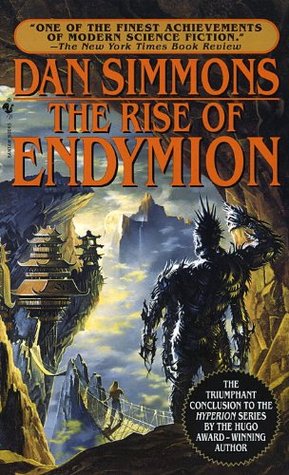

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Dan Simmons

Read between

September 15 - October 4, 2024

He had always distrusted people who asked to speak freely or who vowed to speak candidly or who used the expression “frankly.”

“Where is the bitch child?” asked the rescued female. She had once been known as Rhadamanth Nemes.

Federico de Soya sighed and closed his eyes. He felt like crying. Please, dear Lord, let this cup passeth from me. When he opened his eyes, the chalice was still on the altar and Admiral Marget Wu was still waiting. “Yes,” he said softly, and slowly, carefully, he began removing his sacred vestments.

“They’re shitting bricks,” I said. For years I’d avoided using my Home Guard vocabulary around the kid, but she was sixteen now. Besides, she had always used a saltier vocabulary than I knew. Aenea grinned. The brilliant light illuminated the sandy streaks in her short hair. “That’d be good for a bunch of architects, I guess.”

The Grand Inquisitor tilted his head ever so slightly to the left and Father Farrell waved two fingers over one of the console icons. The icons were as abstract as hieroglyphics to the untutored eye, but Farrell knew them well. The one he had chosen would have translated as crushed testicles.

Above the altar, Jesus Christ, his face stern and unrelenting, divided men into camps of the good and the bad—the rewarded and the damned. There was no third group.

Crusade. Glory. A final resolution of the Ouster Problem. Death beyond imagining. Destruction beyond imagining. Father Captain de Soya squeezed his eyes shut as tightly as he could, but the vision of charged particle beams flaring against the blackness of space, of entire worlds burning, of oceans turning to steam and continents into molten rivers of lava, visions of orbital forests exploding into smoke, of charred bodies tumbling in zero-g, of fragile, winged creatures flaring and charring and expanding into ash … De Soya wept while billions cheered.

“Aenea,” I said. “Yes?” “That’s really stupid. Do you know that?”

“Humans have been waiting for Jesus and Yahweh and E.T. to save their asses since before they covered those asses with bearskins and came out of the cave,” she said. “They’ll have to keep waiting. This is our business … our fight … and we have to take care of it ourselves.”

This night I had the flashlight laser that was our only memento of the trip out to Earth—set to its weakest, most energy-conserving setting, it illuminated about two meters of rain-slick street—a Navajo hunting knife in my backpack, and some sandwiches and dried fruit packed away. I was ready to take on the Pax.

For a long minute I said nothing. Rain pounded like tiny fists on closed coffins.

“Are you certain we’ll see each other there?” I shouted through the thinning rain. “I’m not certain of anything, Raul.” “Not even that we’ll survive this?” I’m not sure what I meant by “this.” I’m not even sure what I meant when I said “survive.”

It has been my experience that immediately after certain traumatic separations—leaving one’s family to go to war, for instance, or upon the death of a family member, or after parting from one’s beloved with no assurances of reunion—there is a strange calmness, almost a sense of relief, as if the worst has happened and nothing else need be dreaded.

From sunny Freude, populated by Pax citizens in elaborate harlequin fabrics and bright capes, the river took me to Nevermore with its brooding villages carved into rock and its stone castles perched on canyon sides under perpetually gloomy skies. At night on Nevermore, comets streaked the heavens and crowlike flying creatures—more giant bats than birds—flapped leathery wings low above the river and blotted out the comets’ glow with their black bodies.

Pain is an interesting and off-putting thing. Few if any things in life concentrate our attention so completely and terribly, and few things are more boring to listen to or read about.

I realized then what I had known since I was a child watching my mother die of cancer—namely, that beyond ideology and ambition, beyond thought and emotion, there was only pain. And salvation from it. I would have done anything for that rough-edged, talkative Pax Fleet doctor right then.

“What?” “Never mind. It will make sense when it comes about. All improbabilities do when probability waves collapse into event.”

Simply put, no battles were to be fought by mutual agreement. The seven archangels had been designed to descend upon the enemy like the mailed fist of God, and that was precisely what they were doing now.

“Now say a sincere Act of Contrition … quickly now …” When the whispered words began to come through the screen, Father Captain de Soya lifted his hand in benediction as he gave absolution. “Ego te absolvo …”

The air had grown thin and cold; the large cities had been plundered and abandoned; the great simoom pole-to-pole dust storms had reappeared; plague and pestilence stalked the icy deserts, decimating—or worse—the last bands of nomads descended from the once noble race of Martians; and little more than spindly brandy cactus now grew where the great apple orchards and fields of bradberries had long ago flourished.

The form was directly in front of her. Nemes had less than a ten thousandth of a second to phase-shift again as four bladed fists struck her with the force of a hundred thousand pile drivers. She was driven back the length of the tunnel, through the splintering ladder, through the tunnel wall of solid rock, and deep into the stone itself.

More than two hundred light-years from Mars System, Task Force GIDEON was completing its task of destroying Lucifer.

The thought made Hoag Liebler physically queasy. He disliked dying, and did not wish to do so more than necessary.

Where the hell was I? I lifted my wrist and spoke to the comlog, “Where the hell am I?”

The human mind gets used to strangeness very quickly if it does not exhibit interesting behavior.

“Rise, our son,” said the mass murderer of billions. “Stand and listen. We command you.”

To see and feel one’s beloved naked for the first time is one of life’s pure, irreducible epiphanies. If there is a true religion in the universe, it must include that truth of contact or be forever hollow.

To make love to the one true person who deserves that love is one of the few absolute rewards of being a human being, balancing all of the pain, loss, awkwardness, loneliness, idiocy, compromise, and clumsiness that go with the human condition. To make love to the right person makes up for a lot of mistakes.

Without God, the universe can only be a machine … unthinking, uncaring, unfeeling.” “Why?” said the boy.

Sol saw that love was a real and equal force in the universe … as real as electromagnetism or weak nuclear force. As real as gravity, and governed by many of the same laws.

Artists recognize other artists as soon as the pencil begins to move. A musician can tell another musician apart from the millions who play notes as soon as the music begins. Poets glean poets in a few syllables, especially where the ordinary meaning and forms of poetry are discarded.

Only humankind struggles and fails in becoming what it is. The reasons are many and complex, but all stem from the fact that we have evolved as one of the self-seeing organs of the evolving universe. Can the eye see itself?”

“There is no guarantee of happiness, wisdom, or long life if you drink of me this evening,” she says, very softly. “There is no nirvana. There is no salvation. There is no afterlife. There is no rebirth. There is only immense knowledge—of the heart as well as the mind—and the potential for great discoveries, great adventures, and a guarantee of more of the pain and terror that make up so much of our short lives.”

“Death is never preferable to life, Raul, but sometimes it’s necessary.”

The problem with being passionately in love, I thought, is that it deprives you of too much sleep.

The Grand Inquisitor’s face was still bloodied. His teeth were bright red as he screamed. His eye sockets were ragged and void, except for tendrils of torn tissue and rivulets of blood. At first, Captain Wolmak could not discern the word from the shriek. But then he realized what the Cardinal was screaming. “Nemes! Nemes! Nemes!”

The three of us flew as close as we could, blue delta, yellow delta, green delta, the metal and fabric of our parawings almost touching, more fearful of losing one another and dying alone than of striking one another and falling together.

“I got my message down to thirty-five words. Too long. Then down to twenty-seven. Still too long. After a few years I had it down to ten. Still too long. Eventually I boiled it down to two words.” “Two words?” I said. “Which two?”

“Choose again,” said Aenea.

“Almost everything interesting in the human experience is the result of an individual experiencing, experimenting, explaining, and sharing,” said my young friend. “A hive mind would be the ancient television broadcasts, or life at the height of the datasphere … consensual idiocy.”

Aenea nodded. “It’s wonderful to preserve tradition, but a healthy organism evolves … culturally and physically.”

“Now,” said Nemes. She stepped toward Aenea. I stepped between them. “No,” I said, and raised my fists like a boxer ready to start.

Pain never stopped me. I certainly felt it, but it never stopped me.

The sandwiches were large and thick. She set them on catch-plates made of some strong fiber, lifted her own meal and a beer bulb, and kicked toward the outer wall. A portal appeared and began to iris open. “Uh …” I said alertly, meaning—Excuse me, Aenea, but that’s space out there. Aren’t we both going to explosively decompress and die horribly?

Aenea … Aenea.” A prayer. My only prayer then. My only prayer now.

Centuries ago—as far back as the twentieth century A.D.—human researchers dealing with similar neural networks comprised of pre-AI silicon intelligences discovered that the best way to make a neural network creative was to kill it. In those dying seconds—even in the last nanoseconds of a sentient or near-sentient conscience’s existence—the linear, essentially binary processes of neural net computing jumped barriers, became wildly creative in the near-death liberation from off-on, binary-based processing.

A. Bettik stopped me with a hand on my wrist. “M. Endymion,” he said softly, “if love is the human emotion to which you refer, I feel that I have watched humankind long enough during my existence to know that love is never a stupid emotion. I feel that M. Aenea is correct when she teaches that it may well be the mainspring energy of the universe.”

“Yeah,” I said, not knowing what I was agreeing to. “I’ll come along.”

“Can you imagine, Raul? Millions of the space-adapted Ousters living out there … seeing all that energy all the time … flying for weeks and months in the empty spaces … running the bowshock rapids of magnetospheres and vortexes around planets … riding the solar-wind plasma shock waves out ten AUs or more, and then flying farther … to the heliopause termination-shock boundary seventy-five to a hundred and fifty AUs from the star, out to where the solar wind ends and the interstellar medium begins. Hearing the hiss and whispers and surf-crash of the universe’s ocean? Can you imagine?” “No,” I

...more

“Choose again,” said Aenea. And she turned, walked away from the podium, and went down to where the chalices lay on the long table.