More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

I consider that the spiritual life is the life of man’s real self, the life of that interior self whose flame is so often allowed to be smothered under the ashes of anxiety and futile concern. The spiritual life is oriented toward God, rather than toward the immediate satisfaction of the material needs of life, but it is not, for all that, a life of unreality or a life of dreams. On the contrary, without a life of the spirit, our whole existence becomes unsubstantial and illusory. The life of the spirit, by integrating us in the real order established by God, puts us in the fullest possible

...more

No matter how ruined man and his world may seem to be, and no matter how terrible man’s despair may become, as long as he continues to be a man his very humanity continues to tell him that life has a meaning.

First of all, although men have a common destiny, each individual also has to work out his own personal salvation for himself in fear and trembling.

Although in the end we alone are capable of experiencing who we are, we are instinctively gifted in watching how others experience themselves.

Now anxiety is the mark of spiritual insecurity. It is the fruit of unanswered questions. But questions cannot go unanswered unless they first be asked.

One of the moral diseases we communicate to one another in society comes from huddling together in the pale light of an insufficient answer to a question we are afraid to ask. But there are other diseases also. There is the laziness that pretends to dignify itself by the name of despair, and that teaches us to ignore both the question and the answer. And there is the despair which dresses itself up as science or philosophy and amuses itself with clever answers to clever questions—none of which have anything to do with the problems of life. Finally there is the worst and most insidious despair,

...more

What every man looks for in life is his own salvation and the salvation of the men he lives with. By salvation I mean first of all the full discovery of who he himself really is. Then I mean something of the fulfillment of his own God-given powers, in the love of others and of God. I mean also the discovery that he cannot find himself in himself alone, but that he must find himself in and through others.

The salvation I speak of is not merely a subjective, psychological thing—a self-realization in the order of nature. It is an objective and mystical reality—the finding of ourselves in Christ, in the Spirit, or, if you prefer, in the supernatural order. This includes and sublimates and perfects the natural self-realization which it to some extent presupposes, and usually effects, and always transcends.

Therefore this discovery of ourselves is always a losing of ourselves—a death and a resurrection.

To find “ourselves” then is to find not only our poor, limited, perplexed souls, but to find the power of God

This discovery of Christ is never genuine if it is nothing but a flight from ourselves. On the contrary, it cannot be an escape. It must be a fulfillment. I cannot discover God in myself and myself in Him unless I have the courage to face myself exactly as I am, with all my limitations, and to accept others as they are, with all their limitations. The religious answer is not religious if it is not fully real. Evasion is the answer of superstition.

I must learn to deprive myself of good things in order to give them to others who have a greater need of them than I. And so I must in a certain sense “hate” myself in order to love others.

Heroism in this sacrifice is measured precisely by madness: it is all the greater when it is offered for a more trivial motive.

The true answer, which is supernatural, tells us that we must love ourselves in order to be able to love others, that we must find ourselves by giving ourselves to them.

The difficulty of this commandment lies in the paradox that it would have us love ourselves unselfishly, because even our love of ourselves is something we owe to others.

What do I mean by loving ourselves properly? I mean, first of all, desiring to live, accepting life as a very great gift and a great good, not because of what it gives us, but because of what it enables us to give to others.

There is a dark force for destruction within us, which someone has called the “death instinct.” It is a terribly powerful thing, this force generated by our own frustrated self-love battling with itself. It is the power of a self-love that has turned into self-hatred and which, in adoring itself, adores the monster by which it is consumed.

It is therefore of supreme importance that we consent to live not for ourselves but for others. When we do this we will be able first of all to face and accept our own limitations.

Only when we see ourselves in our true human context, as members of a race which is intended to be one organism and “one body,” will we begin to understand the positive importance not only of the successes but of the failures and accidents in our lives.

My successes are not my own. The way to them was prepared by others. The fruit of my labors is not my own: for I am preparing the way for the achievements of another. Nor are my failures my own. They may spring from the failure of another, but they are also compensated for by another’s achievement. Therefore the meaning of my life is not to be looked for merely in the sum total of my own achievements. It is seen only in the complete integration of my achievements and failures with the achievements and failures of my own generation, and society, and time.

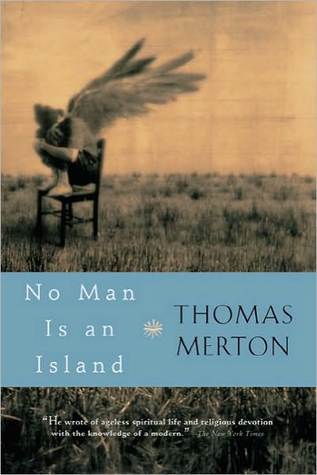

Nothing at all makes sense, unless we admit, with John Donne, that: “No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main.”

A happiness that is sought for ourselves alone can never be found: for a happiness that is diminished by being shared is not big enough to make us happy.

Infinite sharing is the law of God’s inner life. He has made the sharing of ourselves the law of our own being, so that it is in loving others that we best love ourselves.

Love seeks its whole good in the good of the beloved, and to divide that good would be to diminish love. Such a division would not only weaken the action of love, but in doing so would also diminish its joy. For love does not seek a joy that follows from its effect: its joy is in the effect itself, which is the good of the beloved. Consequently, if my love be pure I do not even have to seek for myself the satisfaction of loving. Love seeks one thing only: the good of the one loved. It leaves all the other secondary effects to take care of themselves. Love, therefore, is its own reward.

To love blindly is to love selfishly, because the goal of such love is not the real advantage of the beloved but only the exercise of love in our own souls. Such love cannot seem to be love unless it pretends to seek the good of the one loved.

Charity is neither weak nor blind. It is essentially prudent, just, temperate, and strong.

And since love is a matter of practical and concrete human relations, the truth we must love when we love our brothers is not mere abstract speculation: it is the moral truth that is to be embodied and given life in our own destiny and theirs.

The truth we must love in loving our brothers is the concrete destiny and sanctity that are willed for them by the love of God. One who really loves another is not merely moved by the desire to see him contented and healthy and prosperous in this world. Love cannot be satisfied with anything so incomplete. If I am to love my brother, I must somehow enter deep into the mystery of God’s love for him. I must be moved not only by human sympathy but by that divine sympathy which is revealed to us in Jesus and which enriches our own lives by the outpouring of the Holy Spirit in our hearts.

Charity makes me seek far more than the satisfaction of my own desires, even though they be aimed at another’s good. It must also make me an instrument of God’s Providence in their lives. I must become convinced and penetrated by the realization that without my love for them they may perhaps not achieve the things God has willed for them. My will must be the instrument of God’s will in helping them create their destiny. My love must be to them the “sacrament” of the mysterious and infinitely selfless love God has for them.

In order to love others with perfect charity I must be true to them, to myself, and to God.

For love must not only seek the truth in the lives of those around us; it must find it there. But when we find the truth that shapes our lives we have found more than an idea. We have found a Person.

To love myself more than others is to be untrue to myself as well as to them. The more I seek to take advantage of others the less of a person will I myself be, for the anxiety to possess what I should not have narrows and diminishes my own soul.

We are not perfectly free until we live in pure hope.

The only thing faith and hope do not give us is the clear vision of Him Whom we possess. We are united to Him in darkness, because we have to hope. Spes quae videtur non est spes.*

Nothing created is of any ultimate use without hope. To place your trust in visible things is to live in despair.

All things are at once good and imperfect. The goodness bears witness to the goodness of God. But the imperfection of all things reminds us to leave them in order to live in hope.

To be at enmity with life is to have nothing to live for.

But the pride of those who live as if they believed they were better than anyone else is rooted in a secret failure to believe in their own goodness. If I can see clear enough to realize that I am good because God has willed me to be good, I will at the same time be able to see more clearly the goodness of other men and of God.

Only the man who has had to face despair is really convinced that he needs mercy. Those who do not want mercy never seek it. It is better to find God on the threshold of despair than to risk our lives in a complacency that has never felt the need of forgiveness. A life that is without problems may literally be more hopeless than one that always verges on despair.

By hope all the truths that are presented to the whole world in an abstract and impersonal way become for me a matter of personal and intimate conviction. What I believe by faith, what I understand by the habit of theology, I possess and make my own by hope.

To consider persons and events and situations only in the light of their effect upon myself is to live on the doorstep of hell. Selfishness is doomed to frustration, centered as it is upon a lie.

Is there any more cogent indication of my creaturehood than the insufficiency of my own will? For I cannot make the universe obey me. I cannot make other people conform to my own whims and fancies. I cannot make even my own body obey me.

We must make the choices that enable us to fulfill the deepest capacities of our real selves. From this flows the second difficulty: we too easily assume that we are our real selves, and that our choices are really the ones we want to make when, in fact, our acts of free choice are (though morally imputable, no doubt) largely dictated by psychological compulsions, flowing from our inordinate ideas of our own importance. Our choices are too often dictated by our false selves.

Hence I do not find in myself the power to be happy merely by doing what I like. On the contrary, if I do nothing except what pleases my own fancy I will be miserable almost all the time. This would never be so if my will had not been created to use its own freedom in the love of others.

There is something in the very nature of my freedom that inclines me to love, to do good, to dedicate myself to others. I have an instinct that tells me that I am less free when I am living for myself alone. The reason for this is that I cannot be completely independent. Since I am not self-sufficient I depend on someone else for my fulfillment.

And a rational being who does not know what to do with himself finds the tedium of life unbearable. He is literally bored to death.

We ought to be alive enough to reality to see beauty all around us. Beauty is simply reality itself, perceived in a special way that gives it a resplendent value of its own. Everything that is, is beautiful insofar as it is real—though the associations which they may have acquired for men may not always make things beautiful to us. Snakes are beautiful, but not to us.

Art enables us to find ourselves and lose ourselves at the same time. The mind that responds to the intellectual and spiritual values that lie hidden in a poem, a painting, or a piece of music, discovers a spiritual vitality that lifts it above itself, takes it out of itself, and makes it present to itself on a level of being that it did not know it could ever achieve.

Since all true art lays bare the action of this same law in the depths of our own nature, it makes us alive to the tremendous mystery of being, in which we ourselves, together with all other living and existing things, come forth from the depths of God and return again to Him. An art that does not produce something of this is not worthy of its name.

The disheartening prevalence of false mysticism, the deadening grip that false asceticism sometimes gets on religious souls, and the common substitution of sentimentality for true religious feeling—all these things seem to warrant a little investigation of the subconscious substrate of what passes for “religion.”