More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

What’s done is done though, and even now in my eighties, as I lie here in the old folks home, my room full of the smell of my own decaying body, awaiting a meal of whatever, mashed and diced and tasteless, a tube in my shank, the television tuned to some talk show peopled by idiots, I’ve got the memories of then, nearly seventy years ago, and they are as fresh as the moment.

The wind had blown away most of North and West Texas, along with Oklahoma, but the eastern part of Texas was lush with greenery and the soil was rich and there was enough rain so that things grew quick and hardy.

We had a leak in the roof, no electricity, a smoky wood stove, a rickety barn, a sleeping porch with a patched screen, and an outhouse prone to snakes.

Another thing different then was you learned about things like dying when you were quite young. It couldn’t be helped.

When I looked I saw a gray mess hung up in brambles.

That was when we heard the noise down below and saw the thing.

Mr. Ethan Nation was a big man in overalls with tufts of hair in his ears and crawling out of his nose. His boys were redheaded, jug-eared versions of him.

I once heard him say to Cecil, when he thought I was out of earshot, that if you took the Nation family’s brains and wadded them up together and stuck them up a gnat’s butt and shook the gnat, it’d sound like a ball bearing in a boxcar.

If East Texas was last on the list to get the things everyone else already had, then the colored of East Texas got whatever it was long after the whites, and then usually an inferior version. Lincoln may have long freed the slaves, but the colored of that time were not far off living as they had lived before the Civil War.

As we got out of the car the dog moved its tail a few times, then stopped, lest it wear itself out with enthusiasm.

As it turned out, the woman in the tree, her legs pulled up behind her and bound, her arms pulled across her chest, her hands over her shoulders, wrists tied to her ankles by rope, was named Janice Jane Willman.

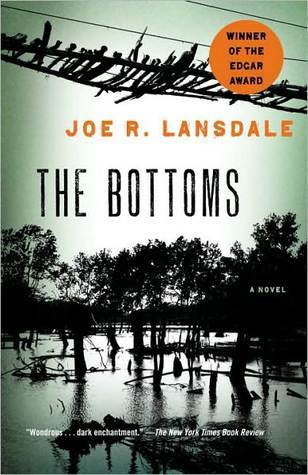

What was once the bottoms is hot sunlight on cement and no mystery. Seasons are not as defined. One month, save for the temperature or the weather, is not too unlike the next. Back then it was different. And that time of year, fall, was my favorite. Warm days, cool nights. Dark woods and a churning river. Leaves of many colors. The moon bright and gold.

I realized then every man in the room was watching her, like birds protecting a nest.

“And the only difference for colored now is the masters can’t sell ’em. Mose just missed being a slave, but he ain’t never had nothing but white folks on his butt.

Bill lived with his wife and two daughters, who looked as if they had fallen out of an ugly tree, hit every branch on the way down, then smacked the dirt solid.

People do foolish things, Harry. Things they wish they hadn’t done, but you can’t take them back. You have to live with them, get over them or work around them.”

I’m not sure a person ought to live to be too old. For when you can’t live life, you’re just burning life, sucking air and making turds.

Perhaps it’s not age, but health that matters. Live long and healthy, it doesn’t matter. But live long and unhealthy, it’s a living hell. And here I lie. Not doing well at all.

There’s no way to explain how bad it hurts to hear your father cry.

But like the poison ivy, looks could be deceptive. Under all the beauty, the bottoms held dark things, and I tell you true, I felt greatly relieved when we reached the Preacher’s Road.

Only our memories allow that some people ever existed. That they mattered, or mattered too much.

In the detective magazines the cops and private eyes saw a clue or two, they put it together. Cracked the whole case wide open. In real life, there were clues a plenty, but instead of cracking the case open, they just made it all the more confusing.

When we looked around for sign of the Goat Man, all we could find were prints from someone wearing large-sized shoes. No hoofprints.