More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

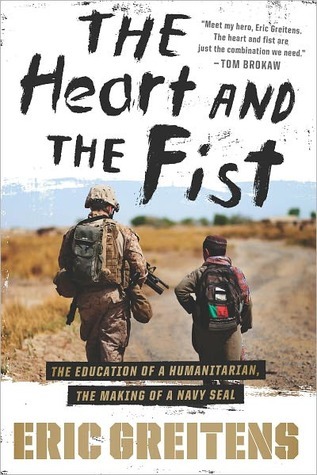

This is a book about service on the frontlines. I’ve been blessed to work with volunteers who taught art to street children in Bolivia and Marines who hunted al Qaeda terrorists in Iraq. I’ve learned from nuns who fed the destitute in Mother Teresa’s homes for the dying in India, aid workers who healed orphaned children in Rwanda, and Navy SEALs who fought in Afghanistan. As warriors, as humanitarians, they’ve taught me that without courage, compassion falters, and that without compassion, courage has no direction. They’ve shown me that it is within our power, and that the world requires of

...more

Travis Manion and two other Marines then ran up onto the roof. Travis was a recent graduate of the Naval Academy, where he’d been an outstanding wrestler. I came to know him while we patrolled the streets of Fallujah together. Travis was tough, yet he walked with a smile on his face. He was respected by his men and respected by the Iraqis. A pirated copy of a movie about the last stand of three hundred Spartan warriors had made its way to Fallujah, and Travis was drawn to the ideal of the Spartan citizen-warrior who sacrificed everything in defense of his community. He likened his mission to

...more

On the frontlines—in humanitarian crises, in wars overseas, and around some kitchen tables here at home—I’d seen that peace is more than the absence of war, and that a good life entails more than the absence of suffering. A good peace, a solid peace, a peace in which communities can flourish, can only be built when we ask ourselves and each other to be more than just good, and better than just strong. And a good life, a meaningful life, a life in which we can enjoy the world and live with purpose, can only be built if we do more than live for ourselves.

As I was talking with the students over dinner, I realized that this was the first time I had ever spoken with people who had been part of shaping history. I had watched them on TV. Now I saw that those courageous activists were very real people. Some of them liked soy sauce on their dumplings; others drank more than they ate. Some of them were unshaven, some of them joked constantly, and some had big dreams of going to America. History was alive today. It was made by people: courageous, determined, thoughtful—it was made by people my age.

Derrick Humphrey was twenty-six years old. He stood six foot two, and he had the powerful build of a tall, fast fighter. He worked construction. He had a few marks on his record from an ill-disciplined youth, and a scar across the bridge of his nose. I assumed then that the scar was from boxing; he later told me that his mother had cracked him across the face with a wooden stick for acting up as a kid.

“OK, now, here we go. Derrick, and, and both of you all, gonna get those knees high. Ready. Time.” Derrick and I started running in place in the parking lot, lifting our knees high and punching our fists every step. Earl watched his stopwatch. “Time,” he said, and then Derrick walked a short circle around the parking lot and I did the same.

It would be wrong to say that Earl taught life lessons along with boxing, because for Earl, there was no distinction to be made between life and boxing. Every action was invested with significance. How we hung the heavy bag, God’s mercy, the way a man should wrap his hands, the virtue of humility, the proper way to lace gloves, being on time, the way a teacher should love his students, the proper way to care for your equipment—these were all part of one solid and unbroken piece. Earl refused to call himself a coach. As he put it, “A coach makes you more skilled, shows you how to be better at a

...more

Earl made us say a prayer before we started every practice. He would say, “Just go on and say whatever is right for you to say,” and we would shut our eyes and say a silent prayer. I had—before boxing—never been someone who prayed on a daily basis, and it felt uncomfortable at first. But boxing is a violent discipline, and after a few days of getting cracked in the ribs, praying seemed like a sensible way to begin.

I had begun to earn the strength that comes from working through pain and it felt good.

And it was also true that a boxer who used his strength to inflict pain on the weak was less than a dog. “I wouldn’t even call ’im a dog, ’cause I have known some good, beautiful dogs in my life, and any man that goes ’round and beats up on women, beats up on children, he ain’t even as good as a dog, no sir.” God, in Earl’s view, had invested every person with strength, and it was our duty to develop that strength. “What did my Father give you muscles for? What did he give you brains for? Now look here, I may not be the strongest man on the block, not the smartest man on the street, but I know

...more

Earl rarely used the word, but his whole system of teaching and his whole way of living was built around the concept of honor. You honored God by using your time wisely, and you honored your fellow man by treating him with respect. You honored your teacher by calling him “sir,” and he honored his students by challenging them to face pain and become stronger. Earl had come to associate charity with pain, and he believed that love did its deepest work when applied to a wound.

Later, when I thought about the UN workers in Gasinci writing their letter, when I read about what had happened at Srebrenica, I realized that there was a great dividing line between all of the speeches, protests, feelings, empathy, good wishes, and words in the world, and the one thing that mattered most: protecting people through the use of force or threat of force. In situations like this, good intentions and heartfelt wishes were not enough.

The great dividing line between words and results was courageous action.

Men climbed atop the bus. Boys handed up bags and jugs and boxes to be lashed to the roof. Teenage girls with baby brothers and sisters strapped to their backs stopped at the entrance to the bus and shifted the younger children into their arms. I admired these families, if only for their stubborn will to keep going. Back at college I’d been reading about courage in my philosophy classes.

There were a number of definitions of courage, but now I was seeing it in its simplest form: you do what has to be done day after day, and you never quit.

Yet the images of refugee camps and border crossings that flooded the international broadcast media did not tell the whole story. They left an impression of desperate, downtrodden, despairing people. I quickly learned that the media traffics in tragedy, but often misses stories of strength.

I struggled with taking photographs that day. I wanted to capture their portraits, to share what I saw with others. Few Americans had seen this: Strong people. Survivors. Solid. Steadfast. I knew that these women weren’t perfect, and that it was foolish to cast someone as saintly simply because she had suffered. These women might also have been trivial and jealous and mean and small. But the enormity of their achievement outweighed their human faults. These women had suffered more than I could have ever imagined, and they still were willing to welcome me, to talk with me. After all the

...more

He lowered his voice. “They’re giving food and shelter, but they don’t have any job-training or substance-abuse programs. They keep running things this way, these people will stay homeless forever.” Just as Bruce was challenging the participants in his leadership program by bringing us to the shelter, he wanted to see the men in the shelter challenged as well. Just as Bruce respected us, he respected the homeless men, and he believed that if you respected someone, then you had to ask something of them. These men, he believed, should be involved in their own recovery.

I thought of the survivor who stood her child up for me to photograph, and as I left Rwanda I thought of the way that parents love their children. They hug them when they need love, they care for them when they are sick, heal them when they are injured. But parents also protect their children when they are threatened. Wouldn’t it be strange to find parents who would hug their children, would tend to their wounds, but wouldn’t protect them from getting hurt in the first place? Nations are not parents to the world’s people. Yet the basic fact remains: we live in a world marked by violence, and

...more

One day I stood outside a health care clinic in Rwanda as a volunteer pointed to a young girl with a deep machete scar that ran from behind her right ear across the back of her neck. We look at a scar like that—we reflect on the evil that human beings are capable of—and we are tempted to walk away from humanity altogether. But when that same child smiles at us, when that same child lets us know that she has survived and she has grown, then we have no choice. We have no choice but to go forward in the knowledge that it is within our power, and that the world requires of us—of every one of

...more

Here in Bolivia most of the kids played in bare feet, and they had as much fun as we ever had. Alone, human beings can feel hunger. Alone, we can feel cold. Alone, we can feel pain. To feel poor, however, is something we do only in comparison to others. I took off my shoes. In the home, these kids weren’t poor. Their recreation consisted of soccer, tag, a dozen other run-and-chase games, marbles in the dirt, bottle caps. In their imaginations, they turned old tires into fighter planes and cardboard boxes into candy stores.

If we want to change something, we must begin with understanding. But if we want to love something, we must begin with acceptance. The beauty of what Jason and Caroline had done was to begin with acceptance and love. Then, by virtue of their courage, their intelligence, and their compassion, they were able to change the lives of the children in their charge in a profound way. Their love was built on patience, and their faith helped them to know that they couldn’t do everything, but they did have to do what they could.

Later, in the military, I’d read briefs of well-intentioned officers who had designed “programs” to “swiftly rebuild civil society” after war, after institutional collapse. I admired their intentions, but if Bolivia taught me anything, it was that there are some things—like civil society, like character, like a child’s belief in the future—that cannot be achieved overnight. Humanitarians, warriors, scholars, and diplomats all do best when we recognize the difference between what we can fight for and what we must accept, between change that can be catalyzed and change that must be built over

...more

1 Doing humanitarian work overseas, I had come to realize that it’s not enough to fight for a better world; we also have to live lives worth fighting for. In my senior year of college I applied for a Rhodes scholarship, awarded annually to men and women who are meant to “fight the world’s fight.” Scholars are sent to graduate school at Oxford University in England, and it was at Oxford that I really began to appreciate all of life’s beauty: joy, delight, rest, love, tranquillity, peace. These are things worth fighting for, for others and for ourselves.

Amid the pleasures of Oxford life and the draw of the boxing team, I was still determined to find a pathway for humanitarian work. I wrote a dissertation on the subject. My thesis was simple: What matters for the long-term health and vitality of people who have suffered is not what they are given, but what they do. Rather than simply giving aid to children, it made sense to support children, families, and communities that were already engaged in their own recovery.

The streets were teeming with young men my age. They were all well fed (in part by United Nations support), they had access to some education, but they had no real prospects to ever leave Gaza, and in Gaza there was little work to be had. I’d learned that the classic view of “the poor” as a breeding ground for terrorists and insurgents was mistaken. Poor people, hungry people, rarely dedicate their lives to violence. They are too focused on their next meal. Revolutionaries are often middle and upper class, comfortable but frustrated people who choose violence.

After spending time in a place of such care and love, I came to understand that when we see self-righteousness it is often an expression of self-doubt and self-hatred. In a place where people are able to accept themselves, love themselves, and know that they are loved, there is no need to criticize or compare, cajole or convince. The sisters concentrated, instead, on loving their neighbors.

I had become an advocate for using power, where necessary, to protect the weak, to end ethnic cleansing, to end genocide. But as I wrote papers to make this argument and spoke at conferences, my words seemed hollow. I was really saying (in so many words) that someone else should go somewhere to do dangerous work that I thought was important. How could I ask others to put themselves in harm’s way if I hadn’t done so myself?

I’d learned that all of the best kinds of compassionate assistance, from Mother Teresa’s work with the poor to UNICEF’s work with refugee children, meant nothing if a warlord could command a militia and take control of the very place humanitarians were trying to aid. The world needs many more humanitarians than it needs warriors, but there can be none of the former without enough of the latter. I could not shake the memory of little kids in Croatia drawing chalk pictures of the homes that their families had fled at gunpoint.

I threw myself into the school. Wong and I began to take breaks every ten minutes while working on our uniforms to knock out fifteen pushups. I became the “PT Body,” the person in charge of the physical training of the class. I grew to respect Wong in particular. OCS was hard on him. He must have known that it would be hard when he signed up, but still he signed up.

I still found the underwear folding and the keep-your-sneakers-clean-for-inspection stuff ridiculous, but I began to see some of the wisdom in what the drill instructors were doing. Some of the people in my class had never been screamed at before. Now they had two trained drill instructors screaming at them and putting them through what were—for some of them—demanding physical exercises while they were forced to recall answers to essential military questions. This did not necessarily approximate the stress of what they would experience as ship commanders, but it did begin to teach the

...more

Uncontrolled fear rots the mind and impairs the body. Navy officers have to perform in situations—an incoming missile, a sinking ship—that could cause people to become paralyzed by fear. I’d learned in boxing and in my work overseas that human beings can inoculate themselves against uncontrolled fear. When I first stepped into a boxing ring to spar, my heart rate was high, my adrenaline pumped, my muscles were tense—and I got beat up. After years of Earl’s training I could get in a ring with an appreciation of how dangerous my opponent was, and I could keep my heart rate steady, my muscles

...more

The classmate I was running beside was an accomplished triathlete, and we looked at each other in disbelief at the panic around us. As we reached the half-mile mark, the sprinters had slowed desperately, and some were already at a jog. They were jogging, then sprinting, then coughing and stopping, then running again. We still had three and a half miles to go, and already these guys were in trouble. These were athletes: high school and college football players, water polo players, state champion wrestlers. Many of them would later ace the runs, but as we’d learn over and over again in BUD/S,

...more

The helo slowed to ten knots. We flew ten feet above the water of the bay, and the rotors whumped and churned the water into a wild froth. I was in charge of a boat crew of seven men and we all stood and formed a line. When the instructor pointed out the door, the first man jumped. The helo continued to fly, and we jumped at intervals one after another, inserting a long string of swimmers in the water. Hall was the second-to-last man to jump.

I learned how difficult it can be to stay focused when you’re worried about someone that you love, and for that learning I’m grateful. I think that it made me a better officer on deployment. I’d check in with guys: “You call home recently? Everything good?” Usually guys would just brag about how great their kids were doing. But on a few occasions, I had guys wake me up in the middle of the night to tell me that they feared their marriage was falling apart, or to tell me that their kid was sick. Strong guys would break down crying. Of course, just like life doesn’t stop at home, the mission

...more

At Officer Candidate School, our drill instructor used to say, “Lead from the front or get the hell out of the way.” That message echoed here. I don’t think that I realized it at the time, but one of the reasons the military can sometimes produce exceptional leaders is that military training clearly emphasizes the most important leadership quality of all: setting the example. Sometimes that example is physical: “You better be at the front of the run.” More often, and more importantly, the example is set by the actions you take that express your values. So, for example, SEAL officers eat last,

...more

What Warrant Green didn’t tell me, but what I came to learn, was that when you are leading, it can in fact be easier. For fear to take hold of you, it needs to be given room to run in your mind. As a leader, all the room in your mind is taken up by a focus on your men.

Some men had quit after the opening session on the grinder. Others quit after the run down the beach, and others quit after they sent us into the water. The men who quit then—I believe—were trapped in a cage of fear in their own minds. We woke to the sound of blanks being fired through machine guns. We got wet. We did pushups and flutter kicks. Instructors yelled at us. We ran on the beach. Every man in the class had endured at least this much before, so it could not have been the physical pain that made them quit. No. They lost focus on what they had to do in the moment, and their fear of

...more

This was not really “physical training” at all; it was spiritual training by physical means.

Each man quits for his own reasons, and it might be foolish to even attempt any general explanation. But if men were willing to train for months before ever joining the Navy, and then they were willing to enlist in the United States Navy and spend months in a boot camp and months in specialized training before they came to BUD/S, and if they were willing to subject themselves to the test of BUD/S and endure all of the pain and cold and trial that they had already endured up to this point, then it seems reasonable to ask, why did they quit now? They quit, I believe, because they allowed their

...more

Others simply didn’t let fear come to rest in their minds. They’d learned to recognize the feelings and they’d think, Welcome back, fear. Sorry I don’t have time to spend with you right now, and they’d concentrate on the job of helping their teammates.

SEALs are frequently misunderstood as America’s deadliest commando force. It’s true that SEALs are capable of great violence, but that’s not what makes SEALs truly special. Given two weeks of training and a bunch of rifles, any reasonably fit group of sixteen athletes (the size of a SEAL platoon) can be trained to do harm. What makes SEALs special is that we can be thoughtful, disciplined, and proportional in our use of force. Years later, in Iraq, I’d see a group of Rangers blow through a door behind which they believed there was an al Qaeda terrorist, take aim at the terrorist, assess that

...more

Warriors are warriors not because of their strength, but because of their ability to apply strength to good purpose.

And this was one of the great lessons of Hell Week. We learned that after almost eighty hours of constant physical pain and cold and torture and almost no sleep, when we felt that we could barely even stand, when we thought that we lacked even the strength to bend over and tie our boots, we could in fact pick up a forty-pound rucksack and run with it through the night.

People always ask me, “What kind of people make it through Hell Week?” The most basic answer is, “I don’t know.” I know—generally—who won’t make it through Hell Week. There are a dozen types that fail. The weightlifting meatheads who think that the size of their biceps is an indication of their strength; they usually fail. The kids covered in tattoos announcing to the world how tough they are; they usually fail. The preening leaders who don’t want to be dirty; they usually fail. The me-first, look-at-me, I’m-the-best former athletes who have always been told that they are stars and think that

...more

You emerge with swollen hands and swollen feet and cuts and bangs and bruises. You emerge weak and beaten. But the week does not transform you. While Hell Week emphasizes teamwork and caring for your men, it does not necessarily produce good people. Some of the best men I’ve known in the world are SEALs, but there are also some jerks, abusive boyfriends and husbands, men who fail to care, fail to lead, men with a few moral screws loose, who also make it through Hell Week. Hell Week tests the soul, it doesn’t clean it.

I went to Kabul with the headquarters element of the team, and after a few days of work there I left for a firebase. The firebase compound was surrounded by high mud walls. There was a dirt field inside the compound—just about the size of a baseball infield—and parked there were a dozen Humvees and Hilux trucks. Inside the firebase headquarters, beat-up desks were loaded with computers and the glow of the monitors lit the faces of the men who stood up periodically to move pins on a map to indicate where American teams were moving on the battlefield. Atop the highest wall of the compound,

...more

I love American idealism. I love the hopeful spirit of Americans endeavoring to shape the world for the better. A lot of times, though, many Americans—especially those in senior positions in government and the military—who have never spent a day working with people who suffer, can be blinded by the bright shining light of their own hopes. You cruise through a town where you don’t speak the language and offer someone a conversation about freedom or fifty bucks, most people will take the cash, thank you very much.

Treating Afghanis well was not only essential to the conduct of the campaign to win the intelligence war. I also began to see that it was essential for ourselves. The Taliban were often well trained, arguably often better trained to fight in Afghanistan than many American troops. So what makes us different from the Taliban? What distinguishes a warrior from a thug? Certainly it’s not the quality of our weapons or the length of our training. Ultimately we’re distinguished by our values. It would have been easy to abuse a prisoner, but any act of wanton personal brutality is not only

...more

Later, back in San Diego, people would ask me if it was hard to do this: was it hard to investigate my own men, hard to take statements about the conduct of fellow SEALs? I said then, and feel now, that whether or not it was hard was not relevant. It was necessary. No matter how many people we might upset, no matter how many supposed friends we might lose, our duty was to protect our men, the men who were doing the right thing. We couldn’t have men using drugs and firing live ammunition, using drugs and executing complex operations, using drugs and representing the United States. We couldn’t

...more