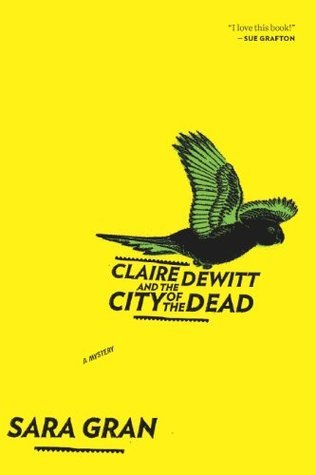

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

To let go of the self is the highest calling of the self, something that few achieve. And something that every self, whether she knows it or not, aspires to.

“The clue that can be named is not the eternal clue,” Silette wrote. “The mystery that can be named is not the eternal mystery.”

‘Be grateful for every scar life inflicts on you.’

‘Where we’re unhurt is where we are false. Where we’re wounded and healed is where our real self gets to show itself.’ That’s where you get to show who you are.”

“You can’t change anyone’s life,” she said. “You can’t erase anyone else’s karma.” “But—” I began. Constance stopped me, shaking her head. “All you can do is leave clues,” she said. “And hope that they understand, and choose to follow.”

“Mysteries exist independently of us,” Silette wrote. “A mystery lives in the ether; it floats into our world on the wind like an umbrella and lands where gravity pulls it. And all the elements around it are now rearranged into the elements of a mystery: a tightly woven lace of clues and detectives, villains and victims. Yesterday’s peaceful cottage is now a murder scene. The previously unremarkable butter knife on the counter is now an ominous weapon. The bland, unnoticed doorman is now a suspect. “Those who step into this pattern, often through no fault of their own, have no choice but to

...more

“There are moments in life that are quicksand,” Silette wrote. “A gun goes off. A levee breaks. A girl goes missing. These moments of time are different from the others. Quicksand is a dangerous place to be. We will drown there if we can’t get out. But it tricks us. It tricks us into confusing it with safety. At first, it may seem like a solid place to stay. But slowly we’re sinking. You will never move forward. Never move back. In quicksand you will slowly sink until you drown. The deeper you let yourself sink, the harder it is to claw yourself out. “These spots of quicksand are unsolved

...more

“The client exists not as a part of the whole but as an external source of power,” Silette wrote. “If the mystery is Shiva, the client is Shakti. The client initiates the descent into the mystery, but after that she is no longer needed; the detective proceeds of his own accord. The detective will more often than not solve the mystery despite the client, not because of her. “The client is the errant goat that leads Persephone to the weak spot of earth where Pluto can let her in. “No one remembers the name of the goat. Everybody remembers the name of the first detective, Persephone.”

Maybe he was part of a committee to help people remember New Orleans before and forget New Orleans now.

“Not one detective in a thousand will hear my words,” Silette wrote, “and of those, one in one hundred will understand. It is for them who I write.”

Like a lot of people who thought about suicide, Andray didn’t actually want to die. Dying was the hard part. He just wanted to be dead already.

“Of course, anyone may be saved,” Silette said in his 1978 Interview interview. “No matter the crime. What they don’t understand is that it is just like solving a crime; one must do it oneself, for one’s own reasons, each on one’s own time, and not for some stupid ideal of what the world can be or some childish notions of good and bad. The only way is to dive into oneself completely, which of course is the very last thing most of us will ever do. You must dive all the way to the bottom. Then, really, life can begin anew.”

“The detective who wishes a rapid conclusion to his case,” Silette wrote, “need do no more than examine every thing he was absolutely sure would not lead to the truth, and need only connect those facts he was entirely sure had no relation at all. Because this, for better or worse, is exactly where the truth lies—at the intersection of the forgotten and the ignored, in the neighborhood of all we have tried to forget.”

“Karma,” he said once, “is not a sentence already printed. It is a series of words the author can arrange as she chooses.”