More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

August 7 - August 16, 2018

Summarizing, from the late 1940s, the United States supported the French war of conquest; overturned the political settlement arranged at Geneva in 1954; established a terrorist client regime in the southern section of the country divided by foreign (i.e., U.S.) force; moved on to open aggression against South Vietnam by 1962 and worked desperately to prevent the political settlement sought by Vietnamese on all sides; and then invaded outright in 1965, initiating an air and ground war that devastated Indochina. Throughout this period, the media presented the U.S. intervention entirely within

...more

The whole village had turned on the Americans, so the whole village was being destroyed,”

Attribution of the American failure by the public to “treason” or “lack of American will” caused by the failure of the media to support our just cause with sufficient fervor is, therefore, “hardly surprising.”93 This may well explain why the public has apparently been willing to accept the tales about media treachery. But among the educated elites, the explanation may lie elsewhere: in a totalitarian cast of mind that regards even the actual level of media subservience to the state as inadequate and a threat to order and privilege by the “forces of anarchy … on the march.”

“The Gulf of Tonkin incident,” Hallin observes, “was a classic of Cold War news management.… On virtually every important point, the reporting of the two Gulf of Tonkin incidents … was either misleading or simply false”—and

In the Orwellian world of American journalism, the attempt to seek a political settlement by peaceful means is the use of “military force,” and the use of military force by the United States to block a political settlement is a noble action in defense of the “guiding principle” that the use of military force is illegitimate.

The primary task facing the ideological institutions in the postwar period was to convince the errant public that the war was “less a moral crime than the thunderously stupid military blunder of throwing half a million ground troops into an unwinnable war,” as the respected New York Times war correspondent Homer Bigart explained, while chastising Gloria Emerson for her unwillingness to adopt this properly moderate view.

No doubt one could find similar complaints in the Nazi press about the Balkans.

The massacre of innocents is a problem only among emotional or irresponsible types, or among the “aging adolescents on college faculties who found it rejuvenating to play ‘revolution.’ ” 171 Decent and respectable people remain silent and obedient, devoting themselves to personal gain, concerned only that we too might ultimately face unacceptable threat—a stance not without historical precedent.

The New York Times writes sardonically of the “ignorance” of the American people, only 60 percent of whom are aware that the United States “sided with South Vietnam”—as Nazi Germany sided with France, as the USSR now sides with Afghanistan.

Postwar U.S. policy has been designed to ensure that the victory is maintained by maximizing suffering and oppression in Indochina, which then evokes further gloating here.

These reports of terrible destruction were repeatedly brought to the attention of the media, but ignored or, more accurately, suppressed. Later described as “secret bombings” in an “executive war,” the U.S. attack was indeed “secret,” not simply because of government duplicity as charged but because of press complicity.

The New York Times reviewed the war in Laos at the war’s end, concluding that 350,000 people had been killed, over a tenth of the population, with another tenth uprooted in this “fratricidal strife that was increased to tragic proportions by warring outsiders.”

The issue of U.S. bombing of Cambodia did arise during the Watergate hearings, but the primary concern there was the failure to notify Congress.

In his study of “Cambodia, Holocaust and Modern Conscience,” Shawcross muses on the relative “silence” of the West in the face of Khmer Rouge atrocities. The facts are radically different, but the idea that the West ignores Communist atrocities while agonizing over its own is far more appealing to the Western conscience.

But Shawcross and others who are deeply offended by our challenge to the right to lie in the service of one’s favored state understand very well that charges against dissident opinion require no evidence and that ideologically useful accusations will stand merely on the basis of endless repetition, however ludicrous they may be—even the claim that the American left silenced the entire West during the Pol Pot period.

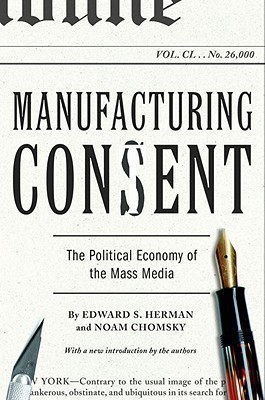

In contrast to the standard conception of the media as cantankerous, obstinate, and ubiquitous in their search for truth and their independence of authority, we have spelled out and applied a propaganda model that indeed sees the media as serving a “societal purpose,” but not that of enabling the public to assert meaningful control over the political process by providing them with the information needed for the intelligent discharge of political responsibilities. On the contrary, a propaganda model suggests that the “societal purpose” of the media is to inculcate and defend the economic,

...more

The media serve this purpose in many ways: through selection of topics, distribution of concerns, framing of issues, filtering of information, emphasis and tone, and by keeping debate within the bounds of acceptable premises.

History has been kind enough to contrive for us a “controlled experiment” to determine just what was at stake during the Watergate period, when the confrontational stance of the media reached its peak. The answer is clear and precise: powerful groups are capable of defending themselves, not surprisingly; and by media standards, it is a scandal when their position and rights are threatened. By contrast, as long as illegalities and violations of democratic substance are confined to marginal groups or distant victims of U.S. military attack, or result in a diffused cost imposed on the general

...more

It was a scandal when the Reagan administration was found to have violated congressional prerogatives during the Iran-contra affair, but not when it dismissed with contempt the judgment of the International Court of Justice that the United States was engaged in the “unlawful use of force” and violation of treaties—that is, violation of the supreme law of the land and customary international law—in its attack against Nicaragua.

As we have stressed throughout this book, the U.S. media do not function in the manner of the propaganda system of a totalitarian state. Rather, they permit—indeed, encourage—spirited debate, criticism, and dissent, as long as these remain faithfully within the system of presuppositions and principles that constitute an elite consensus, a system so powerful as to be internalized largely without awareness.

A propaganda model has a certain initial plausibility on guided free-market assumptions that are not particularly controversial. In essence, the private media are major corporations selling a product (readers and audiences) to other businesses (advertisers). The national media typically target and serve elite opinion, groups that, on the one hand, provide an optimal “profile” for advertising purposes, and, on the other, play a role in decision-making in the private and public spheres. The national media would be failing to meet their elite audience’s needs if they did not present a tolerably

...more

In the former category, the humanity and professional integrity of journalists often leads them in directions that are unacceptable in the ideological institutions, and one should not underestimate the psychological burden of suppressing obvious truths and maintaining the required doctrines of benevolence (possibly gone awry), inexplicable error, good intentions, injured innocence, and so on, in the face of overwhelming evidence incompatible with these patriotic premises. The resulting tensions sometimes find limited expression, but more often they are suppressed either consciously or

...more

In the category of supportive factors, we find, first of all, elemental patriotism, the overwhelming wish to think well of ourselves, our institutions, and our leaders. We see ourselves as basically good and decent in personal life, so it must be that our institutions function in accordance with the same benevolent intent, an argument that is often persuasive even though it is a transparent non sequitur. The patriotic premise is reinforced by the belief that “we the people” rule, a central principle of the system of indoctrination from early childhood, but also one with little merit, as an

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The technical structure of the media virtually compels adherence to conventional thoughts; nothing else can be expressed between two commercials, or in seven hundred words, without the appearance of absurdity that is difficult to avoid when one is challenging familiar doctrine with no opportunity to develop facts or argument.