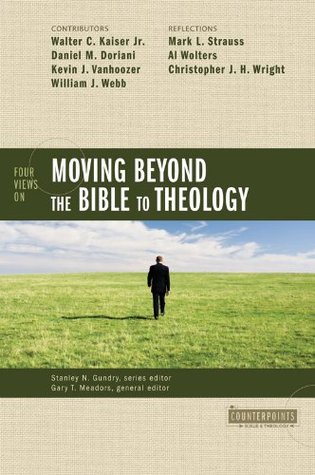

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

The believing community glorifies God by engaging the debate about how the Bible informs contemporary questions it did not always originally envision.

If we claim that exegesis has solved the problem while equally competent scholars disagree about the exegetical products, we have deceived ourselves and perhaps deified our own interpretive judgments.

It is a mistake to assume that disagreement over how the Bible teaches signals a greater or lesser view of the authority of Scripture.

When is a biblical statement normative for all time? We often deal with texts that raise this question with noncritical common sense.

But noncritical common sense can only carry us so far. We need more sophisticated paradigms to determine when the Bible is describing and when it is prescribing and when these two features have been adjusted because we have moved on in time and space. Hopefully, you will walk away from the reading of this volume with a deep realization that “How is the Bible relevant?” is no simple question, but it is one you cannot afford to avoid.

ONE OF THE MOST IMPORTANT INTERPRETIVE TASKS, but the one most laypeople, teachers, and pastors often have had little training in, is the move from determining what a text meant in its original setting and context to applying that text in one’s own day and culture.

In short, the task is not to transform the Bible (i.e., into timeless principles) so that it can enter our world, but to transform ourselves (i.e., our habits of vision) so that we can enter into the world implied by the Bible.

It is not that God couldn’t move (contra Doriani’s incorrect portrayal of a RMH view) the ball all the way downfield and across the goal line of an ultimate ethic. Of course, he could. Rather, he chooses to move the ball incrementally downfield, sometimes twenty, sometimes forty yards at a time.

Human beings are often slow as donkeys and have calcified hearts when it comes to even incremental change for good (Jesus talked about this in his reflection on Scripture).

It was a beautiful day and, as is my custom, I talked to God as I walked. I asked God these sorts of questions: How is it that some Christians, genuine Christ followers, can live out their lives with merely a static understanding of Scripture? How is it that they can think their views strongly uphold biblical authority when in fact (at least from my perspective) they severely diminish it? How is it that they can so vigorously commend the “face value” instructions of the Bible without exploring what an ultimate ethic ought to look like in human relationships? How can they claim that their

...more

It may be that when we no longer know what to do we have begun our real work and that when we no longer know which way to go we have come to our real journey. The mind that is not baffled is not employed. The impeded stream is the one that sings.

The Bible, God’s Word written, is “a lamp to my feet and a light for my path” (Ps. 119:105), but there is some confusion over how to switch it on and some debate over how far ahead it shines.

The challenge of present-day Christian discipleship is to follow the way of Jesus Christ in a very different space and time in which the prevailing ways of life (cultures) bear scant resemblance to the preindustrial, agrarian settings of ancient Israel. John the Baptist had to prepare the way of the Lord (Matt. 3:3); our task is to continue it.

Who is in the best position to lead us to the promised land of right reading, to use the Bible to illumine our pathway through territories known and unknown? Who holds the keys to the kingdom of biblical interpretation? There are many academic pretenders to the theological throne. My own view is that theological interpretation of Scripture—reading the Bible in the church to hear God—is a joint project. We need all the theological disciplines working together in order to think and live biblically. Left to its own devices, each single discipline falls short of cultivating the godly wisdom that

...more

In order to continue biblical Christianity into the contemporary context, it is important to know what kind of road we are traveling. What/who are we trying to follow? To what/whom are we trying to be faithful: a person, a philosophy, a moral code, a tradition, an ancient culture?

What the church seeks to understand is essentially a true story: the history of God’s dealings with his creatures. By story I am thinking not of a particular kind of literary genre so much as a series of events that, when taken together as a unified drama, serve as a lens or interpretative framework through which Christians think, make sense of their experience, and decide what to do and how to do it.

The great merit of a redemptive-historical approach, such as that of Geerhardus Vos, is that it rightly identifies the content of revelation as forming not a dogmatic system but a book of history that unfolds organically.

The Bible, I have claimed, is theodramatic discourse: something someone (prophets and apostles, the Holy Spirit) says about something (the drama of redemption) to someone (the church) at some time (past, present) in some way (a variety of literary forms).

Readers gain understanding when they appropriate—perform!—the worldview proposed by the biblical text by actively following its direction of thought and its design for living. Performative understanding is therefore not a matter of replicating the author’s situation (the world behind the text), or of repeating the author’s words, but of unfolding what the author says (about the theodrama) into one’s own situation (the world in front of the text).

What Christian readers of Scripture are ultimately trying to understand are not principles so much as the divine play described, implied, and projected by the script. Which textual world in particular carries divine authority: the world behind, of, or in front of Scripture?

It is just here that we may begin to appreciate the contribution of Scripture’s diverse literary genres. Though the Bible is always about what is real, it does not always refer to reality in the same way.

In speaking of “performing” the script, then, I have in mind not reproducing the world behind the text or of recreating the scenes depicted in the text but rather of living in a way that conforms to the world as it is being transformed “in Christ.”

It should now be clear that “performing the script” is in fact shorthand for living in the world implied by the script. Note that “living the Bible” is not quite the same thing as “applying the Bible.” How can we “apply” the story of Paul and Silas in prison (Acts 16:16–34) today? It’s straightforward—if one is ever in first-century Philippi in prison for exorcising the demon of a slave girl and there was an earthquake during your midnight hymn-sing!

A canonical performance, however, is neither strict replication of a prior blueprint nor application of a principle. It is rather a lived demonstration of theodramatic understanding. The story in Acts 16 shows us the kind of world we live in and the kind of thing God does in the world and the kind of people we are to be in response. To read this passage wisely is not to apply but to appropriate its message and hence “of being transformed by watching/hearing it properly, as a word about who this God is that we are trying to know and love.”

Moving “beyond” the sacred page involves more than applying it; it involves renewing and transforming people’s habits of seeing, thinking, and acting. Scripture is not merely a vehicle for conveying information. It is rather a medium of divine communicative action whose purpose is not only to inform but to transform: to nurture right vision, right attitudes, right actions.

Disciples must practice the three Ds: they must discern, deliberate on, and do what citizens of the kingdom of God would do in this or that situation.

Improvising well—knowing how to act both spontaneously and fittingly—requires both training (formation) and discernment (imagination). It is not a matter of being clever and original but of learning “to act from habit in ways appropriate to the circumstance.”

In order to determine what is textually and contextually fitting, the church needs canon sense, catholic sensibility, and a sensitivity to circumstance.

Christians perform the kingdom of God by continuing Christ’s way, staging scenes of love and justice, holy living and forgiving, wherever two or three are gathered in his name. The church makes known the theodrama—the good news of God doing—by staging what for lack of a better term we could call world-for-world translations of the Bible, unfolding the world implied by the canonical text in terms of its own contemporary context.

There is no slide-rule or computer program for good translation, nor is good judgment arrived at by mere calculation. No procedure or method can guarantee the right result, for the simple reason that good judgment is a capacity that involves the heart and will as well as the intellect.

Those who cannot see their own cultural conditioning are doomed to repeat it.

As Andrew Walls has observed, the wonderful thing about translating the gospel into other languages and cultures is that these translations lead to an enlarged understanding of the gospel itself.

To live biblically is not to re-create the past but to resonate in the present. The church “resounds” to God’s glory not by replicating the self-same sound again but by filling space and time with booming, echoing sympathetic vibrations—sound and shock waves from the big bang of resurrection. Subsequent church performances resonate with the script when they “ring true”—to use the motto of my Cambridge college—even at a distance.

God is the creator of everything that is, so that everything that has being—everything that is—also has a measure of his truth, goodness, and beauty.

Fittingness is ultimately a matter of “rightly ordered love,” of love that has been trained to know truth, do good, and sense beauty.

disciples must not only admire but appropriate the truth, goodness, and beauty of Jesus Christ for themselves.

I encourage Christians to embrace the redemptive spirit of the text, which at times will mean that we must move beyond the concrete specificity of the Bible. Or, we must move beyond the time-restricted elements of the Bible. Or, we must be willing to venture beyond simply an isolated or static understanding of the Bible.1 Or, we must progress beyond the frozen-in-time aspects of the ethical portrait found within the Bible.

In broad terms Christians often tend toward one of two ways of approaching the Bible: (1) with a redemptive-movement (RM) or redemptive-spirit appropriation of Scripture, which encourages movement beyond the original application of the text in the ancient world, or (2) with a more static or stationary appropriation of Scripture that locks itself into the concrete specificity of, or as close as possible to, exactly what is found on the page.

movement meaning, captured from reading a text in (1) its ancient historical and social context and (2) its canonical context, which yields a sense of the underlying spirit of the biblical text.

if we are going to read the biblical text with all of its intended meaning and not lose important components of that meaning, then we must read the text within the ancient-world context and its canonical context.

Moving large, complex, and embedded social structures along an ethical continuum is by no means a simple matter. Incremental movement within Scripture reveals a God who is willing to live with the tension between an absolute ethic in theory and the reality of guiding real people in practice toward such a goal.

For simply to read the text and do what it says on the page often misreads and misapplies the text. Such static methods produce museum-piece approaches to Christian ethics and an impoverished way of applying the Bible.

Christians must journey far beyond any surface-level appropriation of Scripture to an application of the text that listens intently to its movement meaning as heard within its historical and canonical contexts.

Our task as Christians is not to stay with a static understanding of Scripture but to champion its redemptive spirit in new and fresh ways that logically and theologically extend its movement meaning into today’s context.

the most painful wounds are those inflicted by friendly fire.

Two questions are foundational for any hermeneutical discussion of this kind. The first is: What is the Bible? And the second: How does God communicate to us through it?

As divine-human communication, the Bible is both historically positioned and culturally conditioned. The former means that every part (whether narrative, psalm, letter, law, proverb, etc.) was written by historical persons at particular places and times to meet certain needs and concerns of that time.

The Bible is not made up primarily of abstract or propositional statements of truth, but of historically situated “speech acts” or “utterances”—communicative acts from one person to another person or community.

How do we go “beyond the Bible” in this model? Like travelers crossing from rural farmland to an urban metropolis, we in the modern world encounter new opportunities, challenges, and threats. We face these by learning the ways of God in the past and by experiencing his guidance in the present.

It should be noted that the goal is not, strictly speaking, to identify which commands in the Bible are cultural and which are supracultural. All commands in the Bible are cultural in that they are given within the context of human culture. Nor are we distinguishing between commands intended for an original audience (say, Timothy, or the churches in Asia Minor) and those intended for all believers. Virtually all commands in Scripture were intended for a specific audience, whether a nation (Israel), a particular church or churches, or an individual. What we are seeking is the divine ethic

...more