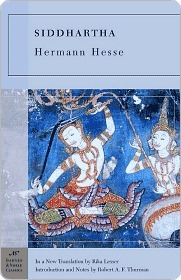

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Its simple prose and rebellious character echoed the yearnings of a generation that was seeking a way out of conformity, materialism and outward power.

this unrest, this intrinsic necessity of youth to unravel its path, the necessity we all have to claim what is truly and rightfully ours: our own life.

I thought of the supposedly crazy people inside who had revealed to me that they had decided to be locked away from the world because it was too difficult for them to deal with it. And I thought of Siddhartha, who had managed, by plunging into the very core of life, to find his way. I took a deep breath that morning, a breath that sought all the scents the world could contain and I made a promise: that I would choose life. Paulo Coelho

Shadows passed across his eyes in the mango grove during play, while his mother sang, during his father’s teachings, when with the learned men. Siddhartha had already long taken part in the learned men’s conversations, had engaged in debate with Govinda and had practised the art of contemplation and meditation with him.

Already he knew how to recognize Atman within the depth of his being, indestructible, at one with the universe.

There was happiness in his father’s heart because of his son who was intelligent and thirsty for knowledge; he saw him growing up to be a great learned man, a priest, a prince among Brahmins.

He loved Siddhartha’s eyes and clear voice. He loved the way he walked, his complete grace of movement; he loved everything that Siddhartha did and said, and above all he loved his intellect, his fine ardent thoughts, his strong will, his high vocation. Govinda knew that he would not become an ordinary Brahmin, a lazy sacrificial official, an avaricious dealer in magic sayings, a conceited worthless orator, a wicked sly priest, or just a good stupid sheep amongst a large herd. No, and he, Govinda, did not want to become any of these, not a Brahmin like ten thousand others of their kind.

That was how everybody loved Siddhartha. He delighted and made everybody happy. But Siddhartha himself was not happy. Wandering along the rosy paths of the fig garden, sitting in contemplation in the bluish shade of the grove, washing his limbs in the daily bath of atonement, offering sacrifices in the depths of the shady mango wood with complete grace of manner, beloved by all, a joy to all, there was yet no joy in his own heart. Dreams and restless thoughts came flowing to him from the river, from the twinkling stars at night, from the sun’s melting rays.

Siddhartha had begun to feel the seeds of discontent within him. He had begun to feel that the love of his father and mother, and also the love of his friend Govinda, would not always make him happy, give him peace, satisfy and suffice him. He had begun to suspect that his worthy father and his other teachers, the wise Brahmins, had already passed on to him the bulk and best of their wisdom, that they had already poured the sum total of their knowledge into his waiting vessel; and the vessel was not full, his intellect was not satisfied, his soul was not at peace, his heart was not still. The

...more

And what about the gods? Was it really Prajapati who had created the world? Was it not Atman, He alone, who had created it? Were not the gods forms created like me and you, mortal, transient? Was it therefore good and right, was it a sensible and worthy act to offer sacrifices to the gods? To whom else should one offer sacrifices, to whom else should one pay honour, but to Him, Atman, the Only One? And where was Atman to be found, where did He dwell, where did His eternal heart beat, if not within the Self, in the innermost, in the eternal which each person carried within him? But where was

...more

this tremendous amount of knowledge, collected and preserved by successive generations of wise Brahmins, could not be easily overlooked. But where were the Brahmins, the priests, the wise men, who were successful not only in having this most profound knowledge, but in experiencing it? Where were the initiated who, attaining Atman in sleep, could retain it in consciousness, in life, everywhere, in speech and in action?

his father — holy, learned, of highest esteem. His father was worthy of admiration; his manner was quiet and noble. He lived a good life, his words were wise; fine and noble thoughts dwelt in his head — but even he who knew so much, did he live in bliss, was he at peace? Was he not also a seeker, insatiable? Did he not go continually to the holy springs with an insatiable thirst, to the sacrifices, to books, to the Brahmins’ discourses? Why must he, the blameless one, wash away his sins and endeavour to cleanse himself anew each day? Was Atman then not within him? Was not then the source

...more

Around them hovered an atmosphere of still passion, of devastating service, of unpitying self-denial.

The flesh disappeared from his legs and cheeks. Strange dreams were reflected in his enlarged eyes. The nails grew long on his thin fingers and a dry, bristly beard appeared on his chin. His glance became icy when he encountered women; his lips curled with contempt when he passed through a town of well-dressed people. He saw businessmen trading, princes going to the hunt, mourners weeping over their dead, prostitutes offering themselves, doctors attending the sick, priests deciding the day for sowing, lovers making love, mothers soothing their children — and all were not worth a passing

...more

Siddhartha had one single goal — to become empty, to become empty of thirst, desire, dreams, pleasure and sorrow — to let the Self die. No longer to be Self, to experience the peace of an emptied heart, to experience pure thought — that was his goal. When all the Self was conquered and dead, when all passions and desires were silent, then the last must awaken, the innermost of Being that is no longer Self — the great secret!

‘What is meditation? What is abandonment of the body? What is fasting? What is the holding of breath? It is a flight from the Self, it is a temporary escape from the torment of Self. It is a temporary palliative against the pain and folly of life. The driver of oxen makes this same flight, takes this temporary drug when he drinks a few bowls of rice wine or coconut milk in the inn. He then no longer feels his Self, no longer feels the pain of life; he then experiences temporary escape. Falling asleep over his bowl of rice wine, he finds what Siddhartha and Govinda find when they escape from

...more

The Buddha went quietly on his way, lost in thought. His peaceful countenance was neither happy nor sad. He seemed to be smiling gently inwardly. With a secret smile, not unlike that of a healthy child, he walked along peacefully, quietly. He wore his gown and walked along exactly like the other monks, but his face and his step, his peaceful downward glance, his peaceful downward-hanging hand, and every finger of his hand spoke of peace, spoke of completeness, sought nothing, imitated nothing, reflected a continual quiet, an unfading light, an invulnerable peace.