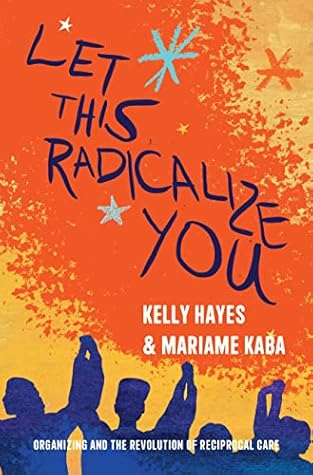

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Kelly Hayes

Read between

May 11 - May 16, 2025

As Angela Davis says, “radical” means “‘grasping things at the root,’”

“We are in a space without a map. With the likelihood of economic collapse and climate catastrophe looming, it feels like we are on shifting ground, where old habits and old scenarios no longer apply.”

To understand the past, we must investigate the stories we were not told, because those stories were withheld for a reason.

We must search out all the pieces we weren’t meant to find, the things that disrupt the narratives we’ve been given.

While others were going door to door in Harlem to talk with community members about affordable housing, the butterflies were lamenting the fact that “the people” were not being sufficiently engaged in “our” struggles. None of them ever went door to door.

“What have you built?” he asked. I must have looked perplexed. So he asked me again, “What have you built?”

It turned out that I hadn’t “built” anything. He was asking me, Who are the people to whom you’re accountable? When had I been brave enough to actualize and execute the ideas and theories that I was always so quick to offer to others? What was I actually doing?

no never meant no for Black and brown women (and some poor white women). This idea has carried over, I think, to the concept of “self-defense” as applied to Black and brown women. If Black women’s bodies can always be violated and if Black women are easily killable, then the notion of self-defense can never apply.

Activism encompasses all the ways we show up for justice. It can take a multitude of shapes, depending on a person’s skills, interests, and capacity. An activist might conduct research, canvass, fundraise, or attend marches or meetings regularly, or they may simply practice a skill in their own home, such as art making, in the service of a cause or campaign they support. Activism can be done on our own, in which case we are accountable to ourselves. Activists are essential, whether or not they are also organizers.

Organizing, on the other hand, is a more specific set of practices. It is a craft that requires us to cultivate a variety of skills, such as intentional relationship building and power analysis.

“There are people who are in motion, who may be the people who go to demonstrations, who go to rallies, who go to vigils or advocate or write or express their solidarity with a movement in various kinds of ways, but they’re not necessarily the people who are, in a strategic methodical way, trying...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Those protest attendees are activists, while the movement builders are organizers. “I think of organizers,” Ransby told us, “as people who really are trying to move other people, [and] create collective movement in a very conscious, delibera...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

No matter how we choose to take action, we are usually working toward a future that we will be unlikely to see.

organizers often raise the alarm about present or future catastrophes. Our work is usually informed by a daunting awareness of the crises we face.

it’s easy to assume that if others knew how bad things were, they, too, would want to take action. This assumption can sometimes lead activists to become walking, talking encyclopedias of doom.

In 2018, Chris Hayes, host of MSNBC’s All In with Chris, tweeted, “Every single time we’ve covered [climate change] it’s been a palpable ratings killer.”

fear alone doesn’t usually hold people’s attention, let alone inspire them to action.

The kind of engagement Gilmore describes is key to creating a sustainable flow of communication, education, and potential inspiration. Everything is a story, and people need to understand themselves as having a meaningful role within the story you,

If their role in your story feels like “doom appreciator,” most people will recoil, retreat to their own smaller story, and keep the focus there.

Some people react to a public health crisis with what scientists call “monitoring” behavior. To cope with uncertainty, monitors seek all available information, such as reading as many news updates as possible or checking for new information on government websites.

what’s known as “blunting” behavior, which involves “the distraction from, and minimizing of threatening information.”

“unrealistic optimism bias,” characterized by the belief that they are more likely than others to evade harm and experience positive outcomes.

monitors are responsive to emotional appeals as well as detailed information about risk factors and harm reduction strategies, whereas blunters are likely to avoid such messaging; for them,...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

the matter would come down to persistent, patient, and curious conversations and story sharing.

defines mutual aid as “when people get together to meet each other’s basic survival needs with a shared understanding that the systems we live under are not going to meet our needs and we can do it together RIGHT NOW!”

points to climate activism as an area that overwhelmingly relies upon fear-based communication, and she gestures toward a different path. “We do need to tell stories that evoke emotion,” she says, “and fear is an emotion, but it is not the only emotion available to us. There are many other emotions we can tap into.”

“We can use admiration,” says McDavis-Conway, “like admiration for Indigenous activists who are fighting pipelines. We can tap into nostalgia for coastal cultures. They’re impacted by rising sea levels. We can tap into love and sadness and excitement, outrage, even disgust.”

We must also continue to create our own works of visual art, fiction, and poetry that drive people to envision cooperation and mutual aid as our primary responses to crisis.

In order to overcome these impediments, organizers must work to construct anchors that can provide a coherent understanding of the world in catastrophic times and help people maintain their values and commitments. If we do not take the work of anchoring seriously, we may find that our ships scatter or even sink with every strong gust of wind.

Anchors can take numerous shapes: a story, a community space, a sense of fellowship, a memorial—anything that helps ground people in a shared sense of history, compassion, and purpose.

People come into movement spaces for a variety of reasons, but one that we rarely name or recognize is that we have a basic human desire to belong, and our competitive, commercial, individualistic society does not foster belonging.

“We have to intentionally build a culture of belonging that embraces the time and space for healing work as part of that culture.”

Frameworks that treat activists as mere unpaid labor, or as bodies to arrange for photo ops, without cultivating hope, purpose, or belonging for those individuals—or granting them any power in the entity they work within—can lead to frustration and burnout and cause many people to drop out of movements.

Radha Agarwal writes that belonging is “a feeling of deep relatedness and acceptance; a feeling of ‘I would rather be here than anywhere else.’”

“belonging is the opposite of loneliness. It’s a feeling of home, of ‘I can exhale here and be fully myself with no judgment or insecurity.’

Belonging is about shared values and responsibility, and the desire to participate in making your community better. It’s about taking pride, showing up, and offering your unique gif...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

in prison functioned in opposition to abandonment and that imprisoned people often defy the system by “refusing to abandon each other.”

it revolves around a key principle: “If you show up for people, they show up for you.” She engages with people accordingly, whether she is interacting with neighbors in her apartment building or working with organizations.

In practice, showing up for people can look like bringing someone food when they are ill, cop-watching (observing and documenting police activity in order to discourage or bear witness to police violence) if a neighbor has to deal with police, listening and extending comfort to someone experiencing an emotional crisis, or offering to lighten someone’s load if they are overworked.

As fires rage and sea levels rise in the coming years, we will be called upon to rescue one another again and again. That impulse—to find our boats after a storm and to pull each other from the water on unauthorized, community-led rescue missions—will be key to surviving these times and to the creation of a new future.

emphasizes the need to build community, rather than brave violent onslaughts alone or in small groups.

Like an electrical current that reactivates a stopped heart, crisis can create a social defibrillation that re-enlivens our connectedness to other human beings and allows our compassion, imaginations, and political will to flow more freely.

many people coping with the grief, uncertainty, and isolation of the pandemic longed to connect through acts of aid and care, and they did.

One popular method of organization that people engaging in mutual aid practiced during the pandemic was the formation of mutual aid “pods.” Pods are a model for community care and collaboration developed by disability activist Mia Mingus in which small, autonomous groups of people practice various forms of mutual aid and collaborative support. Mutual

the supposed light at the end of the tunnel is a “return to normalcy” concocted by a government eager to restore the status quo that delivered us to this moment.

There is also little focus on commemoration or memorialization, because the primary objective of the powerful is the restoration of economic stability, which means we should be shopping, dining out, and investing, rather than mourning and contemplating how we can prevent a tragedy of this scale from ever happening again.

The bonded energy of protesters in the streets can help sustain the momentum of a protest, but it does not, in and of itself, create a sustained capacity for organized political action.

important to remember that social media platforms are corporate products governed by algorithms and human beings who have repeatedly stifled leftist voices, obscured state violence, and facilitated right-wing radicalization.

We also have to prepare for the eventualities of becoming a threat to the status quo. The more successfully our work challenges the status quo, the more likely social media platforms and other digital services are to blacklist us or otherwise impede our efforts.

If you are a young person, you will surely see evolutions in technology that will both aid and impede your work in the coming decades.