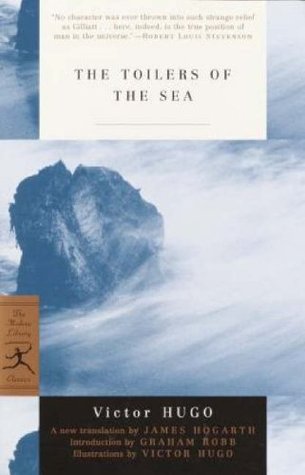

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Since then, Hugo’s vast oeuvre has effectively been whittled down to a few hundred pages. The Hunchback of Notre-Dame and Les Misérables are now the only visible peaks of a literary continent that comprises seven novels, eighteen volumes of poetry, twenty-one plays, a small museum of paintings and drawings, and approximately 3 million words of history, criticism, travel writing, philosophy, and coded diaries. Hugo would not have been surprised by this submersion of his work. All his novels end with images of erasure and decay. He knew that even masterpieces fall into disrepair and are

...more

Alessandra Souza liked this

Religion, society, nature: such are the three struggles in which man is engaged. These three struggles are, at the same time, his three needs. He must believe: hence the temple. He must create: hence the city. He must live: hence the plow and the ship. But these three solutions contain within them three wars. The mysterious difficulty of life springs from all three. Man is confronted with obstacles in the form of superstition, in the form of prejudice, and in the form of the elements. A triple ananke1 weighs upon us: the ananke of dogmas, the ananke of laws, the ananke of things. In Notre-Dame

...more

The Unknown sometimes holds surprises for the spirit of man. A sudden rent in the veil of darkness will momentarily reveal the invisible and then close up again. Such visions sometimes have a transfiguring effect, turning a camel driver into a Mohammed, a goat girl into a Joan of Arc. Solitude brings out a certain amount of sublime exaltation.

He returned two hours after Noguette133 had rung the curfew. This Brazilian bell rings at ten o’clock; so it was midnight.

It was a lodging for the kind of people who have no permanent lodging. In all towns, and particularly in seaports, there is always to be found, below the general population, a residue. Lawless characters—so lawless that even the law sometimes cannot get its hands on them—pickers and stealers, tricksters living by their wits, chemists of villainy continually brewing up life in their crucibles; rags of every kind and every way of wearing them; withered fruits of roguery, bankrupt existences, consciences that have declared themselves insolvent; the incompetents of breaking and entering (for the

...more

Dissimulation is an act of violence against yourself. A man hates those to whom he lies.

To be unmasked is a defeat, but to unmask oneself is a victory. It is an intoxication, an insolent and self-satisfied act of imprudence, a reckless display of nakedness calculated to insult all who behold it. It is supreme happiness.

Happiness and despair do not breathe the same air. A man in despair participates in the life of others from a great distance; he is almost unaware of their presence; he has lost any consciousness of his own existence; he is a thing of flesh and blood but feels that he is no longer real; he sees himself only as a dream.

Inanimate objects sometimes display a somber, hostile ostentation directed against man. There was defiance in the attitude of these rocks. They seemed to be waiting for something.

The sea is both open and secret; it hides, and is not anxious to divulge its actions. It brings about a shipwreck and then covers it over; it swallows up its victims out of a sense of shame. The waves are hypocrites: they kill, steal, conceal stolen property, plead ignorance, and smile. They roar, and then they bleat.157

It was one of those cases in which Jean Bart180 would have used the words he used to address to the sea each time he escaped shipwreck: “Cheated you, Englishman!” It is well known that when Jean Bart wanted to insult the ocean he called it the “Englishman.”