More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

“What sort of spell?” All three looked at her as though she had asked what color a carrot is. “We’re witches,” said Hello. Manythanks pointed meaningfully at his hat. “But witches do all kinds of spells—” “That’s sorceresses,” corrected Goodbye. “And magic—” “That’s wizards,” sighed Hello. “And they change people into things—” “That’s thaumaturgists,” huffed Manythanks. “And make people do things—” “Enchantresses,” sneered Goodbye. “And they do curses and hexes—” “Stregas,” hissed both sisters. “And change into owls and cats—” “Brujas,” growled Manythanks. “Well … what do witches do, then?”

...more

“Hello, I believe we have an utterly unique specimen on our hands: a child who listens,” Goodbye said, laughing. Goodbye laughed a lot.

You see, the future is a kind of stew, a soup, a vichyssoise of the present and the past. That’s how you get the future: You mix up everything you did today with everything you did yesterday and all the days before and everything anyone you ever met did and anyone they ever met, too.

Goodbye hurried on. “But if some intrepid, brave, darling child went to the City and got it back for me, well, a witch would be grateful. You’ll know it right away: It’s a big wooden spoon, streaked with marrow and wine and sugar and yogurt and yesterday and grief and passion and jealousy and tomorrow. I’m sure the Marquess won’t miss it. She has so many nice things. And when you come back, we’ll make you a little black bustle and a black hat and teach you to call down the moon gulls and dance with the Giant Snails that guard the Pantry of Time.”

The trouble was, September didn’t know what sort of story she was in. Was it a merry one or a serious one? How ought she to act? If it were merry, she might dash after a Spoon, and it would all be a marvelous adventure, with funny rhymes and somersaults and a grand party with red lanterns at the end. But if it were a serious tale, she might have to do something important, something involving, with snow and arrows and enemies.

But no one may know the shape of the tale in which they move. And, perhaps, we do not truly know what sort of beast it is, either. Stories have a way of changing faces. They are unruly things, undisciplined, given to delinquency and the throwing of erasers. This is why we must close them up into thick, solid books, so they cannot get out and cause trouble.

There must be blood, the girl thought. There must always be blood. The Green Wind said that, so it must be true. It will all be hard and bloody, but there will be wonders, too, or else why bring me here at all? And it’s the wonders I’m after, even if I have to bleed for them.

am just a girl from Omaha. I can only do a few things. I can swim and read books and fix boilers if they are only a little broken. Sometimes, I can make very rash decisions when really I ought to keep quiet and be a good girl. If those are weapons you think might be useful, I will take them up and go after your Spoon.

distant owls call after mice. And then she suddenly remembered, like a crack of lightning in her mind, check your pockets. She laid her sceptre in the grass and dug into the pocket of her green smoking jacket. September pulled out a small crystal ball, glittering in the moonlight. A single perfectly green leaf hung suspended in it, swaying back and forth gently, as if blown by a faraway wind.

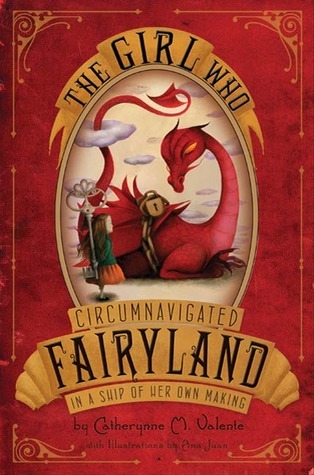

The beast’s lizardish skin glowed a profound red, the color of the very last embers of the fire. His horns (and these horns led September to presume the dragon a he) jutted out from his head like a young bull’s, fine and thick and black. He had his wings tucked neatly back along his knobbly spine—where they were bound with great bronze chains and fastened with an extremely serious-looking lock.

“First off, I am not a dragon. I don’t know where you could have gotten that idea. I was very careful to show you my feet. I am a Wyvern. No forepaws, see?”

“I am the Honorable Wyvern A-Through-L, small fey. I would say, ‘at your service,’ but that’s rather fussy, and I’m not, you see, so it would be inaccurate.”

‘Why do we not have a Papa?’ And she said, ‘Your Papa is the Library, and he loves you and will care for you. Do not expect a burly, handsome Wyvern to show up and show you how to breathe fire, my loves. None will come. But Compleat has books aplenty on the subject of combustion, and however odd it may seem, you are loved by two parents, just like any other beast.’”

“Why are your wings chained up?” she asked, eager to change the subject. A-Through-L looked at her as though she must be somehow addled. “It’s the law, you know. You can’t be so new as all that. Aeronautic locomotion is permitted only by means of Leopard or licensed Ragwort Stalk. I think you’ll agree I’m not a Leopard or made of Ragwort. I’m not allowed to fly.”

“The Marquess decreed that flight was an Unfair Advantage in matters of Love and Cross-Country Racing. But she’s awfully fond of cats, and no one can tell Ragwort to sit still, so she granted special dispensations.”

she’s the Marquess. She has a hat. And muscular magic, besides. No one says no to her. Do you say no to your queen?”

Home seemed very far away now, and she did not yet miss it. She knew, dimly, that this made her a bad daughter, but Fairyland was already so large and interesting that she tried not to think about that.

things are not all well in Fairyland, are they? The witches’ brothers are dead, and they’ve no Spoons, and your wings are all chained and sore—don’t say they aren’t, Ell. I can see where they’ve rubbed the skin away. And can I call you Ell? A-Through-L

What is the purpose of a Fairyland if everything lovely is outlawed, just like in the real world?”

September could not know that humans riding Marvelous Creatures of a Certain Size was also not allowed. A-Through-L knew, but for once he did not care.

Still, if a dragon—a Wyvern—brings it to me, September thought, it’s dragon food and not fairy food at all, and no one should blame me for breakfast.

When one is traveling, everything looks brighter and lovelier. That does not mean it is brighter and lovelier; it just means that sweet, kindly home suffers in comparison to tarted-up foreign places with all their jewels on.

September read often, and liked it best when words did not pretend to be simple, but put on their full armor and rode out with colors flying.

“As you might expect, the geographical location of the capital of Fairyland is fickle and has a rather short temper. I’m afraid the whole thing moves around according to the needs of narrative.”

“My name is Lye,” the soap-woman said. A few bubbles escaped her mouth. She was utterly still. No soapy muscle trembled. “It is my part to welcome you, to show you to the baths, to tend to you and to all weary travelers, until my mistress returns, which will not be long now, I’m sure.”

“I am a golem, child,” answered Lye calmly. “My mistress wrote it there.

One of the things she knew was how to gather up all the slips of soap the bath house patrons left behind and arrange them into a girl shape and write ‘truth’ on her forehead and wake her up and give her a name and say to her: ‘Be my friend and love me, for the world is terrible lonely and I am sad.’”

“She sounds like someone who spends a lot of time in libraries, which are the best sorts of people.”

I am still here, and I keep going, and I never stop because I don’t know how to stop because she said I’d never have to stop.”

slough off in the rain.” “Oh, darling Lye,” cried the Wyverary. “How I wish I could bring you good news! But late in the golden reign of the Queen, the Marquess arrived and destroyed her. Or made her sit in a corner. Reports vary. And now there are complicated proclamations, and the lamentations of the hills and my wings are locked down to my skin, and no one has cocoa at all.

“My mistress used to say that you couldn’t ever really be naked unless you wanted to be. She said, ‘Even if you’ve taken off every stitch of clothing, you still have your secrets, your history, your true name.

“This is the tub for washing your courage,

“When you are born,” the golem said softly, “your courage is new and clean. You are brave enough for anything: crawling off of staircases, saying your first words without fearing that someone will think you are foolish, putting strange things in your mouth. But as you get older, your courage attracts gunk and crusty things and dirt and fear and knowing how bad things can get and what pain feels like.

“For the wishes of one’s old life wither and shrivel like old leaves if they are not replaced with new wishes when the world changes. And the world always changes. Wishes get slimy, and their colors fade, and soon they are just mud, like all the rest of the mud, and not wishes at all, but regrets. The trouble is, not everyone can tell when they ought to launder their wishes. Even when one finds oneself in Fairyland and not at home at all, it is not always so easy to remember to catch the world in its changing and change with it.”

“Lastly,” Lye said, “we must wash your luck.

The House Without Warning was possessed of a small door nestled beside a marble statue of Pan blowing his horn—if only September

It was too late for warnings now, as the House well knew.

Now, jackals are not the wicked creatures some irresponsible folklorists would have children believe. They are quite sweet and soft, and their ears are clever and enormous. Such a lovely creature the little girl had become.

“Did you know,” said the Wyverary happily, snuffling the fresh air with his huge nostrils, “that the Barleybroom used to be full of tea? There was an undertow of tea leaves, flowing in from some tributary. It used to be, oh, the color of brandy, with little bits of lemon peel floating in it and lumps of sugar like lily pads.”

Perhaps it was Lye’s bath, but she felt quite bold and intrepid and, having paid her own way, quite grown-up. This inevitably leads to disastrous decisions, but September could not know that, not then when the sun was so very bright and the river so blue. Let us allow her these new, strange pleasures.

though you can have grief without adventures, you cannot have adventures without grief.

September did not answer. A shadow fell over her as she thought of how often she had heard older girls in her school bathrooms talk about how they would go one day to a place called Los Angeles and be stars,

She did not want to think that Pandemonium could be like that. She did not want Fairyland to be full of older girls who wanted to be stars.

Well, being frogs was no kind of fun, so we went about and stole better bits—wings from dragonflies and faces from people and hearts from birds and horns from various goats and antelope-ish things and souls from ifrits and tails from cows—and we evolved over a million million minutes, just like you.”

“It’s Survival of Them Who’s Best at Nicking Things, girl!”

As for why we’re not exactly thick on the ground, that’s none of yours, and I’ll thank you not to pry into family business.”

But she did not want to be a tithe, and she did not want to die, even a little bit, and she did not even want to brush shoulders with the smallest chance of

“You have a voice,” he said slowly, “and a shadow. Choose one, and I will take it instead of the skin-shrugger.” You might think that is no kind of choice. But September was suspicious. No bargain in Fairyland could be that easy.

The Glashtyn set the scrap of something down before him. It pooled darkly, shining a little, and then stood up in the shape of a girl just September’s height, with just September’s eyes and hair, all of black smoke and shadow. Slowly, the shadow-September smiled and pirouetted on one foot. It was not a gentle smile or a kind one.

“Did I do the right thing, Charlie?” September asked the ferryman softly. He shook his mad gray head. “Right or blight, done is dusted.”