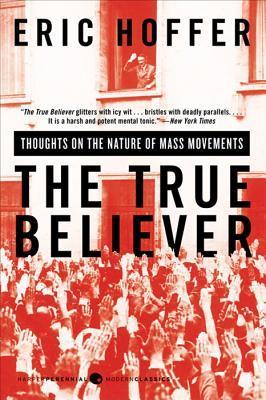

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Christianity, too, when after the conflicts and dissensions of the first few centuries it crystallized into an authoritarian church, was a patchwork of old and new and of borrowings from friend and foe. It patterned its hierarchy after the bureaucracy of the Roman Empire, adopted portions of the antique ritual, developed the institution of an absolute leader and used every means to absorb all existent elements of life and power.

No mass movement, however sublime its faith and worthy its purpose, can be good if its active phase is overlong, and, particularly, if it is continued after the movement is in undisputed possession of power.

Such mass movements as we consider more or less beneficent—the Reformation, the Puritan, French and American Revolutions, and many of the nationalist movements of the past hundred years—had active phases which were relatively short, though while they lasted they bore, to a greater or lesser degree, the imprint of the fanatic.

The mass movement leader who benefits his people and humanity knows not only how to start a movement, but, like Gand...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

It is not the idealism and the fervor of the movement which are the cause of any cultural renascence which may follow it, but rather the abrupt relaxation of collective discipline and the liberation of the individual from the stifling atmosphere of blind faith and the disdain of his self and the present. Sometimes the craving to fill the void left by the lost or deserted holy cause becomes a creative impulse.

They had not an inkling that the atmosphere of an active movement cripples or stifles the creative spirit. Milton, who in 1640 was a poet of great promise, with a draft of Paradise Lost in his pocket, spent twenty sterile years of pamphlet writing while he was up to his neck in the “sea of noises and hoarse disputes”5 which was the Puritan Revolution. With the Revolution dead and himself in disgrace, he produced Paradise Lost, Paradise Regained and Samson Agonistes.

The blindness of the fanatic is a source of strength (he sees no obstacles), but it is the cause of intellectual sterility and emotional monotony.

Actually, if there were no free societies outside the Communist orbit, they might have found it necessary to establish them by ukase.

“The Germans,” she said, “are vigorously submissive. They employ philosophical reasonings to explain what is the least philosophic thing in the world, respect for force and the fear which transforms that respect into admiration.”

The manner in which a mass movement starts out can also have some effect on the duration and mode of termination of the active phase of the movement. When we see the Reformation, the Puritan, American and French revolutions and many of the nationalist uprisings terminate, after a relatively short active phase, in a social order marked by increased individual liberty, we are witnessing the realization of moods and examples which characterized the earliest days of these movements.

Only a goal which lends itself to continued perfection can keep a nation potentially virile even though its desires are continually fulfilled. The goal need not be sublime. The gross ideal of an ever-rising standard of living has kept this nation fairly virile. England’s ideal of the country gentleman and France’s ideal of the retired rentier are concrete and limited.