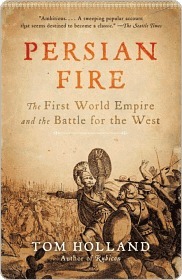

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Tom Holland

Started reading

July 29, 2022

Who precisely God might be, however, whether the Ahura Mazda of his ancestors’ pantheon, or the one supreme being proclaimed by Zoroaster, the new king was content to leave unclear. Ambiguity had its uses.

Bisitun,

Here, near the scene of his ambushing of Bardiya, Darius could offer sacrifice just as the Persians and the Medes had always done, in the sanctity of the pure and open air.

Yet the murder itself, the stern and epic quality of its execution, and the configuration of the assassins, would have conjured up associations for the followers of Zoroaster just as ripe with potential for Darius’ propaganda.

Six, according to the teachings of the Prophet, were the Amesha Spentas, the Beneficent Immortals who proceeded from Ahura Mazda – and six were the accomplices of Darius in his war against the Lie. That men might ponder this coincidence – ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

This seamless identification of his own power with that of a universal god was a development full of moment for the future.

Usurpers had been claiming divine sanction for their actions since time immemorial, but never such as Ahura Mazda could provide. Already, with the daring and creativity that were the trademarks of his style, Darius was moving with deadly speed to take advantage of this fact.

Dizzying as this startling ambition was, however, so too was the yawning of a waiting abyss.

The chosen one of Ahura Mazda could not afford to stumble: just one slip, and Darius would have failed. Already, as he and the other conspirators nursed their strength in Media, disturbing news was coming through to them of the empire’s reaction to their coup.

In Elam, an ancient kingdom on the borders of Persia, open revolt had broken out. In Babylon,* the great metropolis which was the largest and wealthiest city in the world, a pretender was repor...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Without dirt, there could never have been cities or great kings. So claimed the people of Babylon, who knew full well that their civilisation had been fashioned out of mud.

Lord Marduk, king of the gods,

the Esagila,

As Jeremiah, in far-off Judah, had wailed, ‘Their quiver is like an open tomb, they are all mighty men. They shall eat up your harvest and your food; they shall eat up your sons and your daughters; they shall eat up your flocks and your herds; they shall eat up your vines and your fig trees; your fortified cities in which you trust they shall destroy with the sword.’3 And all had come to pass just as the prophet had foreseen. In 586 BC, Jerusalem had been taken and left a blackened pile of rubble, and the hapless Judaeans hauled off into exile.

last king, Nabonidus,

Nebuchadnezzar III.

Here, for all those who had suffered from the Babylonians’ attentions in the past, was a name of ominous portent: for the second Nebuchadnezzar had been Babylon’s greatest ruler, the conqueror of Jerusalem and much more besides, a shatterer of cities and a breaker of proud nations, his memory preserved among those he had defeated as something fabulous, golden and deadly. But if the name of the new king would have sent shivers throughout the Near East, its effect on the Babylonians themselves would surely have been to set them dreaming.

Nebuchadnezzar II,

Here, millennia before Nebuchadnezzar, an intoxicating dream had

come to a man named Sargon, one never since forgotten, so that the kings of Babylon had been honoured to name themselves the kings of Akkad. Such a title, in contrast to some other Mesopotamian appellations – ‘King of the Four Quarters of the Earth’, say, or ‘King of the Universe’ – might have appeared modest; but it had served to link the kings of Babylon to the origins of empire.

Sargon, the obscure adventurer who had emerged as though from nowhere to nurture this proud ambition, to extinguish the independence of neighbouring city-states and to rule supreme over the ‘totality of the lands under heaven’,4 had always remained the model of a Mesopotamian strongman.

Almost two thousand years after his foundation of Akkad, he remained the cynosure of great kings. Indeed, in the decades before the Persian conquest, the obsession with him had become a veritable craze.

Sar...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Nabonidus

Nabonidus’ daughter, Princess En-nigaldi-Nanna,

Confronted by this menacing venerability, the Persians might have been expected to respond to it very differently: with suspicion, and even fear. It was not just that their own history, by comparison, was the merest blink of an eye.

And yet Cyrus, back in 539 BC, when he had first arrived in the city as its conqueror, had not been remotely intimidated. Indeed, he had shown himself far more sensitive to the alien and complex traditions of Mesopotamia, and to the potential they might offer his regime, than Nabonidus had ever done.

The last king of Babylon, fascinated though he was by antiquity, had eventually pushed his researches too far. Not content with hero-worshipping Sargon, he had also extolled the kings of Assyria, naming them his ‘royal ancestors’5 and adopting their ancient titles. This, in a city which one Assyrian king had sought to obliterate from the face of the earth, had been tactless, to say the least.

For a god more prickly with regard to his dignity it would have been hard to imagine. No mortal, not even the greatest monarch, could afford to offend him. This was why, every new year, the king was expected to visit the Esagila, the city’s greatest temple, to have his cheeks slapped and his ears yanked in a grand ritual of humiliation before the admonitory gaze of Marduk’s golden statue.

Nabonidus’ behaviour, to the Babylonians’ way of thinking, had been particularly egregious. Not only had he absented himself from Babylon, and therefore the Esagila, for ten whole years, but he had rubbed salt in the wounds by promoting the cult of a venerable moon god, Sin, in Marduk’s place.

By sponsoring the worship of Sin, Nabonidus had hoped to provide for his far-flung empire a less obviously chauvinistic focus of loyalty than the domineering Marduk. By doing so, however, he had laid himself fatally open to Cyrus’ propaganda.

Marduk’s

Nabonidus

Cambyses

The Egibis, for instance, a dynasty of bankers

Nabonidus

Egibis

Already, by early December, Persian outriders had reached the Median Wall. Next, turning its flank, Darius led his army over the Tigris, his soldiers clinging to horses, camels and inflated animal-skins. On 13 December 522 BC he met the army of Nebuchadnezzar III in battle, and routed it. Six days later, with a second victory, Darius completed his annihilation of the Babylonian forces.

Euphrates

Ishtar, the goddess of love,

Well might Babylon, to the Judaean exiles, have appeared a stew of licentiousness, and to those in distant countries, it was a superhuman and magical place.

In its streets, so it was whispered, prostitution was regarded as a sacred duty, and daughters would be joyously pimped by their own fathers. Not so much a city, Babylon was rather a veritable world unto itself. Indeed, ‘such was the immensity of her scale that Cyrus,’ it was claimed, ‘had been able to seize control of the outskirts without anyone in the centre even being aware of his arrival, so that the Babylonians, who were celebrating a festival, had continued dancing, and indulging themselves. And so it was that the city had fallen for the first time.’

The city, impregnable though it might have appeared, was in truth far too riven by division to be defended. If it was, as those who marvelled at it claimed, a mirror of the world, then the reflection that it offered was one of social and ethnic hatred. It was not only priests and businessmen who were eager to collaborate with the Persian king. Babylon was also filled with the descendants

of deportees, scattered throughout the suburbs. Few of these were willing to die in the cause of a Nebuchadnezzar. The cosmopolitanism of the great city, once the mark and buttress of its imperial might, now threatened it with anarchy. The Babylonians were bound to shrink from such a prospect, even at the cost of surrender to an alien master.

Chaos, in Mesopotamia, had always been the ultimate nightmare. Men knew that in the beginning all the world had been under the sway of demons, uncontrollable and savage, until the gods, taking pity on mankind, had established order by giving them a king. Without a monarch,...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

brilliant glazed blue of the main gateway,

Etemenanki, or ‘House that is the Frontier between the Heavens and the Earth’.

Beside the city’s main gates, open to the gaze of all who entered Babylon, there stood an immense palace, as visible, in its own way, as the Etemenanki at the opposite end of the boulevard; and yet such was the polychrome gorgeousness of its brickwork, inlaid as it was with gold and silver, and lapis lazuli, and ivory, and cedar, that those who viewed it could hardly help but lower their eyes to the ground. Opulence of such an order was not merely an expression of royal power, but was calculated, very precisely, to reinforce it. All were to feel submission and prostration in their souls.

Processional Way,

King of Persia,