More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

A far happier event during the production of Chained involved Joan and Clark. For all his efforts to separate them, Mayer now behaved with astonishing perversity, insisting that they be reunited romantically on-screen. In this picture, the two friends shared several unusually long dialogue scenes, set in a ship’s swimming pool and at lunch. The script they received for these sequences consisted of inconsequential remarks intended to be mere filler but disguised as exchanges—and after the two actors had seen their lines, they agreed to take matters into their own hands. When the scenes were

...more

her consorting with “people of culture and taste,” she never forgot—and was usually more comfortable with—the average, unknown, behind-the-scenes workers who crossed her path. Joan befriended film crews and technicians as she did executives, remembering their birthdays, asking about their families, paying hospital and doctor bills for the indigent and providing financial assistance to help families who were ill or had fallen on hard times—as so many did in the 1930s. These generous acts were done quietly, and anyone who publicized her generosity was soundly chastised. Some

These people were to receive all necessary care at the Hollywood Presbyterian Hospital, where she endowed several rooms and a surgical suite. All the bills were sent to her and she paid them quickly and privately, without referring them to her business manager. The arrangement was made on condition that her name not be used, and that she receive no credit or publicity for her charity in any way; years later, when this bequest was discovered and Joan was openly praised, she feigned ignorance of the entire matter. “In the two years after 1937, more than 390 major surgeries were completed,”

...more

Those last three words summarized perfectly the essence of Joan Crawford. “My insecurities made me carry things a little too far—for my ownpersonal comfort and the comfort of the people around me,” she said late in life. “I played the star Joan Crawford, not the woman Joan Crawford, to the hilt.” Ths is not hard to understand. She labored ceaselessly to eradicate every trace of Lucille

A light fell on top of him, also narrowly missing her. I was whisked away, and production, of course, was halted. The studio ambulance arrived and he was taken immediately to the hospital. Eventually, the scene resumed. I was impressed by Miss Crawford’s concern for the man, for his family, for the medical attention he received. She wanted absolute assurances that he was cared for properly, that he remained on salary, and that his family was provided for. She would not resume shooting until those assurances were given, and she called the hospital each day for reports on his condition. For all

...more

On the one hand, he played it safe: Mannequin returned Joan to her role as a poor working girl who becomes a rich wife (as in Possessed, Sadie McKee and Chained)—a formula that was always a surefire Depression-era crowd pleaser. This time, she left a shiftless, opportunistic husband (Alan Curtis) for a generous and adoring tycoon (Spencer Tracy), whom Mankiewicz deliberately cast because Tracy was less “movie-star handsome” than Curtis. But

Joan’s increasing obsession with cleanliness—her mania for an almost impossibly tidy and sanitary existence—was certainly a sign of her interior need to cleanse and purify, as much as it was a sign of her longing to unite her actual life with her ideal life, to join the reality of the kitchen to the art of her perfect movie-fake kitchen. The laundry assistant was a permanent part of her personality, and something in Joan prevented her from eradicating it. IN MAY 1938, THE Independent Film Journal, published by the Independent Theatre Owners

More to the point, Mayer at once concluded negotiations with Joan’s agent for a new contract—$330,000 annually over the next five years. “Box-office poison?” asked Joan rhetorically. “Mr. Mayer always asserted that the studio had built Stage 22, Stage 24 and the Irving Thalberg Building, brick by brick, from the income on my pictures.” That was no exaggeration. Indeed, the tight-fisted, cheese-paring Mayer regarded the financial failure of Joan’s recent films as but a temporary setback due

not to anything like a lack of talent on her part. Had they seen her as no longer profitable, Metro’s executives would not have eagerly acceded to her agent’s demands and quickly closed the deal that guaranteed her a record income for five years to come. The news

good: in The Women, she gladly accepted a minor role and performed it to mordant, wicked perfection. Nor did Joan balk at assuming a part in support of her old rival, Norma Shearer: “I’d play Wally Beery’s grandmother if it was a good part,” she said famously, and she meant it. In fact, she had to fight for the part, which Mayer thought too small and too unsympathetic; she landed

adversity. No director could have handled Strange Cargo with more understanding. THE PICTURE CONCERNS A motley group of Devil’s Island prisoners who escape and cut a path to freedom through the jungle and then by a perilous sea journey. Led by a tough rogue named Verne (Gable), the men are

by the cabaret performer and sometime hooker Julie (Joan) and by a mysterious, mystical figure named Cambreau (Ian Hunter). Strange Cargo is simultaneously a suspense yarn, a sea epic and a love story—but most of all it is a meditation on the nature of human solidarity, the possibility of forgiveness and thenature of redemption. This complex of ideas emerges in a film made with tact, restraint and unpretentious depth—a rare combination of qualities in Hollywood at any time. The impressive

Strange Cargo remains one of Joan’s most audacious and exceptional accomplishments. THE FILM WAS COMPLETED with

Perhaps it was no surprise that this work captured her interest: Strange Cargo had explicitly treated the theme of the indwelling divine presence in all people, and the Crothers play satirized shallow religious pretense in the person of a wealthy, scatterbrained woman who mistakes fad for faith. For many years, the tale has been

SUSAN AND GOD REFLECTS indirectly on the nature of an authentic religious conviction—that is, the play affirms faith as mystery and, primarily, a matter of goodwill to others. Rachel Crothers, one of the most important and respected of American playwrights, had seen twenty-eight

Joan’s acting was a triumph of improvisation, a virtuoso succession of mockeries, capricious gestures, witty intonations and credible dynamics: she understood

There were several reasons for this unusual state of affairs, but primary among them was Joan’s longing for children. Her friendship with Margaret Sullavan had revived that desire, hitherto frustrated by miscarriages and Fran-chot’s indifference to fatherhood (“I don’t think he especially wanted a child,” she said). She knew the legal obstacles were formidable, but

Because she “carried her own camera,” Joan documented many episodes during this love affair, and she kept the filmed record until her death. Several hours long and covering three years, the film was discovered many years later by her family and was first publicly shown on December 5, 2008, at a Joan Crawford festival at the University of California, Los Angeles. The color footage shows a woman happy and relaxed, enjoying her private life with her lover and (by 1942) two babies. Holding the camera, McCabe focused on Joan strolling in the woods, paddling a canoe, reclining on the grass and

...more

JOAN’S SILENCE ABOUT THE baby girl she wanted to adopt was broken when she first spoke publicly, on May 23, 1940, in a news release she carefully prepared. “Her transcontinental journeys were for the purpose of adopting a baby,” the Los Angeles Times reported. She did not reply when asked the name of the New York orphanage at which she claimed to have obtained Christina—the name on which she had settled for the baby girl. Although biographers have categorically insisted that Joan returned with the child to Los Angeles at onceand celebrated her first birthday there with a lavish party in June,

...more

baby jewelry. She was constantly holding me and looking at me … [and] whenever she didn’t take me to the studio, she would rush home in time to feed me and give me my bath. She would sing lullabies to me and rock me to sleep … My adoring, indulgent mother couldn’t resist giving me anything I asked from her. In return, she had my total devotion.” AFTER INTERVIEWING

The two actresses met at Selznick’s party for the premiere of Intermezzo, where Joan was able to turn the conversation to A Woman’s Face. She wanted to know if Ingrid would be offended if Joan were to ask Mayer (Selznick’s father-in-law) to secure the rights for Joan to appear in an American remake of the picture. She knew this might seem impertinent, but there were so few good roles for an actress. Ingrid laughed and dismissed the idea of “offense,” saying that, after all, they were there to celebrate a Hollywood remake of a Swedish film for her—so why not a Hollywood remake of a Swedish film

...more

Culver City. Another reason for Joan’s settling on A Woman’s Face was—her face. She was entering a period of mature, almost statuesque beauty, but she was also afraid of being considered too old to be cast as a leading lady. In 1941 she would turn thirty-five, and well-founded rumors were circulating that both Garbo (thirty-six) and Shearer (thirty-nine) intended to quit the business permanently—primarily over disputes about the quality of their assignments, but also because they knew that leading roles were scarce for “aging women” (which meant actresses past their midthirties). And so Joan

...more

picture. Metro, afraid that too many people would wrongly regard A Woman’s Face as a horror picture, released no photos or even hints of the character’s disfigurement. Cukor’s direction was, as usual, expert, and Robert Planck’s atmospheric cinematography consisted of shifting pools of key lights and arresting shadows.

“I have nothing but the best to say for A Woman’s Face,” she told an interviewer many years later. “It was a splendid script, and George [Cukor] let me run with it. I finally shocked both the critics and the public into realizing the fact that I really was at heart a dramatic actress. Great thanks to Melvyn Douglas [costarring with Joan for the third time]; I think he is one of the least appreciated actors the screen has ever used. His sense of underplay, subordination, whatever you call it, was always flawless. I say a prayer for Mr. Cukor every time I think of what A Woman’s Face did for my

...more

A Woman’s Face might well be regarded as the third picture in a trilogy of transformations. From the tested Julie of Strange Cargo to the chastened Susan in Susan and God and on through the transformation of Anna Holm, Joan drew on the crises in her own life to present three women. This was certainly not a conscious intention on her part—nor were the films planned as a trilogy—but an actress cannot leave herself at home when she steps onto a soundstage. It was this Joan Crawford

But in October, after months of news stories had appeared about Joan’s second adoption, Kullberg’s mother (as he wrote) “started to feel guilty about giving up her child and decided to pursue my return.” A single news release giving his exact birth date, followed by some basic private detective work, led the mother to her baby’s new residence. “She wrote letters to Alice Hough and Joan Crawford, demanding my return, threatening suit and negative publicity. I was returned to the Kullberg home in November of 1941.”

So it happened that, for five months, Joan had an infant son she had named Christopher Crawford, and then he was gone. “She adored you,” wrote Betty Barker, Joan’s secretary, years later, “and she was broken-hearted when she had to return you to your natural mother. I remember that she wanted to fight the case, but her lawyers convinced her that she couldn’t win. When she lost you, all of us were afraid to mention your name to her for years, as it was a tender subject with her. She would have loved to have known what happened to you.

All this succeeds as sparkling entertainment, thanks in no small part to the skill of Robert Z. Leonard, who had directed Dancing Lady and was working on his 135th picture. Very much an ensemble piece, When Ladies Meet remains a rare kind of grown-up comedy. It contains an enormous amount of common sense combined with smooth moviemaking craftsmanship, perfectly timed and subtle performances and a rare knowledge of and faith in human nature. Like Susan and God, the original Crothers play won coveted prizes; as a movie, When Ladies Meet retains a wise and mature humor that only the most cynical

...more

Nevertheless, she turned over her entire salary for the picture ($112,500) to the American Red Cross, which had braved the wintry elements to recover the remains of Carole and her mother. When she learned that her manager had withheld his 10 percent fee and sent on the balance to the Red Cross, she made up the sum and promptly dismissed him. JOAN’S RELATIONSHIP

spring. She had found herself too deeply attached to settle for the permanent role of the other woman in a real-life remake of Back Street, and when it was clear that they could never have a life together, she had to end the affair. Perhaps contrary to her expectations, she was at once unutterably depressed. She had lost the second adopted baby, and now McCabe’s departure left her feeling lonely and useless. In May,

and in November she went back to work on yet another movie set in war-torn Europe. This one turned out to be a remarkable and effective entertainment, however. Based on a novel by Helen Maclnnes, Above Suspicion successfully treated the horror of war and the futility of murderous espionage by satire and allusion. Director Richard Thorpe economically guided Joan, costars Fred MacMurray, Conrad Veidt, Basil Rathbone and a large and capable roster of European actors through the episodes of a literate and witty screenplay.

Above Suspicion certainly seems to be a kind of homage to Hitchcock. The absurd story is spun so deftly that there is time only to enjoy the polished performances and the breakneck pace of the comic action. Although she chafed more than ever under Metro’s incautious handling of her career, Joan nevertheless created a portrait of a spritely, loving and confident bride who becomes a resourceful spy. Although she claimed not to have enjoyed the production, this is never apparent. As in Chained, Love on the Run, Susan and God and When Ladies Meet, Joan’s talents extended beyond flaming-youth

...more

did all the housework: cooking, sewing, decorating, repainting and, with Phillip’s help, a fair amount of repairing and rebuilding. Most of all, she had her own intensive method of cleaning, which was a way of putting her seal on something, of exerting control, of making something turn out right. Her methods of housekeeping were excessive and needlessly repeated, but this was a benign compulsion. And so she scrubbed and cleaned and reorganized her closets, and then she cleaned some more, and applied fresh paint to the cupboards. “There were spells between cooking, cleaning, washing and sewing

...more

“But when I started to feel too depressed, I suddenly remembered what lousy stories they’d given me, and then I got good and mad and walked out without a tear. The people I hated leaving were my crews—the electricians, makeup people, hairdressers, wardrobe. They really seemed like family to me.” One worker who had been at Metro more than

With her colleagues, Joan was all business; and to some—like sixteen-year-old Ann Blyth—she was actually protective. Warner and Curtiz had not wanted Ann for the role, but Joan was adamant when she saw the girl’s test. Her confidence was justified, for the result was Ann’s chillingly effective portrayal of the spoiled, cruelly self-centered Veda. “The Joan Crawford I knew,” recalled Ann Blyth decades later, “was dedicated and kind. She fought for me to have the part of Veda, and she told the director when she thought I ought to have more close-ups. Nobody I ever worked with enjoyed being a

...more

Joan’s portrait of Mildred Pierce was a study in understatement, moderation, control and depth—the triumph of her old adage that in the movies, less is more. When Mildred strikes Veda, the sting is reflected in her own reaction. When

With this character and this movie, Joan Crawford commenced what might be called a third act in her motion picture career. From 1925 to 1938, she had represented successively the raging party girl, the sensual but irrepressible working woman, the benighted or isolated victim and the society matron. From 1939 to 1943, she brought a remarkable technical complexity to a wide variety of roles in no fewer than five first-rate films (Strange Cargo, Susan and God, A Woman’s Face, When Ladies Meet and Above Suspicion). But Mildred Pierce took her and audiences to a new level, in which she would

...more

obsessions. She was irresistible to an actress who wanted a substantial, unforgettable role—not merely one that would win the love of fans and critics. Humoresque began filming in late December 1945, and with her weekly salary still in place, Joan was able (after taxes and salaries to agents, managers, publicists and a new team of household employees) to bank about $40,000 that year. This was a princely income at a time when the average American salary was $3,150 annually, and when a substantial home could be purchased for $12,500.

Joan was enormously inventive in bringing Helen Wright to life, and she was canny in undertaking so unsympathetic a role. In this regard, it is fascinating to see how she managed her career in the postwar period, finding new roles and fresh depths in herself. Unconcerned about the amiability

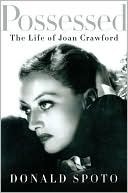

Considered retrospectively, Possessed was like the final installment of a Joan Crawford trilogy that had begun with her portrayals of neurotic Mildred and continued with destructive Helen. In this “heavy picture” (as she called it), Joan was the extreme character of the previous two: lovesick, psychotic Louise Howell, consumed by a lunatic obsession for a man who does not return her brand of possessive love. Here, characters formerly rendered by

Daisy Kenyon was produced that summer of 1947 and released at year’s end. Joan worked amiably with costars Dana Andrews and Henry Fonda, and she described director Otto Preminger as “the kindest, sweetest man"—not a typical sentiment about a man with the reputation of reducing actors to tears, nervous collapse and

feverish anxiety. None of those involved in the production of Daisy Kenyon retained a high regard for it—which is odd, for it not only offers one of Joan’s most forthright and warm performances, but also showcases her in a story of striking complexity and maturity, one of her most important and appealing pictures. Joan was fortunate to work with Andrews and Fonda, first-rate actors she specifically requested, both of them remarkable in this movie for giving deeply affecting performances. Very

There is a strange and enduring paradox about Mommie Dearest and its author—indeed, there seems to be a glaring logical flaw at its center. Christina Crawford asserted that her life was blighted by Joan’s cruelty. But from the age of ten—precisely when she claims the punitive disciplinary acts shifted into full gear—Christina was in fact having considerable success at several schools, where she enjoyed the admiration of her teachers and the friendship of her classmates. From her elementary years through her college education, she achieved high marks and was awarded diplomas and degrees with

...more

Virtually all other considerations of Joan’s life and career were minimized or dismissed. With the passing of years and the accumulated witness of other voices

than Christina’s, it became clear that Mommie Dearest offered at the least an overstated, skewed image of its subject. At its worst, it was a vituperative act of revenge after Joan excised her two oldest children from her will after many years of discord. “When Joan didn’t include [Christina] in her will,” according to Nolan Miller, one of Joan’s couturiers, “Christina wrote the book as a retaliation.” He was not alone in this opinion, which was shared by a legion of Joan’s friends—and by Joan’s adopted twins.4 The

incident, which inspired the movie’s most bizarre and infamous scene, actually reflected a time when Joan forbade hangers rather than a time when she nearly killed the child for using those hangers. (Christina never wrote that she was beaten with wire hangers, but rather that she was beaten because she had wire hangers in her closet.) But the truth of the matter is that the laundry company and the dry cleaners to which Joan entrusted the family’s clothes were under strict instructions to return all clothing on the richly covered hangers Joan provided. Could the company have failed once and

...more

THERE ARE ALSO ODD inconsistencies between the horrific discipline and what Christina described elsewhere. “Unexpected moments of real closeness between us always brought tears to her eyes,” Christina wrote about her relationship with Joan. And to a journalist, she said, “Mommie was with me constantly. No matter where she went. When she traveled across the country, I went

along too. And she read poetry to me in that marvelous voice of hers—the poems of Edna St. Vincent Millay and the sonnets of Shakespeare. When I learned to read, we took turns reciting stanzas. Mother loved poetry and she wanted me to be exposed to it as early as possible.” When she spoke of Joan’s preoccupation with her career, Christina was, on another occasion, quite understanding: “As I grew older, I saw less and less of Mommie. Not that she didn’t try to give us time. The problem was that she didn’t have that much [time to give]. You can’t build a career like she built and have a great

...more

“She was not a maternal person,” according to Dorothy Manners, who inherited the Louella Parsons column. “It was not her instinct. Adopting those children was the thing to do. Joan was a kind person, but her blind spot was her children.” It seems, then, that there was indeed strict discipline in the Crawford home—but that it was neither as brutal nor as physical as Mommie Dearest claims. (By the time Christina was nine, she and Joan fought almost constantly: “I was probably not too pleasant a child,” she admitted.) Joan never offered excuses for disciplining

Joan hated her past. But as often happens, she recreated its circumstances in order to reverse it once and for all. It is also worth nothing that, from this time in her life, she very rarely undertook a sympathetic movie role. Unhappy