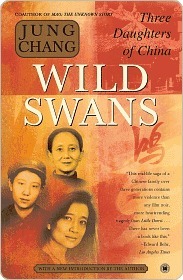

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Following the custom, my great-grandfather was married young, at fourteen, to a woman six years his senior. It was considered one of the duties of a wife to help bring up her husband.

But her greatest assets were her bound feet, called in Chinese ‘three-inch golden lilies’ (san-tsun-gin-lian). This meant she walked ‘like a tender young willow shoot in a spring breeze’, as Chinese connoisseurs of women traditionally put it. The sight of a woman teetering on bound feet was supposed to have an erotic effect on men, partly because her vulnerability induced a feeling of protectiveness in the onlooker.

In fact, a good woman was not supposed to have a point of view at all, and if she did, she certainly should not be so brazen as to talk about it. He would quote the Chinese saying, ‘If you are married to a chicken, obey the chicken; if you are married to a dog, obey the dog.’

When he asked my grandmother if she would mind being poor, she said she would be happy just to have her daughter and himself: ‘If you have love, even plain cold water is sweet.’

She was a pious Buddhist and every day in her prayers asked Buddha not to reincarnate her as a woman. ‘Let me become a cat or a dog, but not a woman,’ was her constant murmur

The need to obtain authorization for an unspecified ‘anything’ was to become a fundamental element in Chinese Communist rule. It also meant that people learned not to take any action on their own initiative.

This was a traditional Chinese dream, which has entered the language as yi-jin-huan-xiang, ‘returning home robed in embroidered silk’.

After the Communists took power this type of unspoken stigma was attached to any part of the revolution which Mao had not directly controlled, including the underground, which included many of the bravest, most dedicated—and best educated—Communists.

A popular saying summed up the atmosphere: ‘After the Three Antis no one wants to be in charge of money; after the Anti-Rightist Campaign no one opens their mouth.’

‘Capable women can make a meal without food’, a reversal of a pragmatic ancient Chinese saying, ‘No matter how capable, a woman cannot make a meal without food.

whole nation slid into doublespeak. Words became divorced from reality, responsibility, and people’s real thoughts. Lies were told with ease because words had lost their meanings—and had ceased to be taken seriously by others.

Another means of regimentation, setting up canteens in the communes, was an obsession with Mao at the time. In his airy way, he defined communism as ‘public canteens with free meals’. The fact that the canteens themselves did not produce food did not concern him. In 1958 the regime effectively banned eating at home. Every peasant had to eat in the commune canteen.

Chinese always yearned for—so much that they said ‘It’s better to be a dog in peacetime than a human being in war.’

Like many Chinese, I was incapable of rational thinking in those days. We were so cowed and contorted by fear and indoctrination that to deviate from the path laid down by Mao would have been inconceivable.

Besides, we had been overwhelmed by deceptive rhetoric, disinformation, and hypocrisy, which made it virtually impossible to see through the situation and to form an intelligent judgment.

‘Where there is a will to condemn, there is evidence,’ as the Chinese saying has it.

In January 1969, every middle school in Chengdu was sent to a rural area somewhere in Sichuan. We were to live in villages among the peasants and be ‘reeducated’ by them. What exactly they were supposed to educate us in was not made specific, but Mao always maintained that people with some education were inferior to illiterate peasants, and needed to reform to be more like them. One of his sayings was: ‘Peasants have dirty hands and cowshit-sodden feet, but they are much cleaner than intellectuals.’

The daughter of an ambitious small-town policeman, concubine to a warlord, stepmother to an extended but divided family, and mother and mother-in-law to two Communist officials—in all these circumstances she had little happiness.

Sometimes, in an ironic mood, I would contemplate whether our new leaders—Chairman Mao was still beyond questioning—would want me as their personal doctor, barefoot or not. But then, I told myself, of course not: barefoot doctors were supposed to ‘serve the people, not the officials’ in the first place.

Saving precious food for others has always been a major way of expressing love and concern in China.

It was only in persecuting people and in destruction that Mme Mao and the other luminaries of the Cultural Revolution had a chance to ‘shine’. In construction they had no place.

Under Mao, as in the days of the Middle Kingdom, the Chinese placed great importance on holding themselves with ‘dignity’ in front of foreigners, by which was meant appearing aloof, or inscrutable. A common form this took was to show no interest in the outside world, and many of my fellow students never asked any questions.

But Mao’s theory might just be the extension of his personality. He was, it seemed to me, really a restless fight promoter by nature, and good at it. He understood ugly human instincts such as envy and resentment, and knew how to mobilize them for his ends. He ruled by getting people to hate each other. In doing so, he got ordinary Chinese to carry out many of the tasks undertaken in other dictatorships by professional elites. Mao had managed to turn the people into the ultimate weapon of dictatorship.

The other hallmark of Maoism, it seemed to me, was the reign of ignorance. Because of his calculation that the cultured class were an easy target for a population that was largely illiterate, because of his own deep resentment of formal education and the educated, because of his megalomania, which led to his scorn for the great figures of Chinese culture, and because of his contempt for the areas of Chinese civilization that he did not understand, such as architecture, art, and music, Mao destroyed much of the country’s cultural heritage. He left behind not only a brutalized nation, but also

...more

They had had only Mao. The Gang of Four had held power only because it was really a Gang of Five.

We in China had been trained not to draw conclusions from facts, but to start with Marxist theories, or Mao thoughts, or the Party line, and to deny, even condemn, the facts that did not suit them.