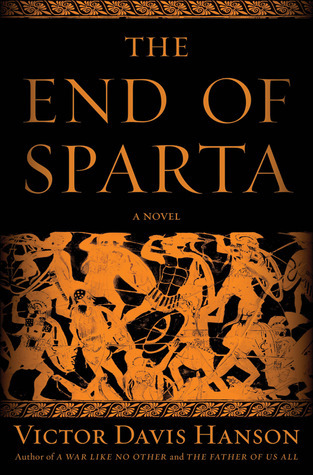

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Whatever he believed in, he had believed in for a long time—and had fought for it, too. The nondescript, the poor and needy looking, these are far more dangerous revolutionaries than those with gold clasps and purple cloaks.

Birth and money, and his white teeth and black beard, gave him a certain arrogance that comes when a man feels bigger and stronger and richer than those around him.

How strange, Mêlon went on to lecture his Chiôn, that the odious among us can teach us the most—if we only can endure their cuts and jibes and then learn from their very mouths how not to view the world about us, and yet how with just a slight shove we might become as they are.

She gives me a chance to hear my dark thoughts spoken, hear it all said by another, not me. Then I redeem myself by sneering at it, and claim the high ground from it, when she turns everything so foul and has no shame to voice the evil in us that we too feel.”

A farm is the stored work of a man’s life.

Without young men who know it not, there could be no war brought to the land of others. So war is a sort of madness. It requires young men in their pride and recklessness who have no wisdom about how thin the threads of all of us hang—and so are willing to confront evil.

Is not ‘right’ anyway a relative thing, and always dressed up as the ‘good’ by the man with the heaviest fist?

Old Herodotus had it right: It is easier to get thousands of hotheads in a democracy to muster than to win over a few stern-faced oligarchs.

So scribble down your thoughts. He who doesn’t write, dies.

Why were men poor? Because of accident or hurt, or was it rather due to their sloth—poor because they were no good by nature inside? Or drank the unmixed wine? Or stole, and killed and maimed when they should have been pruning the high olive trees?

So what does it matter that some good men are slaves, some free men are bad? That men who were by nature equal, yet were slave and master, spoke nothing to him more than the clever fox who was eaten by the savage wolf, or the cowardly knight who rode atop the brave horse. “Nature’s unfair way is sometimes nature’s way.”

Yet I remind you only that freedom won after these hundreds of years can just as easily be lost again in one—should the nerve of your newfound democracy fail and you let your shields slack to your knees. It is the nature of all men in peace to become soft and scoff at the prior hard work of their fathers who gave them such bounty. Beware the real enemy is the smoother second thought that always mocks the rougher first.

“You have it wrong, all of you. God has made every man a slave. Only a man, if he’s worth anything, makes himself free.”

Worse men worry whether the Gorgones of the world are given a good burial, the better only that they are dead. Terrible souls fret that Gorgos might have been a bit good, better ones know that it mattered little since he was mostly bad.

For I too was freed from a different sort of slavery, one worse in some ways: a slavery of the mind—and of the soul that once believed in nothing other than itself. Nothing is worse than the cynic who is disappointed by the world about him for not appreciating in his own genius, for being less than perfect.

So it is with all wars, that both supporters and critics weave and warp until the final story is known—and alike then go back with their plumb strings to line up their past principles with the final verdict of the last battlefield.