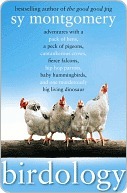

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

people carved pictures of birds on tombs as early as 2600 B.C.

they symbolize the soul.

bird-watching is the fastest-growing of all outdoor activities in the United States and one of the most popular hobbies the world around.

“Jewish penicillin,” chicken soup.

Like all members of the order in which they are classified, the Galliformes, or game birds, just-hatched baby chickens are astonishingly mature and mobile, able to walk, peck, and run only hours after leaving the egg. This developmental strategy is called precocial. Like its opposite, the altricial strategy (employed by creatures such as humans and songbirds, who are born naked and helpless), the precocial strategy was sculpted by eons of adaptation to food and predators. If your nest is on the ground, as most game birds’ are, it’s a good idea to get your babies out of there as quickly as

...more

But instinct is not stupidity.

Nor does instinct preclude learning.

We never determined how our first chickens knew their new home was theirs, either. We never knew how they managed to discern the boundaries of our property. But they did.

an average chicken can recognize and remember more than one hundred other chickens.

facial features

Because chickens live in flocks, the ability to identify individuals is even more important

Belonging is essential to a chicken’s well-being, as is clear from the complex social system of the pecking order.

The pecking order is not always a strai...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

When it comes to roosting at night, the pecking order determines who sleeps next to whom, and on which perch.

new babies

order arrives from Cackle Hatchery in Lebanon, Missouri—a box of live baby chicks, just hatched two days before.

imprinting.

Most newly hatched game birds, including turkeys, ducks, chickens, and geese, will follow the first moving object they see, which is usually, of course, their mother.

Chickens have been living with people for a very long time (by some reckoning, as long as eight thousand years—longer than donkeys and horses, longer than camels or ducks, and by some accounts, even longer than pigs and cattle).

Soon it became evident that some hens were consistently outgoing and others shy; some were loud and others quiet; some cautious and others reckless. This was particularly obvious whenever the hens faced a threat, such as a hawk flying overhead. Some hens hid in pricker bushes; others raced inside the coop. Some dashed behind a large board that leaned against an outside wall of the barn. Some individuals would continue to hide for more than an hour.

Chickens both remember the past and anticipate the future.

rooster called at a faster rate if the food discovered is especially tasty—like

chickens used several different alarm calls, depending on the size, shape, speed, and location of the predator.

We didn’t need a rooster to get our hens to lay (though only fertilized eggs will hatch), but a rooster has much to offer a flock. Hens can hope for no better protector than a good rooster. We can’t be in the yard with them every minute, but a rooster can, and he will fight to the death to protect his flock.

Most roosters are very solicitous of their hens. When he’s not patrolling for predators, he’s often searching for food his flock might enjoy.

None of our roosters stayed for long. The gentlemanly, long-tailed Lakenvelders, always pictures of vigorous health, dropped dead from their perches within days of each other before their second birthday.

Apparently their different physiologies make the males more likely to drop dead, a phenomenon we named Sudden Rooster Death Syndrome.

The Ladies, frankly, seemed somewhat relieved. Though they had appreciated their roosters’ food calls alerting them to particularly juicy worms or hidden treasure in the compost pile, there was a cost: the regular annoyance of someone jumping on your clean back with his dirty, scaly feet and biting your comb with his beak—whether you felt like it or not.

chickens will attack and even kill a wounded flock-mate is so well known that products have been developed to cope with it. One is called Stop Peck. It comes in a bottle like Elmer’s glue, looks like clotting blood, and to chickens, apparently, tastes awful.

red dot acts almost like a push button does for a machine, “releasing” an inborn, preprogrammed pecking response.

Yet sometimes, smart birds, capable of reasoning and forethought, are governed by an ancient, genetically determined program beyond their conscious control. Bird behavior is the product of both.

Why should chickens attack at the sight of blood? I haven’t found a fully satisfactory answer. Possibly because the sight of blood usually signals meat, a rare treat, which should be quickly eaten. Perhaps because a severely wounded flock-mate might attract predators—better to drive away one member than endanger the whole group. I don’t know.

Animal people are often accused of anthropomorphism, projecting human motives and emotions onto animals.

molts have always been subtle affairs, molting Rangers sport ugly red bald patches and itchy-looking areas where new pinfeathers are coming in. When one molts, often the others will try to exclude her from the coop.

“There is lack of pity in all birds,”

“Chickens have no sympathy. People can’t relate to it, so they don’t like it. It’s so...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

many birds still follow the dietary traditions of the carnivorous dinosaurs,

The mental demands of hunting prey in a complex environment may have driven the rise of intelligence among the dinosaurs who became birds.

frequencies below the threshold of human hearing. Such sounds are known as infrasound.

Many animals, including birds, almost certainly hear infrasound; birds might even use the infrasonic rumblings of the ocean or the shifting plates of the earth to help navigate on their migrations. But with few exceptions, like prairie chickens, most birds are too small to make infrasound. It takes a great deal of effort even for a bird as large as a cassowary.

Such low frequencies can travel over long distances; the sound is not dampened by the thick understory of wet leaves, as are high frequencies. This is why elephants and whales also use infrasound to communicate with one another when they are far apart.

Infrasonic communication also explains how whales find one another on migrations that span the globe to sites that vary from year to year.

And infrasound was probably also a perfect way for other very large individuals, living far apart from one another, in similar habitat: the dinosaurs.

Many dinosaurs—especially the duck-billed hadrosaurs—had tall, bony crests like the cassowary.

Hummingbirds

Birds are physiologically very different from us. Humans and our fellow mammals are fluid-filled creatures.

But birds, in order to be freed for flight, cannot afford to be loaded down with heavy fluids. Birds are made of air.

bones are hollow. Even their skulls are scaffolded with passageways for air. Their feather shafts are hollow, and the feathers themselves, like strips of Velcro, are interlocking barbules for catching air. Their bodies are filled with air sacs, which originate in, and function, in part, as extensions of the lungs. No fewer than nine of these filmy bladders fill the tiny body of a hummingbird: one pair in the chest cavity; another under each shoulder blade; another pair in the abdomen; one under each wing; and one along the neck.

Hummingbirds are the lightest birds in the sky. Of their roughly 240 species, all confined to the Western Hemisphere, the largest, an Andean “giant,” is only eight inches long; the smallest, the bee hummingbird of Cu...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.