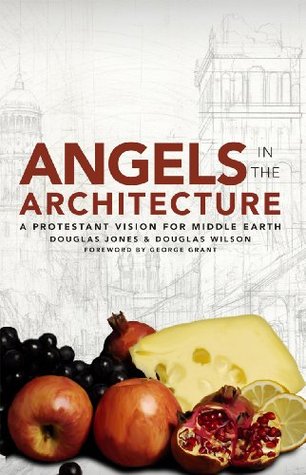

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

December 17 - December 23, 2023

The medieval period is the closest thing we have to a maturing Christian culture. It was a culture unashamed of Christ and one sharply at odds with the values of modernity. Where else can Christians look for a vision of normal life, of Christianity enfleshed? Do we look to the 1950's? Life on the American prairie? To Jefferson's reign? Modernism had already gutted Christian culture long before any of these.

When the prophets and apostles turn to describe this holiness, it is remarkable that they do not use phrases like the "kindness of holiness," or the "goodness of holiness." When called upon to speak concerning what holiness is like, they overwhelmingly speak of the beauty of holiness.

When we sing "Immortal, invisible, God only wise," only a fool would think to set the hymnal aside after the first verse because he has exhausted the subject.

In His grace and mercy, He does not require us to speak of Him exhaustively. A good place to learn this lesson is from the poets. When using poetry we are most clear on the point. God's providences are traced upon our dial by the Sun of love. We take the royal diadem to crown Him Lord of all. Our God is a fortress, a bulwark never-failing.

The exuberance characteristic of the early Protestants

wasn't the thin fanaticism of a Finney revival, but the life-changing shock of unexpected liberation, the joy of justification in Christ.

When the child comes, God insists he be named Isaac, which means he laughs (Gen. 17:19). The child of promise is a promise of laughter.

In this futile world, in this world where vanity reigns, we can know that the grace of God has burst through to us by one indication only: "Go thy way, eat thy bread with joy, and drink thy wine with a merry heart; for God now accepteth thy works" (Ecc. 9:7).

A creedal church is one in which the words I believe in God the Father Almighty provoke tears of gladness in strong men.

By contrast, poetic knowledge, which is essential to

a recovery of the medieval mind, values precision through imprecision, extensive sic et non qualification, authoritative concrete images, and oblique correlations of wisdom to the creation. And this because we can never know if we have handled a poem as well as a multiplication table, which brings us to consider the characteristics of what may be called the poetic mind.

The modernist historian wants to count and quantify everything and does not believe he may name until he has discovered the real name "inside" the subject he studies. But a poet can read through an account of the battle of First Manassas, and say that Stonewall Jackson was the epitome of Southern manhood. And he was.

My girlfriend is quite pretty is a straightforward statement, simple to understand, and yet it tells us far less than My love is like a red, red rose. Or, to take another example, God is immutable is entirely accurate and precise, and yet it tells us less than the statement God is like a mountain, never changing. The second statement is less precise in terms of scientific theology, but at the same time it accurately conveys much more of the truth-to the one who understands poetry.

When the Confederate States of America surrendered at Appomatox, the last nation of the older order fell. So, because historians like to have set dates on which to hang their hats, we may say the first Christendom died there, in 186 5. The American South was the last nation of the first Christendom.