More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

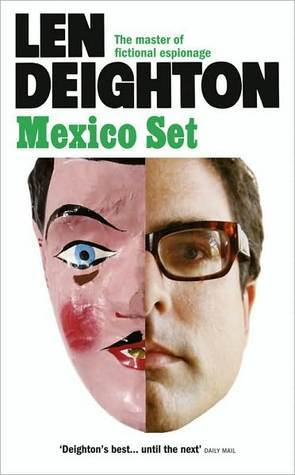

Berlin Game with its dénouement set the scene. After that Mexico Set used arguments, anger and confidences to reveal new sides of the characters and their shifting attitudes to each other. Many important characters arrive in subsequent volumes but by the end of this book all the stars are on the stage. Yet in this book – and I know this is going to sound corny – Mexico is the star. It is a wonderful country, its cruel landscape tormented by its amazing weather patterns.

most writers take manners and gestures and other bits and pieces from the

people they meet, they steal slices from the landscape, relive the pain and joy of their experience. In this way the writer pushes beyond reality in pursuit of some sort of truth. Len Deighton, 2010

flourishing his newspapers with the controlled abandon of a fan dancer. ‘Six Face Firing Squad’; the headlines were huge and shiny black. ‘Hurricane Threatens Veracruz.’ A smudgy photo of street fighting in San Salvador covered the whole front of a tabloid.

six lanes of traffic crawling along the Insurgentes halted, and more newsboys danced into the road, together with a woman selling flowers and a kid with lottery tickets trailing from a roll like toilet paper.

It was very hot. I opened the window but the sudden stink of diesel fumes made me close it again. I held my hand against the air-conditioning outlet but the air was warm. Again the fire-eater blew a huge orange balloon of flame into the air.

In any town north of the border this factory-fresh car would not have drawn a second glance. But Mexico City is the place old cars go to die. Most of those around us were dented and rusty, or they were crudely repainted in bright primary colours.

Dicky Cruyer was a curious mixture of scholarship and ruthless ambition, but he was insensitive, and this was often his undoing. His insensitivity to people, place and atmosphere could make him seem a clown instead of the cool sophisticate that was his own image of himself.

‘Muy complicado,’

‘Muy bloody complicado,’

some broken pottery figurines that a handwritten notice said were ancient Olmec.

Dicky passed it to me and walked on. I put it back on the ground with the other junk. I had too many broken fragments in my life already.

carnitas?’ ‘Stewed pork. He’s serving it on chicharrones: pork crackling. You eat the meat, then eat the plate.

Dicky could always surprise me. Just as I had decided he was the archetypal gringo tourist, he wanted to have lunch at a fonda.

two-stroke motorcycles and cars with broken mufflers and giant trucks – some so carefully painted up that every bolt-head, rivet and wheel-nut was picked out in different colours. Here on the city’s outskirts, the wide boulevard was lined with a chaos of broken walls, goats grazing on waste ground, adobe huts, rubbish tips, crudely painted shop-fronts in primary colours and corrugated-iron fences defaced with political slogans and ribaldry.

she still had that fundamental insecurity that one bout of poverty can inflict for a lifetime, and no amount of money remedy.

she showed no great interest in the plight of the hungry. And like so many poor people she had only contempt for socialism in any of its various forms, for

it is only the rich and guilty who can afford the subtle delights of egalitarian philosophies.

she’d inherited a nostalgia for a Germany of long ago. It was a Protestant Germany of aristocrats and Handküsse, silvery Zeppelins and student duels. It was a kultiviertes Germany of music, industry, science and literature; an imperial Germany ruled from the great cosmopolitan city of Berlin by efficient, incorruptible Prussians. It was a Germany she’d never seen; a Germany that had never existed.

melody everyone in Mexico knows, and quietly sang: Life is worth nothing, life is worth nothing, It always starts with crying and with crying ends. And that’s why, in this world, life is worth nothing.

Below us the guitar player sang: … Only the winner is respected. That’s why life is worth nothing in Guanajuato …

And yet, for all that, Stinnes had the quick intelligent eyes and tough self-confidence that

makes a man attractive to his fellow humans.

I poured myself a good measure of malt whisky from the bottle Biedermann had put aside for me and sipped it neat. I never really trust drinking water anywhere but Scotland; and I’ve never been to Scotland.

had the feeling he believed me and was proud to be starred by London. This was probably the right way to tackle him. It would be like a love affair; and Stinnes had reached that dangerous age when a man was only susceptible to an innocent little cutie or to an experienced floozy. And the stock-in-trade of both was flattery.

While eating my sardines I opened the stack of mail. Apart from bills for gas, electricity and wine, most of the mail was coloured advertising brochures; head waiters leered at credit cards, famous chefs offered a ‘library’ of cookbooks, pigskin wallets came free with magazine subscriptions, and there was a chance to hear all the Beethoven symphonies as I’d never heard them before.

Kimber-Hutchinson’s silver Rolls and his wife’s Jaguar. The Kimber-Hutchinsons wouldn’t have a foreign car. It wasn’t simply a matter of patriotism, the old man once told me; it would upset some of his customers. Poor fellow, he needed handmade shoes because of his ‘awkward feet’ and Savile Row suits because he wasn’t lucky enough to have the figure for ready-made ones. Cheap wine played havoc with his stomach so he drank expensive ones, and because he couldn’t fit into economy-size airline seats he was forced to go everywhere first class. Poor David, he envied people like me,

a large wooden rostrum that was said to have come from the Paris studio of Maillol, a sculptor who’d devoted his life to loving portrayals of the female nude. I’d once asked David what he used it for but got only the vaguest of answers.

It was rather as if he’d arranged things so that I would see him tracing his pictures. Perhaps he thought I would admire such acquired trickery more than mere talent. A man could not take credit for talent in the way he could for cunning.

It’s all tricks, you know. A Royal Academy painter admitted that to me once. Painting is just learning a set of tricks, just like playing the stock exchange.’

You don’t want to go to the first people you happen upon. Too many Jews in that line of business.’ A smile. ‘Oh, I forgot, you like Jews, don’t you?’ ‘No more than I like Scotsmen or Saudi Arabians. But I always suspect that whatever is being done to Jews this week

is likely to be done to me next week.

don’t go reporting Fiona’s Porsche as stolen. I sent my chauffeur to get it and it will be advertised for sale in next week’s Sunday Times. Better to get rid of it. Too many unhappy memories for you to want to use it. I knew that.’ ‘Thanks, David,’ I said. ‘You think of everything.’ ‘I do but try,’ he said.

‘You’re late,’ he said. ‘Damned late.’ ‘Yes, I am,’ I said. ‘Do I rate an explanation?’ ‘I was having this wonderful dream, Bret. I dreamed I was working for this nice man who couldn’t tell the time.’

George hates me. He’s just looking for some way to get rid of me so that he can go off with someone else.’ ‘Does George have someone else? Does he have affairs?’ ‘How can I be sure? Sex is like crime. Only one per cent motivation and ninety-nine per cent opportunity.’ She drank some wine. ‘I can’t blame him, can I? I’ve been the worst wife any man ever had. George always wanted children.’

didn’t want to admit, even to myself, that I was frightened. But that image of MacKenzie kept blurring into an image of myself, and my guilt was turning into fear. For fear is so unwelcome that it comes only in disguise, and guilt is its favourite one.

room I heard one of her favourite records playing. It was scratchy and muffled. … No one here can love and understand me, Oh what hard-luck stories they all hand me …

Lisl’s record started again. Pack up all my cares and woe. Here I go, singing low, Bye-bye, blackbird …

have the time,’ I said, ‘and you have the brandy.’ ‘I thought you were going to say: I have the time if you have the inclination, as Big Ben said to the leaning tower of Pisa.

Her record was still playing and I could imagine her propped up amid a dozen lace pillows nodding her head to the music: Make my bed and light the light, I’ll arrive late tonight. Blackbird, bye-bye.

‘Two more Pilsener,’ Werner called to Konrad. ‘And my friend will have a schnapps with his.’ ‘Just to clean the fish from my fingers,’ I said. The boy smiled. It was an old German custom to offer schnapps with the eel and use the final drain of it to clean the fingers. But like lots of old German

customs it was now conveniently discontinued.

our Pinkel and kale, a casserole dish of sausage and greens, with its wonderful smell of smoked bacon and onions. And, having decided that I was a connoisseur of fine sausage, his mother sent a small extra plate with a sample of the Kochwurst and Brägenwurst.

birthday party were eating a special order of Schlesisches Himmelreich. This particular ‘Silesian paradise’ was a pork stew flavoured with dried fruit and hot spices. There was a cheer when the stew, in its big brown pot, first arrived. And another cheer for the bread dumplings that followed soon after.

toast for Konrad’s mother who every year cooked this fine meal of Silesian favourites.

‘Our Germany has become little more than a gathering place for refugees,’ said Werner. ‘Zena’s family are just like them. They have these big family reunions and talk about the old times. They talk about the farm as if they left only yesterday.

It’s another world, Bernie. We’re big-city kids. People from the country are different from us, and these Germans from the eastern lands knew a life we can’t even guess at.’

Then they all drank to Goethe.

‘I never feel more English than when I hear someone quoting your great German poets.’

“Employ each hour which so quickly glides away …” So far, so good. But then