More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Between ourselves, though, Dhai Ma and I agreed that Gandhari’s sacrifice wasn’t particularly intelligent. “If my husband couldn’t see, I’d make doubly sure to keep my own eyes open,” I said, “so that I could report everything that was going on to him.” Dhai Ma was of a different opinion. “Maybe the thought of marrying a blind man disgusted her—but being a princess she couldn’t get out of the match. Maybe she did this so she wouldn’t have to look at him every single day of her life.”

Perhaps strong women tended to have unhappy marriages? The idea troubled me.)

A princess has no privacy.

Each morning when they woke—in the same town, or kingdoms apart—their first thoughts would be of each other. In anger and regret, they’d both wish she’d had the courage to choose another way.

Karna’s hand tightens around his bow. Arjun! he calls. But Arjun has already turned his back on him and is walking away. Karna stares after him. It is the supreme insult—one for which he’ll never forgive Arjun. From this moment on, they will be arch-enemies.

And Karna will hold himself very straight and reply, When the time comes, I will do so for you, my liege and my friend—or I will die trying.

“Ah, forgiveness,” Dhri said. “It’s a virtue that eludes even the great. Isn’t our own existence a proof of that?”

No matter how skilled they were at battle, ultimately it would not help them because they were forever defeated by their conscience. What cruel god fashioned the net of their minds this way, so they could never escape it? And what traps had he set up for me?

When I stepped into the wedding hall, there was complete, immediate silence. As though I were a sword that had severed, simultaneously, each vocal cord.

I went, but all the way loyalty and desire dueled inside me. If Arjun wasn’t here, what right did Krishna and Dhri have to insist that I not choose Karna?

In the face of that question, Karna was silenced. Defeated, head bowed in shame, he left the marriage hall. But he never forgot the humiliation of that moment in full sight of all the kings of Bharat. And when the time came for him to repay the haughty princess of Panchaal, he did so a hundredfold.

Later, some would commend me for being brave enough to put the upstart son of a chariot driver in his place. Others would declare me arrogant. Caste-obsessed. They’d say I deserved every punishment I received. Still others would admire me for being true to dharma, whatever that means. But I did it only because I couldn’t bear to see my brother die.

Can our actions change our destiny? Or are they like sand piled against the breakage in a dam, merely delaying the inevitable?

When I’d stepped forward and looked into his face, there had been a light in it—call it admiration, or desire, or the wistful beginnings of love. If I’d been wiser, I might have been able to call forth that love and, in that way, deflected the danger of the moment—a moment that would turn out to be far more important than I imagined. But I was young and afraid, and my ill-chosen words (words I would regret all my life) quenched that light forever.

That was what I told myself as we walked and walked, the hot day wilting around us, the pathway of stone and thorn taking me further each moment from everything that had been familiar to me.

But I was distressed by the coldness with which my father and my potential husband discussed my options, thinking only of how these acts would benefit—or harm—them.

I can’t say I was surprised by Vyasa’s verdict. (Hadn’t his spirits threatened me with such a fate years ago?) But now that it was to become an imminent reality, I was surprised at how angry it made me feel—and how helpless.

I had no choice as to whom I slept with, and when. Like a communal drinking cup, I would be passed from hand to hand whether I wanted it or not.

My heart sank as I saw that he’d made me the target of the frustrated rage that he couldn’t express toward his brothers or his mother.

I’d never seen a man—least of all a famous warrior—shed tears.

I felt my mistrust melting in the warmth of his smile. Perhaps, I thought, I was finally going where I belonged.

Expectations are like hidden rocks in your path—all they do is trip you up.

If she’d heard me pronounce his name, she would have known how I felt. And even to her who loved me as she loved no one else, I didn’t dare reveal this dark flower that refused to be uprooted from my heart.

No matter how famous or powerful they became, my husbands would always long to be cherished. They would always yearn to feel worthy. If a person could make them feel that way, they’d bind themselves to him—or her—forever.

I thought they said, Five? Are you sure? Five! There was envy in their eyes. But I may be wrong. Maybe it was sympathy.

A well-meaning man, Dhai Ma liked to say, is more dangerous because he believes in the rightness of what he does. Give me an honest rascal any day!

“She said you were a great flame, capable of lighting our way to fame—or destroying our entire clan.”

Why should things be different now, just because I was a wife? The old restlessness from my girlhood that I’d thought I was done with—if only I could have been a man—rose in me as I watched them clap each other on the back.

But truth, when it’s being lived, is less glamorous than our imaginings.

the currents of history had finally caught me up and were dragging me headlong. How much water would I have to swallow before I came to a resting place?

It’s the best thing that could happen to you, she said.

Sometimes when he didn’t know I was watching, there was a starkness on his face, the look of a man who was consumed by jealousy and hated himself for it.

He was right. In order for a victory to occur, someone had to lose. For one person to gain his desire, many had to give up theirs.

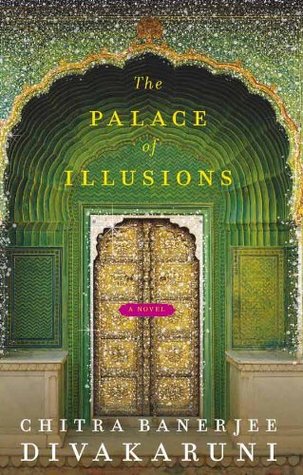

“This creation of yours that’s going to be the envy of every king in Bharat—we’ll call it the Palace of Illusions.”

“You save Maya life,” he said, “so I give you warning. Live in palace. Enjoy. But not invite anyone to come see.”

I took my place beside each of my husbands at the proper moment, and saw our pairings as movements in an elaborate dance.

If they were pearls, I was the gold wire on which they were strung. Alone, they would have scattered, each to his dusty corner.

But I thought that if lokas existed at all, good women would surely go to one where men were not allowed so that they could be finally free of male demands.

It struck me like an iron fist, the realization that if Krishna wasn’t in my life, nothing mattered. Not my husbands, not my brother, not this palace I was so proud of, not the look I longed to see in Karna’s eye.

“Now you’ve ruined that abominably expensive sari,” he said. “I’ll have to get you a new one, although it’s probably not going to be as fine. I’m a relatively minor king, after all!” I stared at him in shock, then reddened. Did he know my other thoughts, including those about Karna?

“When I thought you had died, I wanted to die, too.”

Krishna gazed into my eyes. Was it love I saw in his face? If so, it was different in kind from all the loves I knew. Or perhaps the loves I’d known had been something different, and this alone was love. It reached past my body, my thoughts, my shaking heart, into some part of me that I hadn’t known existed.

Each day they were more like ornate figureheads on a ship that had changed its course without their consent and was sailing into dangerous waters.

I’m a queen. Daughter of Drupad, sister of Dhristadyumna. Mistress of the greatest palace on earth. I can’t be gambled away like a bag of coins, or summoned to court like a dancing girl.

No one can shame you, he said, if you don’t allow it.

Their notions of honor, of loyalty toward each other, of reputation were more important to them than my suffering.

I would have thrown myself forward to save them if it had been in my power that day. I wouldn’t have cared what anyone thought. The choice they made in the moment of my need changed something in our relationship.

“A situation in itself,” he said, “is neither happy nor unhappy. It’s only your response to it that causes your sorrow.

She’s dead. Half of her died the day when everyone she had loved and counted on to save her sat without protest and watched her being shamed. The other half perished with her beloved home. But never fear. The woman who has taken her place will gouge a deeper mark into history than that naïve girl ever imagined.

“How did it feel,” I asked him later, when we lay satiated, “to touch a god?” He didn’t answer. Perhaps he was asleep. Or perhaps there is no answer to such a question. For later when I’d ask Arjun the same thing, he, too, would be silent.