first view of the High Sierra, first view looking down into Yosemite, the death song of Yosemite Creek, and its flight over the vast cliff, each one of these is of itself enough for a great life-long landscape fortune—a most memorable day of days—enjoyment enough to kill if that were possible.