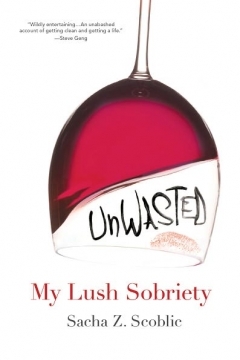

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

December 19 - December 20, 2021

“No thanks, I don’t drink,” I said apologetically, certain I had just irrevocably denounced the possibility of a good time that night, rebuffed her sweet attempt at inclusion, and declared myself a Mormon all in one fell swoop.

Nothing scared me more than going to bed sober, alone with my head.

What I had yet to learn was how little people cared about whether I drank or not—and how little I needed to concern myself with what people did think.

parties without drinking were really just a lot of people standing in the same room,

There’s no time to make lunch ahead of time, no time to eat right, to walk the dog, to get to the gym, to have energy, to appear happy, to make an appearance. But all of these people want something from me, and it just got to be too much.

suddenly you realize that everything is a bar now: the coffee bar, the frozen-yogurt bar, the chocolate bar, the pizza bar—and there is nowhere left to run except straight to the dive liquor store that sells the hard stuff with no bullshit on the side,

the cocktail hours that precede an event such as, say, a wedding can end up feeling like some yawning expanse, a meaningless pocket of time designed to crush your spirit early so that the rest of the evening—with its mass-produced chicken entrées and droning emcee—will seem tolerable.

Cocktail parties are kind of like being trapped on a lifeboat on the ocean, surrounded by water with nary a drop to drink.

It is important, whether at a happy hour or at a party, to have a solid exit strategy ahead of time.

Unfortunately, leaving is generally a multistage process that can take a good half an hour—if you’re lucky.

Kirstin knew herself, and her confidence was intoxicating. Were we each to get a bad haircut, Kirstin would immediately reproach the hairdresser, demand a fix, leave looking fantastic, and only pay half; I would say my haircut was fine, overtip, go home, try to fix it myself, and then wear a hat for the next month.

Already living life underwater, I grabbed at other people’s legs as they swam by and tried to pull them down with me.

I have regretted the many relationships I lost to my staggering inability to return phone calls or letters, rued the carelessness with which I treated friendships, and have been crushed by the guilt and embarrassment of feeling it is too late to try now.

making friends without booze was clumsy and sometimes embarrassing.

Why did I always feel entitled to fill the void with something that was bad for me?

the void inside me must be filled with something that makes me feel awful about myself.

my challenge is either to fill the void with something that does not invite misery or else to make peace with the void.

no one got that I needed more and more and more and more. I had more of a thirst than most people. I was just special that way.

that was the biggest lie I told—and I told it to myself. I didn’t need more of anything; I just wanted more.

Nothing quite helps me achieve serenity more than the knowledge that I have done nothing wrong that day, that I have lied to no one, that I have nothing to feel guilt or panic over.

When you finally realize how much you have, it’s pretty hard to feel entitled to more.

people of faith live longer than those without it, meditation reduces disease indicators and stress, and patients who pray recover faster than those who don’t. Perhaps the energy of the universe, the tide along which we all roll, is worth at least thinking over. Perhaps prayer, meditation, chanting, and ritual are all just ways of honing the ham radios of our minds and tuning in.

Here’s the thing about people: They don’t do what you want when you want them to. Even when you really, really want them to.

I saw one coworker throw back whiskey with relish, and I felt as though I might as well be seeing him shoot up heroin, slice off a finger with a butter knife, and jerk off onto the dining room table.

It is no wonder James Frey felt he had to lie and embellish in A Million Little Pieces; everybody these days seems to think you aren’t yet a real addict until you’ve shot a man for crack, drank until your eyes bled, and swaddled yourself in tattoos. But there’s no competition to see who is more or less of an addict; because in a very fundamental way, we are all the same. My disease is the same as every addict’s, even the shotgun-toting, eye-bleeding, tattooed crackhead alcoholic. I just stopped sooner. Hopefully, I will never find out how much farther down the rabbit hole I might have gone.

I realized that I hadn’t known everything, that the “possible” consisted of more than what I had experienced or conceived in my own head.