More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

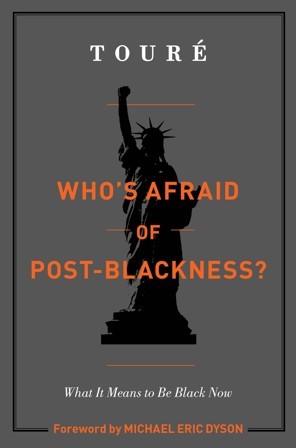

Touré

Read between

January 15 - January 16, 2012

He’s rooted in, but not restricted by, his Blackness.’”

The sheer plasticity of Blackness, the way it conforms to such a bewildering array of identities and struggles, and defeats the attempt to bind its meanings to any one camp or creature, makes a lot of Black folk nervous and defensive.

the very malleability of Blackness permits Black folk to shape it into weapons to fight on all sides of the debate about what Blackness is or isn’t.

Post-Blackness has little patience for racial patriotism, racial fundamentalism and racial policing.

Some Blacks may see the range of Black identity as something obvious but I know there are many who are unforgiving and intolerant of Black heterogeneity and still believe in concepts like “authentic” or “legitimate” Blackness.

“Sometimes Blackness is threatened,” says Kehinde Wiley, the visual artist, “by a desire to go outside of a collective sense of deprivation and to engage education and opportunity. It feels good to all be down with one another. This notion of being authentically Black is comforting. To be down is to be with it, to be with your people, to be part of the collective. But I think it’s time to grow out of that.

I was born in 1971 and as a child in the seventies I got that same sense—that being Black meant being born into an army that you had to somehow contribute to. Not necessarily in an armed or violent way, just as not everyone in the army goes into combat. “At

Post-Black means we are like Obama: rooted in but not restricted by Blackness. It means we love Blackness but accept the fact that we do not all view or perform the culture the same way given the vast variety of realities of modern Blackness.

Golden, along with the artist Glenn Ligon, coined the term “post-Blackness” as a way of describing something they saw happening in

art.

The fight for equality is not over but that shift from living amid segregation and civil war to integration and affirmative action and multiculturalism—and also glass ceilings, racial profiling, stereotype threat, microaggression, redlining, predatory lending, and other forms of modern racism—has led many to a very different perspective on Blackness than the previous generations had.

There’s this mandate that we have to feel this kind of trauma and then carry that with us through our lives.

It was very Black. I mean, Coretta Scott King was at one of these openings, you know, not talking to people, and you sang the Black national anthem and we looked at the artworks submitted by mostly amateurish artists, but there was a kind of a feeling of, you know, the kind of racial pride that felt to me a little passé maybe. Like, for me, I think it was that I was just so ambivalent about learning how to be devout about Blackness. I just had like this churning sense of anxiety and ambivalence and disappointment and a kind of individualism.”

There’s understanding about this work that would not have existed for the mainstream prior to now because there’s a certain amount of African-American history being used as the lingua franca for the country at this point.

Black culture was once coded and culturally distant, like the secluded juke joint off the beaten path where Blacks rollicked and explored their artistic and aesthetic souls and intrepid whites trekked out to it as if into the uncharted forest, to see something exotic. Now Black culture is more like Starbucks: located on every corner in every major city and available to anyone who wants in.

We have to get past this notion that Black culture is separate and apart from America, that it’s this object that can be studied but is so alien and foreign that only Black people can understand it and white people have no relationship to it. We have to move beyond these clear binaries about where culture is imagined to reside and who has ownership of it.”

Post-Black art presents Blackness not as an assault weapon—there’s more to Blackness than bludgeoning people with memories of past atrocities and injustices or the discussion of how difficult it is to be Black and deal with whites. Blackness is also something to investigate, enjoy, and ponder on its own terms.

Multi-culturalism destroyed the idea that certain cultural legacies belong to certain cultural groups and art in the post-Black era takes that freedom to the nth degree.

The post-Black era is filled with these sorts of cross-cultural mashups—from The Grey Album where Jay-Z’s vocals are mixed with Beatles music; to white singer-songwriter Nina Gordon’s cover of N.W.A.’s “Straight Outta Compton,” slowly singing their vulgar autobiographical rhymes over sweet acoustic guitar to Chappelle’s “Clayton Bigsby” sketch where a blind Black man believes himself a Klansman,

Wiley makes portraits of modern Black men drenched in hiphop tropes—the prominently branded clothing, the hi-tech accessories, the powerful poses—positioned to replicate specific paintings from the Renaissance as if to make it a form of visual sampling. If he were a music producer he’d give you hardcore New York MCs rhyming over Beethoven.

“Only in the hiphop generation,” he said, “could a Black guy call a white guy nigger and the white guy’s heart soar.”

My parents told us whites expected us to be late, slovenly, and subpar. We were to be articulate, smart, and never, ever play the fool.

You see yourself as the world sees you. This is why the constant bombardment of microaggressions can be so pernicious: They bring society’s inferior view of Blacks to our face and can chisel away at our self-esteem.

I think what had been programmed into me by my parents was achievement in America meant assimilation into whiteness. So there we were, this beautiful, well-mannered, middle-class Black family amongst all these whites and to be called niggers in that environment—it didn’t matter how we dressed, it didn’t matter what job my dad had or how big our house was. We were just niggers.

“The platinum-level authentic Negro,” Martin said, “is you grew up in public housing, crime, drugs, poverty. The gold level is you grew up in a middle-class Black neighborhood and you went to public schools and maybe to a Black college so you got a pretty good Black experience. Silver is you lived in a neighborhood that was really diverse where you had a mix of educated African-Americans and whites and you may have gone to a Black church but it wasn’t a Black Baptist church, it probably was Episcopalian or something on those lines. You might be in Jack and Jill, a whole different kind of Black

...more

The accusation of not being Black enough is impactful and damaging and can spark an epiphany, sending people plunging into themselves to question who they are and what they value and often lead them to change.

But if you look at the world now, if anything it’s becoming post-whiteness. Like whiteness is becoming less relevant as a marker of power, authority, civilization.