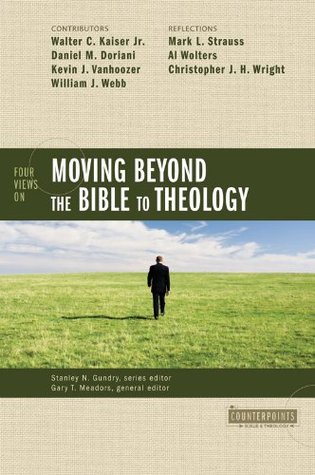

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Zondervan

Started reading

August 21, 2020

We can’t always address contemporary disputes by reciting Scripture, much less the Nicene Creed. Sometimes, to be faithful, we have to be creative. Persons with theodramatic vision will have the mind of Christ, which, as we have seen, is a matter of adopting the same attitude and pattern that characterizes the life of Jesus. When disciples find themselves in strange new territory, they will spontaneously extend the pattern.

Doctrines do not always tell us exactly what to say and do. Their purpose is not merely to give us “answers” but to instill in us habits of seeing, judging, and acting in theodramatically appropriate manners.

Doctrines, by fostering deeper understanding of the drama of redemption, help us to discern what new things we have to say and do in order to be faithful to our canonical script and so move the same action forward in different contexts.

What is authoritative about the Bible, I have suggested, is its theodramatic vision.

Doctrine serves the project of faithful improvisation. Improvising well—knowing how to act both spontaneously and fittingly—requires both training (formation) and discernment (imagination).

The key to good improvisation is knowing how to continue the same action in new situations.

In my view, right understanding involves grasping the relationship between what the Bible says about God and what we know about the contemporary situation, and then acting accordingly (i.e., according to the world implied by the script). As we will see, it is all about fittingness—a concordant relation between diverse parts and a larger whole—both textual/canonical and contextual/situational fittingness. In order to determine what is textually and contextually fitting, the church needs canon sense, catholic sensibility, and a sensitivity to circumstance.

My hope is that minds nurtured on the canon to conform to the mind of Christ will see, judge, and act on the way forward.

to the material point: the church must get on with the principal work of commemorating, celebrating, and continuing the theodrama, performing the world projected by the script in faithful yet creative fashion. When the church demonstrates faith’s understanding, she does what is true, good, and beautiful “in Christ.” Though I have focused on disputed topics here, the real work is to understand the main topic—the gospel—and all that it entails. In sum, our real work as church members is to follow the sacred page where no church has gone before by entering into the theodrama with all our heart,

...more

The drama-of-redemption approach makes room as well for a consideration of what we will term below the world “in front of” the biblical text, and for the way in which the text has been received in the church.

So in moving to theology one needs canon as the magisterial authority and conscience and congregation in ministerial authority. From this footnote we may add "context" to the mix. Context of the text, the original audience and author, and context of the interpreter must be thoughtfully considered in interpretation and direction (application). Vosian biblical theology may assume our contexts today are inconsequential in comparison to the context of those in the New Testament post Pentecost.

The extreme consevative will say contemporary context convolutes the interpretation. The extreme liberal will say context controls interpretation. I think contemporary context must be considered in interpretation/application.

One side assumes their context as normative and overlooks discontinuities while the other dismisses Scripture as the magisterial authority, the norming norm that norms all norms.

The critique of Vos applies to Jim Hamilton too, in my view.

For a critique of the principlizing approach, see David Clark, To Know and love God: Method in Theology (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2003), 91–98. Clark’s main worries are two: that the principles will be seen as better than the Bible, and that the principlizer will fail to recognize his or her own cultural conditionedness.

J. I. Packer agrees: “The basic form of obedient theology is applicatory interpretation” (“In Quest of Canonical Interpretation,” in The use of the bible in Theology: evangelical options, ed. Robert K. Johnston [Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 1997], 44). According to Packer, some truths—mainly about ourselves—we only know and perceive as truth “in the process of actually obeying it”, 54.

For an excellent treatment of how Christian wisdom is connected to virtue and thus to the pedagogy of the Holy Spirit that renews and transforms our minds and hearts, see Daniel J. Treier, virtue and the voice of God: Toward Theology as Wisdom (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2006), esp. 200–202.

The four questions Wright poses are: 1. Who are we? 2. Where are we? 3. What is wrong? 4. What is the solution?

Some authors, of course, are racists, and readers are right to resist them. Yet Christians believe that God is the ultimate author of Scripture and thus are willing to trust the mode-of-life proffered in the text. Thanks to Dan Treier for helping me to clarify this point.

The point stands that an author seeks to direct the readers drama, even if for ill. The author uses the world of the text in his world behind the text to direct his readers into their world in front of the text.

Everyone theologizes and ministers their understanding. This gives me a vision for preaching and writing.

preaching explicitly directs the hearers into their shared world in front of the text