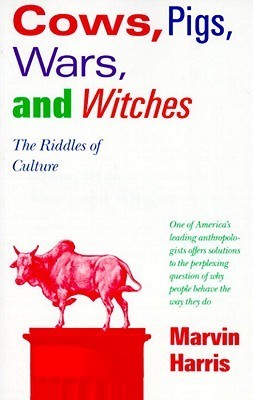

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

December 27, 2019 - January 2, 2020

Ditto for why the Hindus refrain from eating beef, or the Jews and Moslems abhor pork, or why some people believe in messiahs while others believe in witches. The long-term practical effect of this suggestion has been to discourage the search for other kinds of explanations. For one thing is clear: If you don’t believe that a puzzle has an answer, you’ll never find it.

Over the years I have discovered that lifestyles which others claimed were totally inscrutable actually had definite and readily intelligible causes. The main reason why these causes have been so long overlooked is that everyone is convinced that “only God knows the answer.”

Hindus venerate cows because cows are the symbol of everything that is alive. As Mary is to Christians the mother of God, the cow to Hindus is the mother of life.

An established principle of ecological analysis states that communities of organisms are adapted not to average but to extreme conditions. The relevant situation in India is the recurrent failure of the monsoon rains. To evaluate the economic significance of the anti-slaughter and anti-beef-eating taboos, we have to consider what these taboos mean in the context of periodic droughts and famine.

They don’t realize that the farmer would rather eat his cow than starve, but that he will starve if he does eat it.

In any food chain, the interposition of additional animal links results in a sharp decrease in the efficiency of food production.

The god of the ancient Hebrews went out of His way (once in the Book of Genesis and again in Leviticus) to denounce the pig as unclean, a beast that pollutes if it is tasted or touched. About 1,500 years later, Allah told His prophet Mohammed that the status of swine was to be the same for the followers of Islam.

Less commonly known are the traditions of the fanatic pig lovers. The pig-loving center of the world is located in New Guinea and the South Pacific Melanesian islands. To the village-dwelling horticultural tribes of this region, swine are holy animals that must be sacrified to the ancestors and eaten on all important occasions, such as marriages and funerals.

Before the Renaissance, the most popular was that the pig is literally a dirty animal—dirtier than others because it wallows in its own urine and eats excrement. But linking physical uncleanliness to religious abhorrence leads to inconsistencies. Cows that are kept in a confined space also splash about in their own urine and feces. And hungry cows will eat human excrement with gusto.

Maimonides said that God had intended the ban on pork as a public health measure. Swine’s flesh “has a bad and damaging effect upon the body,” wrote the rabbi. Maimonides was none too specific about the medical reasons for this opinion, but he was the emperor’s physician, and his judgment was widely respected.

In the middle of the nineteenth century, the discovery that trichinosis was caused by eating undercooked pork was interpreted as a precise verification of the wisdom of Maimonides. Reform-minded Jews rejoiced in the rational substratum of the biblical codes and promptly renounced the taboo on pork. If properly cooked, pork is not a menace to public health, and so its consumption cannot be offensive to God.

The pig is a vector for human disease, but so are other domestic animals freely consumed by Moslems and Jews. For example, undercooked beef is a source of parasites, notably tapeworms, which can grow to a length of sixteen to twenty feet within a man’s intestines, induce severe anemia, and lower resistance to other infectious diseases. Cattle, goats, and sheep are also vectors for brucellosis, a common bacterial infection in underdeveloped countries that is accompanied by fever, chills, sweats, weakness, pain, and aches. The most dangerous form is Brucellosis melitensis, transmitted by goats

...more

Faced with these contradictions, most Jewish and Moslem theologians have abandoned the search for a naturalistic basis of pig hatred. A frankly mystical stance has recently gained favor, in which the grace afforded by conformity to dietary taboos is said to depend upon not knowing exactly what Jahweh had in mind and in not trying to find out.

I think that the Bible and the Koran condemned the pig because pig farming was a threat to the integrity of the basic cultural and natural ecosystems of the Middle East.

The pig, however, is primarily a creature of forests and shaded riverbanks. Although it is omnivorous, its best weight gain is from food low in cellulose—nuts, fruits, tubers, and especially grains, making it a direct competitor of man.

So there is some truth to the theory that the religious uncleanliness of the pig rests upon actual physical dirtiness. Only it is not in the nature of the pig to be dirty everywhere; rather it is in the nature of the hot, arid habitat of the Middle East to make the pig maximally dependent upon the cooling effect of its own excrement.

As in the case of the beef-eating taboo, the greater the temptation, the greater the need for divine interdiction. This relationship is generally accepted as suitable for explaining why the gods are always so interested in combating sexual temptations such as incest and adultery.

Taboos also have social functions, such as helping people to think of themselves as a distinctive community. This function is well served by the modern observance of dietary rules among Moslems and Jews outside of their Middle Eastern homelands.

Primitive peoples go to war because they lack alternative solutions to certain problems—alternative solutions that would involve less suffering and fewer premature deaths.