Sadeqa Johnson on the Power of the Stories That Find You

Posted by Cybil on February 1, 2026

Sadeqa Johnson doesn’t go looking for stories. Stories find her.

The New York Times bestselling author of The House of Eve was walking the Richmond slave trail when the story of Mary Lumpkin, who became the inspiration for Yellow Wife, found her. And a simple Google search served up the inspiration for her latest novel, Keeper of Lost Children.

“I popped ‘orphans’ or ‘adoption’ or ‘unwed homes for mothers’ into my search, and the story of Mabel Grammer and the Brown Baby Plan popped up in my feed,” she says of the real-life inspiration behind her latest novel.

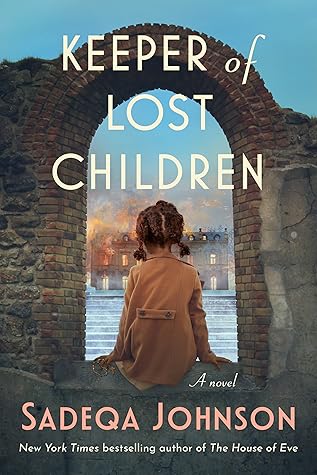

A deftly woven historical fiction, Keeper of Lost Children follows the interconnecting lives of Ozzie, Sophia, and Ethel through the events and aftermath of World War II in a story that explores freedom, identity, and American culture.

Ethel Gathers is stationed with her husband in Manheim, Germany, where she discovers an orphanage for mixed-race children. Around the same time, Ozzie Phillips, a Black man serving overseas in the recently desegregated U.S. Army, falls for Jelka, a German woman with a secret. Years later, teenager Sophia Clark is plagued by nightmares of events she can’t remember and begins to question her past.

Johnson spoke to Goodreads contributor April Umminger about self-publishing, her calling as a writer, strong women who need their stories told, and the Keeper of Lost Children. Their conversation has been edited.

The New York Times bestselling author of The House of Eve was walking the Richmond slave trail when the story of Mary Lumpkin, who became the inspiration for Yellow Wife, found her. And a simple Google search served up the inspiration for her latest novel, Keeper of Lost Children.

“I popped ‘orphans’ or ‘adoption’ or ‘unwed homes for mothers’ into my search, and the story of Mabel Grammer and the Brown Baby Plan popped up in my feed,” she says of the real-life inspiration behind her latest novel.

A deftly woven historical fiction, Keeper of Lost Children follows the interconnecting lives of Ozzie, Sophia, and Ethel through the events and aftermath of World War II in a story that explores freedom, identity, and American culture.

Ethel Gathers is stationed with her husband in Manheim, Germany, where she discovers an orphanage for mixed-race children. Around the same time, Ozzie Phillips, a Black man serving overseas in the recently desegregated U.S. Army, falls for Jelka, a German woman with a secret. Years later, teenager Sophia Clark is plagued by nightmares of events she can’t remember and begins to question her past.

Johnson spoke to Goodreads contributor April Umminger about self-publishing, her calling as a writer, strong women who need their stories told, and the Keeper of Lost Children. Their conversation has been edited.

Goodreads: I was surprised to learn that this book is based on an actual initiative from World War II, the Brown Baby Plan, and the life of Mabel Grammer. How did you discover her story and come up with the idea to write Keeper of Lost Children?

Sadeqa Johnson: When I really need to get into the story, I'll go away from anywhere between 4 days to 10 days. I was at this space in Virginia called the Porches, and I was there to write The House of Eve. I was doing research, and I popped into my Google search something like “orphans” or “adoption” or “unwed homes for mothers,” and somehow this story popped up in my Google feed.

I'm a firm believer that stories find me, that I have to just be open and be ready to receive them. I don't have another way to say how I discovered the story. It really found me.

I saw this documentary film called Brown Babies: The Mischlingskinder Story; it was a documentary that was done by Regina Griffin. I learned about Mabel Grammer, this Black woman who was a journalist and a socialite. She got married to an army chief warrant officer and went over to Germany with him. She couldn't have children of her own, and while she was there, she discovered these mixed-race children and orphanages. The movie goes on into individual lives, and she tells the bigger, broader story of Mabel Grammer, the Brown Babies, and what it was like for some of them who came over to America.

I feel like there's such a chunk of our American history, Black American history, women's history, that's left out of our educational narrative. I thought, “My gosh, this woman needs a story.”

I jotted some notes down to myself—gave myself 15 minutes to write down everything I was thinking and then went back to writing The House of Eve. I left myself some good breadcrumbs, and then I put it away, and I went back and I finished The House of Eve. But that was how I found the story.

GR: How did you decide to structure this novel?

SJ: For The House of Eve, I wrote two characters, two points of view, every other chapter that a b, a b, a b. I thought it would be a real challenge to do three characters for Keeper of Lost Children.

I wanted to tell the story of Mabel Grammer, which inspires the character Ethel Gathers. Then, my great uncle was in the Air Force in the 1930s or ’40s. I remember him telling me stories about what it was like for him going overseas during Jim Crow America—there was so much more freedom for Black men in Europe. I thought, no one tells the story of the Black GI and what his experience was during the Double V campaign.

I always think the Black man needs a publicist. I have wonderful Black men in my life—my husband, my father, my son—and what I see on TV, it never reflects that. I felt really drawn to tell his side of the story, so much so that it became almost Ozzie's book.

Then, I tend to always have this young character in my stories, this 15- to 17-year-old girl who is in a situation and she's trying to get out of it. She wants education, she wants freedom, she wants to make something of her life, but there's all these things holding her back. That was how Sophia got into the story.

As I was researching that time period, I discovered that school integration and Brown v Wade happened in the ’50s, but that was just for public school. No one talks about private schools and private boarding schools and what that looked like, which didn't happen until the mid to late ’60s.

I was telling one complete story, and it was one book. The difficult part was making all three characters coherent and enough where you were in their individual stories. Halfway through, I kept asking myself, “What did you get yourself into?!”

GR: Well, it was very well structured—you would never know, as a reader, that you had any sort of struggle with it. Among the three characters—Sophia, Ethel, and Ozzie—who was the most difficult to write?

SJ: Take a guess, and then we'll see if you get it right.

GR: I will guess Sophia—teenage orphan and all that?

SJ: It was Ethel. When I first started off, I was trying to follow Mabel Grammer’s story to the T. Everything that I found out was that she was just so saintly, and so giving, and she just cared about these brown babies so much that she really gave her life to making sure that they found homes. I didn't know how to fictionalize that in a way that your fingers were burning to turn the page to know what happened next. She hit a lot of roadblocks in getting these children adopted, but there wasn't much juice and drama for me to pull from.

I started off thinking I was going to call her Mabel, but that wasn't working at all. Once I changed her name to Ethel Gathers and made her fictional, it gave me more room to be creative. It was she who the story was inspired by, and the first introduction to this world, but my fictional characters, Ozzie and Sophia, just proved to be a lot easier for me to write.

GR: That makes a lot of sense—the pressure of history and getting it right, versus creating a character that's all your own. How do you do your research? Did you interview any of the Brown Baby Plan orphans or anyone associated with the program?

SJ: I didn't interview any of them, but I read books. There was one penned by a gentleman who was a Brown Baby, so I read that. There were interviews on YouTube. There was also the German Brown Baby Alliance, where I would go onto their social media page and read different things. There are other people who've given talks on this part of history, so I would watch the lectures. I was able to find a lot of newspaper clippings that happened during that time. There was an article in Ebony magazine and Jet magazine. Then Mabel Grammer, herself, was a journalist. I went to the Library of Virginia and pulled articles that she had written about the Brown Baby Plan and about adopting her 12 children. That was how I was able to figure out what that time period felt like and to bring her voice into the story.

GR: How did you pick the years that you used as your points of departure? You span decades in the lives of these characters—how did you pick those?

SJ: Well, I was thinking about the birthdates of the Brown Babies, in general. That's how I was able to set Ethel and Ozzie’s chapters, so that they would make sense. Also, I looked at when Mabel Grammer was in Germany. I wanted to stay as close to her story as possible. The desegregation of the armed forces was also another important part of the story, because, while it happened in words and language and on paper, it didn't really change the lives of the Black Americans who were serving. That was another point.

With Sophia's story, it was two things—the thing with Sophia was I wanted Willa from The House of Eve to come and be her roommate.

GR: Oh, that's so cool. I love that you interconnected that character from your other book!

SJ: I don't normally write sequels, and that was my way of giving you a glimpse into The House of Eve without writing a sequel. So I needed Willa and Sophia's ages to be around the same. I didn't want people to flip back to The House of Eve and have years that didn't match.

That was one, and then, two, I wanted to make Sophia's character integrating the boarding schools around the time when it actually happened. Those two events pushed her into the 1960s, while why Ozzie and Ethel were late 1940s and ’50s.

GR: In terms of the way that you start your sections, how did you pick the quotes that you use?

SJ: I'm always looking for a quote that is going to frame that section of the story. I'm not giving anything away, but I'm giving the reader something to expect. I’m setting the tone. When I first started writing, I would title each chapter for the same reason. I stopped doing that because it's a lot to title each chapter, but it gave me a framework what I was trying to work with.

GR: That brings me to another question: In general, how did you start writing? Have you always written since you were little or kept a diary or what?

SJ: I have a diary here on my shelf that goes back into the 1980s—my very first diary. I've always kept a diary. I was a big reader, and writing was a hobby. Some kids color; I would make up stories. I was in seventh grade, and I wrote a research paper for a contest, and I won that contest. It was the first time I thought that I'm good at constructing these sentences and making it say something that matters.

When I graduated college, my first job was in publishing. I worked at Scholastic, and then I worked at GP Putnam's Sons, in the publicity department. I was surrounded by books, and it reignited my love for telling stories. It was there that I started working on my first novel, right out of college. It didn't go anywhere—I don't even know if I finished it—but it was my second novel, Love in a Carry-On Bag, which is my first published book. It was self-published because I wasn't able to get a publisher to back me up on that one.

GR: I read that about your career—that you self-published when you started writing. I think people don't fully understand how difficult it is to get an agent and actually get a book published. How did you go from self-published to being backed by a publishing house?

SJ: Because I worked in publishing, I had a few relationships with editors and agents. I really thought it was going to be 1-2-3, easy. I thought I write that first book, and next thing you know, I'm on the New York Times bestsellers list.

GR: Which did eventually happen, though not with that book…

SJ: [Laughs.] “Stay the course,” for sure. “Stay the course, writer, stay the course.”

My husband convinced me to start a little small press when my agent couldn’t get it published. We literally went up and down the East Coast selling Love in a Carry-On Bag out of our trunk, at every book festival, every hair show—any place we thought that people who read books were going to be.

Once I went through the self-publishing process and realized my own worth as a writer and what I was bringing to the literary world, when we went back out that second time, my ask was different. It was I want to have a relationship with a publisher who believes in my vision. I want to have choice. I want to have a partnership and a conversation on how my career is going to move forward.

I had three editors who wanted to purchase my second book, Second House from the Corner, and I was able to sit down and decide who I wanted to be in business with, as opposed to “please pick me, anybody.”

That shift in consciousness has made a difference in the trajectory of my career.

GR: What advice do you have for someone starting out without connections, completely green and new to the industry?

SJ: The first thing I would say is get to writing that book!

When I first started, I thought: “Draft one, book is ready. Let's go! Draft two, book is ready. Let's go!” At draft two, the book is not ready.

Spend the time. It got under my skin when people said this to me, but it is true. We want overnight success, but sometimes we're not ready for overnight success. Spend the time developing your craft, your voice as a writer, make a commitment to yourself, whether it's 30 minutes a day where you say, “This is my time for writing,” and you keep showing up for yourself. If you keep showing up, the writing will develop.

And then, when you feel like you've really done all you can do, find a librarian friend or book club friend to give you feedback. Find a developmental editor to check everything before you start shopping it with agents. Because once you start querying agents, they're only going to tell you “no” one time.

GR: You talked about showing up for your craft—you didn't start out writing historical fiction. Was the shift in subject matter a process and an evolution that you went through? What led to the shift from chick lit to something more serious?

SJ: It was a calling. I was in my kitchen in Springfield, New Jersey, and I heard a voice that said, “Move.” That was February of 2015, and by June of 2015 we had moved from New Jersey to Richmond, Virginia.

Nine months later, we were on the Richmond slave trail, and I discovered the story of Mary Lumpkin, which was the inspiration for Yellow Wife. I remember the hairs on my arms standing up; everything in my body was like, “You need to be paying attention.”

I kept thinking, “This is such a good story, but this is not a story that I want to write. I'm not qualified. I'm not a historian; I'm not a historical fiction writer.”

But it felt like the ancestors had another plan for me. They got in the car with me and followed me home, and they kept pressing me and touching me and pushing me and nudging me toward that story. Once I said yes to it, it just all started to happen, and I was writing historical fiction. It wasn't a choice. It was really that this story chose me.

I now see myself as a writer whose job or mission is to go into some of these dark spaces in history and pull out ambitious women—women who we've forgotten about, women who have been marginalized, women whose stories have been buried—and bring them to light, and do it in fiction so that it's accessible to all.

GR: I want to say this is the second book where you've dealt heavily with identity and mixed-race issues, with Yellow Wife and also with Keeper of Lost Children . Why do you think it's important to share those perspectives and that history?

SJ: When I go back to what we see on television about Black culture and Black lives, it’s not true—it's not a reflection of who we really are. Black culture and Black people are a melting pot. Identity is something that we're always searching for and trying to make sure that it's seen truthfully.

I'm always exploring class culture, socioeconomics, and all the things that make up our American culture. But then I bring it into the smaller lens of what it is like for Black Americans, and there's always been mixed-race children.

I tell my children: Everything goes back to slavery and Stevie Wonder. [Laughs.]

When you go back to slavery, with Yellow Wife, her being mixed race was a part of what that culture was. It's the same for Keeper of Lost Children . When two groups of people get together, no matter what you say, you can't keep them apart. We're all this melting pot, and I like exploring it and what it is like for all of us.

GR: What are the other themes that are important to you when you're developing stories?

SJ: Some of my themes, usually, are freedom, identity, class, culture. In this book, I deal with alcoholism, and I've dealt with addiction in a few of my books. Love and what family is are also another constant theme in my novels. I'm not really the “best friend” writer—it’s family structure, and there's always been an ambitious woman at the center of my story, trying to make a change. She's never the same person by the time you get to the last page.

GR: You mentioned addiction and Ozzie with his struggle with alcohol. That was an unexpected part of the story for me, but looking back, I could see it threaded through. What made you put that sub-storyline in there?

SJ: I was thinking, secrets make you sick. This was the disease that was developed from his secrets. I think people don't look at alcohol, drug abuse, opioids, all of that. I wanted to open up that conversation if that's in your family, or if this is something you've experienced, it's OK. This is what Ozzie’s gone through, and this is how he found his way out of it. I always want to give some sort of hope, some sort of lesson, to my readers. In the same way if you go away from my historical fiction novels and you're looking up those bits of history, then you can go away and do some research on this, too, and find help for yourself or for a loved one.

GR: I love that. And then, what is the most fun part for you writing a book like this and writing in general. What do you like best about your job?

SJ: I like getting lost in the story. I love when I'm so lost in my world that time just seeps away because I'm so engaged with my characters. It's like I'm living this other life because I see myself as a conduit, like the characters are coming through me.

GR: What authors are your favorite and why?

SJ: I always go back to some of the classics—Maya Angelou, Zora Neale Hurston, Terry McMillan. I go back to the books that inspired me when I was first starting out as a reader. I was reading Maya Angelou in high school. Terry McMillan's first book, Mama, was the first time that I saw myself in a story, because all the other characters that I had read growing up were white characters.

The first time I read Their Eyes Were Watching God I was completely transformed into this world that I didn't even know existed. And there were Black Americans living this life. Those are the stories that I think about. I want to leave a legacy the way those writers left the legacy for me. I want to open the door for the writers behind me to feel like, “Well, if Sadeqa can do it, I can study her work and do it as well.”

GR: What books are you reading now?

SJ: I finished Broken Country by Clare Leslie Hall, and that book just gutted me in all the best ways. Her book made me feel like I want to write again. Historical fiction, Victoria Christopher Murray did an amazing job with Harlem Rhapsody, and was, again, bringing to the forefront a woman that we didn't know as part of our history, Jessie Redmon Fauset. Why are we not learning about Jessie Redmon Fauset in our history classes, in our literature classes? I just finished the book We Don't Talk About Carol by Kristen L. Berry. I don't read debuts a lot, but it was something about that one that pulled me in.

GR: This title, Keeper of Lost Children, is perfect for this story, but did you think about others?

SJ: When I sold the book, it was called "Beautiful Children," but my U.K. publisher thought it was a little too soft. I keep a Google Doc with anything that pops in my mind as I'm researching, and when my publisher and I got together, we can look at that and start floating titles around. Keeper of Lost Children , I don't think it was perfect, but we pieced it together and it is a version of "Beautiful Children."

GR: Last question: What's one thing that I haven't asked or that you'd want readers to come away with after reading this?

SJ: I'm always thinking about the strength of our ancestors when I'm writing books, and I'm always overwhelmed by the knowledge of how hard they had to work to accomplish things that I now get to benefit from. If Mabel Grammer could go into the German courts without speaking a lick of German, and get it approved for these more than 500 children to be adopted, then I can't complain about anything. To keep the drive, the will, the never giving up, and that anything is possible. I think the important thing is that we all stand on the shoulders of very ambitious and hungry women who will go to any lengths to make lives better for children, to make lives better for all of us.

Sadeqa Johnson's Keeper of Lost Children will be available in the U.S. on February 10. Don't forget to add it to your Want to Read shelf. Be sure to also read more of our exclusive author interviews and get more great book recommendations.