More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

I was running the risk of becoming trapped in my own fantasies.

Why does what was beautiful suddenly shatter in hindsight because it concealed dark truths? Why does the memory of years of happy marriage turn to gall when our partner is revealed to have had a lover all those years? Because such a situation makes it impossible to be happy? But we were happy!

Yeah... we often consider an experience as unpleasant because it didn't end happily and ignore all the happiness and fulfilment we had.

When I see a woman of thirty-six today, I find her young. But when I see a boy of fifteen, I see a child. I am amazed at how much confidence Hanna gave me. My success at school got my teachers’ attention and assured me of their respect. The girls I met noticed and liked it that I wasn’t afraid of them. I felt at ease in my own body.

My understanding: He benefited from the relationship even tho it ended painfully and he was ashamed of it.

There was a long stretch when I did not dare ask myself whether I would rather be at the swimming pool or with Hanna. But on my birthday in July, there was a party for me at the pool, and it was hard to tear myself away from it when they didn’t want me to go, and then an exhausted Hanna received me in a bad mood.

THEN I BEGAN TO BETRAY HER. Not that I gave away any secrets or exposed Hanna. I didn’t reveal anything that I should have kept to myself. I kept something to myself that I should have revealed. I didn’t acknowledge her. I know that disavowal is an unusual form of betrayal. From the outside it is impossible to tell if you are disowning someone or simply exercising discretion, being considerate, avoiding embarrassments and sources of irritation. But you, who are doing the disowning, you know what you’re doing. And disavowal pulls the underpinnings away from a relationship just as surely as

...more

It was just as evident that conviction of this or that camp guard or enforcer was only the prelude. The generation that had been served by the guards and enforcers, or had done nothing to stop them, or had not banished them from its midst as it could have done after 1945, was in the dock, and we explored it, subjected it to trial by daylight, and condemned it to shame.

I am sure that to the extent that we asked and to the extent that they answered us, they had very different stories to tell.

My father did not want to talk about himself, but I knew that he had lost his job as a university lecturer in philosophy for scheduling a lecture on Spinoza, and had got himself and us through the war as an editor for a house that published hiking maps and books. How did I decide that he too was under sentence of shame? But I did. We all condemned our parents to shame, even if the only charge we could bring was that after 1945 they had tolerated the perpetrators in their midst.

We should not believe we can comprehend the incomprehensible, we may not compare the incomparable, we may not inquire because to inquire is to make the horrors an object of discussion, even if the horrors themselves are not questioned, instead of accepting them as something in the face of which we can only fall silent in revulsion, shame, and guilt. Should we only fall silent in revulsion, shame, and guilt? To what purpose? It was not that I had lost my eagerness to explore and cast light on things which had filled the seminar, once the trial got under way. But that some few would be convicted

...more

‘Did you not know that you were sending the prisoners to their death?’ ‘Yes, but the new ones came, and the old ones had to make room for the new ones.’ ‘So because you wanted to make room, you said you and you and you have to be sent back to be killed?’ Hanna didn’t understand what the presiding judge was getting at. ‘I… I mean … so what would you have done?’ Hanna meant it as a serious question. She did not know what she should or could have done differently, and therefore wanted to hear from the judge, who seemed to know everything, what he would have done.

‘So should I have … should I have not … should I not have signed up at Siemens?’ It was not a question directed at the judge. She was talking out loud to herself, hesitantly, because she had not yet asked herself that question and did not know whether it was the right one, or what the answer was.

That was also why she had refused the promotion at Siemens and become a camp guard. That was why she had admitted to writing the report in order to escape a confrontation with a handwriting expert.

My father was undemonstrative, and could neither share his feelings with his children nor deal with the feelings we had for him. For a long time I believed there must be a wealth of undiscovered treasure behind that uncommunicative manner, but later I wondered if there was anything behind it at all. Perhaps he had been full of emotions as a boy and a young man, and by giving them no outlet had allowed them over the years to wither and die.

‘No, your problem has no appealing solution. Of course one must act if the situation as you describe it is one of accrued or inherited responsibility. If one knows what is good for another person who in turn is blind to it, then one must try to open his eyes. One has to leave him the last word, but one must talk to him — to him and not to someone else behind his back.’

couldn’t stand it. I jumped up and went over to the next table. ‘Stop it!’ I was shaking with outrage. At that moment, the man half hobbled, half hopped over and began fumbling with his leg; suddenly he was holding the wooden leg in both hands. He brought it crashing down onto the table so that the glasses and ashtrays danced, and fell into an empty chair, laughing a squeaky, toothless laugh as the others laughed in a beery rumble along with him. ‘Stop it!’ they laughed, pointing at me. ‘Stop it!’

I believed that there was progress in the history of law, a development towards greater beauty and truth, rationality and humanity, despite terrible setbacks and retreats.

I thought that if the right time gets missed, if one has refused or been refused something for too long, it’s too late, even if it is finally tackled with energy and received with joy. Or is there no such thing as ‘too late’? Is there only ‘late’, and is ‘late’ always better than ‘never’? I don’t know.

I didn’t want to visit her. I had the feeling she could only be what she was to me at an actual distance. I was afraid that the small, light, safe world of notes and cassettes was too artificial and too vulnerable to withstand actual closeness.

Instead of accepting this, I kept searching, harassed, obsessed, anxious, as though reality itself could fail along with my concept of it, and I was ready to twist or exaggerate or play down my own findings.

I saw her on the bench, her eyes fixed on me, saw her at the swimming pool, her face turned to me, and again had the feeling that I had betrayed her and owed her something. And again I rebelled against this feeling; I accused her, and found it both shabby and too easy, the way she had wriggled out of her guilt. Allowing no one but the dead to demand an accounting, reducing guilt and atonement to insomnia and bad feelings — where did that leave the living? But what I meant was not the living, it was me. Did I not have my own accounting to demand of her? What about me?

She seemed insignificant until she began to speak, with force and warmth and a severe gaze and energetic use of both hands and arms.

As I looked and looked, the living face became visible in the dead, the young in the old. This is what must happen to old married couples, I thought: the young man is preserved in the old one for her, the beauty and grace of the young woman stay fresh in the old one for him. Why had I not seen this reflection a week ago?

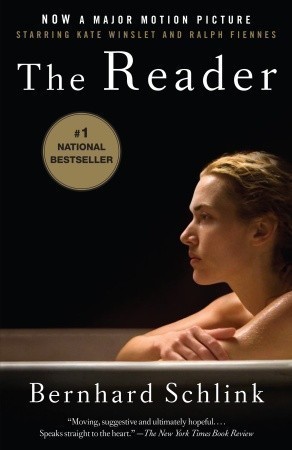

Set in post-war Germany, The Reader begins as an erotic love story but later becomes a philosophical enquiry into the effects of the Holocaust on a generation whose parents are perceived as at best complicit, at worst perpetrators. Central to the novel is the question: what is to be done with the knowledge and the guilt of the Holocaust?