More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

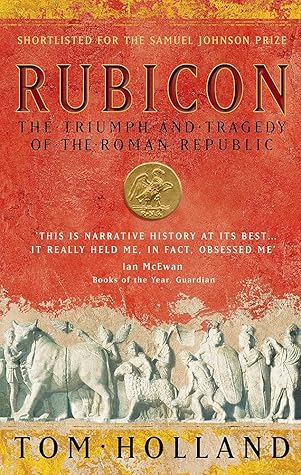

Tom Holland

Read between

November 16 - December 4, 2020

By the first century BC, there was only one free city left, and that was Rome herself. And then Caesar crossed the Rubicon, the Republic imploded, and none was left at all.

Only a few prefer liberty – the majority seek nothing more than fair masters.

The Romans, being a people as practical as they were devout, had no patience with fatalism. They were interested in knowing the future only because they believed that it could then better be kept at bay.

The Romans recognised no difference between moral excellence and reputation, having the same word, honestas, for both. The approval of the entire city was the ultimate, the only, test of worth.

Praise was what every citizen most desired – just as public shame was his ultimate dread.

To place personal honour above the interests of the entire community was the behaviour of a barbarian – or worse yet, a king.

The Romans killed to inspire terror, not in a savage frenzy but as the disciplined components of a fighting machine.

A decade and a half after Cannae Hannibal faced another Roman army, but this time on African soil. He was defeated. Carthage no longer had the manpower to continue the struggle, and when her conqueror’s terms were delivered, Hannibal advised his compatriots to accept them. Unlike the Republic after Cannae, he preferred not to risk his city’s obliteration. Despite this, the Romans never forgot that in Hannibal, in the scale of his exertions, in the scope of his ambition, they had met the enemy who was most like themselves. Centuries later statues of him were still to be found standing in Rome.

Of all Rome’s seven hills, however, the Palatine was the most exclusive by far. Here the city’s elite chose to cluster. Only the very, very rich could afford the prices. Yet, incongruously, there on the world’s most expensive real estate stood a shepherd’s hut made of reeds. The reeds might dry and fall away, but they would always be replaced, so that the hut never seemed to alter. It was the ultimate triumph of Roman conservationism – the childhood home of Romulus, Rome’s first king, and Remus, his twin.

In practice as well as principle the Republic was savagely meritocratic. Indeed, this, to the Romans, was what liberty meant.

Yet the constitution was a hall of mirrors. Alter the angle of inspection, and popular sovereignty might easily take on the appearance of something very different. Foreigners were not alone in being puzzled by this shape-shifting quality of the Republic: ‘the Romans themselves’, a Greek analyst observed, ‘find it impossible to state for sure whether the system is an aristocracy, a democracy, or a monarchy’.17

It was two brothers of impeccable breeding, Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus, who finally made the fateful attempt. First Tiberius, in 133 BC, and then Gaius, ten years later, used their tribunates to push for reforms in favour of the poor.

It was said that even as Scipio watched the flames lap at the crumbling walls of the great city, he had wept. In the destruction of Rome’s deadliest enemy he could see, like the Sibyl, the baneful power of the workings of Fate.

What was the Republic, after all, if not a partnership between Senate and people – ‘Senatus Populusque Romanus’, as the formula put it? Stamped on the smallest coins, inscribed on the pediments of the vastest temples, the abbreviation of this phrase could be seen everywhere, splendid shorthand for the majesty of the Roman constitution – ‘SPQR’.

As long as the effete monarchs of Asia sent their embassies crawling to learn the every whim of the Senate, as long as the desert nomads of Africa reined in their savagery at the merest frown of a legionary commander, as long as the wild barbarians of Gaul dreaded to challenge the unconquerable might of the Republic, then Rome was content. Respect was all the tribute she demanded and required.

So it was that in 123, after a decade of agitation, Gaius Gracchus finally succeeded in pushing through a fateful law. By its terms, Pergamum was at last subjected to organised taxation. The lid of the honeypot was now well and truly off.

Cities were no longer sacked, they were bled to death instead.

Measurements of lead in the ice of Greenland’s glaciers, which show a staggering increase in concentration during this period, bear witness to the volumes of poisonous smoke they belched out.8 The ore being smelted was silver: it has been estimated that for every ton of silver extracted over ten thousand tons of rock had to be quarried. It has also been estimated that by the early first century BC, the Roman mint was using fifty tons of silver each year.

Their most notorious victim was Rutilius Rufus, a provincial administrator celebrated for his rectitude who had sought to defend his subjects against the tax-collectors, and who in 92 BC was brought to trial before a jury stuffed with supporters of the publicani. Big business had successfully oiled the workings of the court: the charge – selected with deliberate effrontery – was extortion.

Looking to widen their activities, Roman business interests began casting greedy eyes on Pontus, a kingdom on the Black Sea coast in the north of what is now Turkey. In the summer of 89 the Roman commissioner in Asia, Manius Aquillius, trumped up an excuse for an invasion.

Eighty thousand men, women and children were said to have been killed on that single, deadly night.10 As a blow to the Roman economy, this was calculated and devastating; but as a blow to Roman prestige it was far worse.

‘War-mongers against every nation, people and king under the sun, the Romans have only one abiding motive – greed, deep-seated, for empire and riches.’11 This had been the verdict of Mithridates on the Republic and now, in the person of her legate in Asia, he exacted symbolic justice. Manius Aquillius choked to death on gold.

All along, the rickety new state had never been anything more than second best to the Italians’ real ambition – enrolment as citizens of Rome.

In 91 BC a proposal to enfranchise the Italians had been abandoned amid rioting and violent demonstrations, and its proposer, retiring in dudgeon to his home, had been stabbed to death in the twilight gloom of his portico. The murderer was never found, but the Italian leaders had certainly known who to blame.

The massacre at Asculum had heralded the revolt, and it was news from Asculum again that enabled the Romans to celebrate their first decisive victory of the war. The triumphant general had been Gnaeus Pompeius ‘Strabo’,

Accordingly, in October 90 BC a bill was proposed and passed. By its provisions all the Italian communities that had stayed loyal were granted Roman citizenship immediately, and the rebels were promised it in due course if they would only lay down their arms.

In Rome, by contrast, in senatorial circles the prospect of a war with Mithridates was greeted with open relish.

One man in particular regarded the command as his by right. Marius had long had his eye on a war with Mithridates. Ten years previously he had travelled to Asia and confronted the King face to face, telling him with the bluntness of a man spoiling for a fight either to be stronger than Rome or to obey her commands.

The events and sources are murky, but it is possible that there is an explanation here for Aquillius’ otherwise seemingly cavalier attitude towards Rome’s security in the East, at a time when, back in Italy, she was fighting for her life. He had been aiming to provide his patron with a glorious Asian war.

An Eastern command was a prize so rich that no one, not even Marius, could take it for granted. There were others, hungry and ambitious, who wanted it too. Just how badly would soon become clear.

As a result, the fate of a Roman who had tasted the sweetness of glory might often be a consuming restlessness, the gnawing, unappeasable agony of an addict. So it was that Marius, even in his sixties, and with countless honours to his name, still dreamed of beating his rivals to the command of the war against Mithridates. And so it was that Sulla, even were he to win the consulship, would continue to be taunted by the example of his old commander. Just as Marius’ villa outshone all others on the Campanian coast, so too did his prestige outrank that of any other former consul. Most men were

...more

Although much reduced from the numbers Sulla had commanded the previous summer, they nevertheless represented a menacing concentration of fighting power. Only the legions of Pompeius Strabo, busy mopping up rebels on the other side of Italy, could hope to rival them. Marius, back in Rome, had no legions whatsoever. The maths was simple. Why, then, had Marius failed to work it out, and how could so hardened an operator have chosen to drive his great rival into a corner where there were six battle-hardened legions ready to hand? Clearly, the prospect that Sulla might come out of it fighting had

...more

As flames began to crackle and spread down the line of the city’s highways Sulla himself rode along the greatest of them all, the via Sacra, into the very heart of Rome. Marius and Sulpicius, after a futile attempt to raise the city’s slaves, had already fled. Everywhere, mail-clad guards took up their new posts. Swords and armour were worn outside the Senate House. The unthinkable had happened. A general had made himself the master of Rome.

Strabo welcomed the man come to take his place with a menacing politeness. He presented Rufus to the troops, then absented himself from the camp – on business, he claimed. The next day Rufus celebrated his new command by performing a sacrifice. A gang of soldiers clustered round him where he stood by the altar, and as he raised the sacrificial knife they seized him and struck him down, ‘as though he were the sacrificial offering himself’.4 Strabo, claiming to be outraged, hurried back to the camp but took no action against his murderous troops. Inevitably, the rumours that had dogged Sulla in

...more

The Republic, in the eyes of its citizens, was something much more than a mere constitution, a political order to be toppled or repealed. Instead, hallowed by that most sacred of Roman concepts, tradition, it provided a complete pattern of existence for all those who shared in it. To be a citizen was to know that one was free – ‘and that the Roman people should ever not be free is contrary to all the laws of heaven’.* Such certainty suffused every citizen’s sense of himself. Far from expiring with Sulla’s march on Rome, respect for the Republic’s laws and institutions endured because they were

...more

In an economy run by and for the super-rich the wealthier a minority of citizens became, the more the resentments of the majority seethed. This was true of every society in the ancient world, but in Athens – the birthplace of democracy – perhaps uniquely so.

Athens being Athens, the revolution was led by a philosopher, one Aristion, an old sparring partner of Posidonius who did not share his rival’s positive perspective on Rome. With Italy riven by war, however, and an alliance with the all-conquering Mithridates in the bag, Aristion did not expect too much trouble from the Romans. To the ecstatic Athenians, independence and democracy alike appeared secured. Then, in the spring of 87, Sulla landed in Greece.

Soon afterwards Sulla held a summit with Mithridates himself. Both men had good reason to come to an agreement. Mithridates, knowing that the game was over, was desperate to keep hold of his kingdom. Sulla, nervous of his enemies back in Italy, was eager to head home. In return for accepting controls on his offensive capability and the surrender of all the territory he had conquered, the murderer of eighty thousand Italians was rewarded by Sulla with a peck on his cheek. No one had ever emerged so unscathed from a war with the Republic before. Beaten he may have been, but Mithridates still sat

...more

As he pointed out proudly in a letter to the Senate, in barely three years he had won back all the territory annexed by Mithridates. Greece and Asia once again acknowledged the sway of Rome. Or so it suited Sulla to pretend. In fact, he no longer represented the Republic. The government he had established back in Rome had collapsed. Sulla himself had been condemned to death in absentia, his property razed, his family forced to flee.

Back in the distant days of the kings, excavators digging the temple’s foundations had found a human head. Augurers, summoned to interpret this wonder, had explained that it foretold Rome’s future as the head of the world. Who could doubt, then, that it was Jupiter who had guided the Republic to its greatness?

Approaching the tent of the novice general, he dismounted from his horse. A young man stood waiting, his golden hair swept up in a quiff, his profile posed to look like Alexander’s. He hailed Sulla as ‘Imperator’ – ‘General’ – and Sulla then greeted him as ‘Imperator’ in turn. This was an honour that it usually took even the most accomplished soldier many years to earn. Gnaeus Pompeius – ‘Pompey’ – was barely twenty-three.

The Samnites, shadow-boxing with Sulla, first attempted to march to Marius’ relief, but then, with the sudden realisation that Rome lay unprotected in their rear, swung round abruptly and marched on the capital. Sulla, taken by surprise, pursued them at frantic speed. As the Samnites appeared within sight of Rome’s walls, their commander ordered them to wipe out the city. ‘Do you think that these wolves who have preyed so terribly upon the freedoms of Italy will ever vanish until the forest that shelters them has been destroyed?’3 he cried.

The bloodbath of the Colline Gate was decisive. His enemies had no more armies left in Italy with which to continue the war. As the Samnite prisoners began to be rounded up Sulla was the absolute, unquestioned master of Rome.

Citizens assembled to vote for the consuls in the same way that their earliest ancestors had massed to go to war. Just as in the days of the kings, a military trumpet would be blown at daybreak to summon them to the Campus. A red flag would flutter on the Janiculum Hill beyond the Tiber, signalling that no enemies could be seen. The citizens would then line up as though for battle, with the richest at the front and the poorest at the rear. This meant that it was always the senior classes who were the first to pass into the Ovile. Nor was that their only privilege. So heavily weighted were

...more

The symbolism was shocking and obvious: Sulla rarely made any gesture without a fine calculation of its effect. By washing the Villa Publica with blood he had given dramatic notice of the surgery he was planning to perform on the Republic. If the census were illegitimate, then so too were the hierarchies of status and prestige that it had affirmed. The ancient foundations of the state were unstable, on the verge of collapse. Sulla, god-sent, would perform the repairs, no matter how much bloodshed the task might require.

The pauper who had once been forced to doss in squalid flop-houses was now richer than any Roman in history. It so happened that during the course of the proscriptions a senator who had been condemned to death was found hiding in the house of one of his former slaves. The freedman was duly brought before Sulla to be condemned. The two men recognised each other at once. Both, long before, had shared lodgings in the same apartment block, and the freedman, even as he was hauled away to his execution, yelled at Sulla that there had once been little difference between them. He meant it as a taunt,

...more

Unlike the consulship, split as it was between two citizens of equal rank, the unified powers of the dictatorship were inherently offensive to Republican ideals. This was why the office had fallen into abeyance. Even back in the dark days of the war against Hannibal, citizens had been appointed to it only for very short, fixed periods. Like unmixed wine, the dictatorship had a taste that was intoxicating and perilous. Sulla, however, who enjoyed alcohol and power equally, was proud of his head for both. He refused to accept a limit on his term of office. Instead, he was to remain dictator

...more

It was an irony that shadowed the entire programme of his reforms. Sulla’s task as dictator was to ensure that in the future no one would ever again do as he had done and lead an army on Rome. Yet it is doubtful whether Sulla himself would have regarded this as a paradox.

From quaestorship to praetorship to consulship, only a single path to power, and no short cuts. The deliberate effect of this legislation was to place a premium on middle age. In this it accorded with fundamental Roman instincts.

To ensure that tribunes could never again propose bills attacking a consul, as Sulpicius had done, Sulla barred them from proposing bills altogether. To prevent the tribunate from attracting ambitious trouble-makers in the future, he throttled it of all potential to advance a career. With carefully nuanced malice, Sulla banned anyone who had held the office from seeking further magistracies. Quaestors and praetors might dream of the consulship, but not tribunes, not any more. Their office was to be a rung on a ladder leading nowhere. Revenge, as ever with Sulla, was sweet.