Exclusive: Larry McMurtry on the Last of the Cowboys

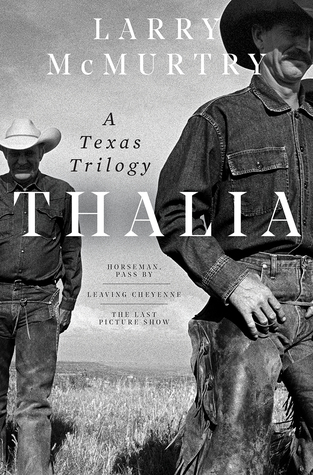

While Larry McMurtry is largely known by younger generations for his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Lonesome Dove, it is his first three novels—Horseman, Pass By, Leaving Cheyenne, and The Last Picture Show—that brought him to national prominence and boldly injected realism into American literature. This trilogy, Thalia, is being re-released for the first time this month along with the following new introduction by the author, which was given exclusively to Goodreads to excerpt:

Life and art alike are filled with accidents. The big one in my career was the discovery, by chance, of William Butler Yeats, the great Irish poet, and his famous epigraph:

On life, on death.

Horseman, pass by!

Had I not stumbled upon those words, I have often wondered whether I would have written Horseman, Pass By. It was, for me, the key that turned the starter to my journey as a writer. I went home to Archer City in 1958, the summer after I graduated from North Texas State University in Denton, Texas, to cowboy on my father's ranch while I wrote the book.

I had little previous experience in writing fiction, but I jumped right into Horseman. The novel grew out of a short story I had written in the only creative writing class I attended while at North Texas State, which was about the decline and death of a famous Panhandle cattleman. It was probably my first intimation of Charles Goodnight, the great Panhandle cattleman himself. My father's own family produced nine cattlemen, who were sprinkled all over the Texas Panhandle. In all, I did five drafts, written at a five-pages-a-day pace. Once my fluency was established, I occasionally doubled that pace, but the five-pages-a-day is the one that has served me throughout most of my writing life. I finished Horseman about a week before I left Archer City for Houston, Texas, where I was about to enroll at Rice University as a graduate student in English.

Looking back, I realize that completing Horseman, Pass By marked the end of my direct contact with the myth of the cowboy—or at least, the myth carried throughout their lives by the cowboys I knew. My father was one of those cowboys. I myself have carried that myth through more than forty books. I didn't know where the completion of that first novel might lead, but I did know, once I finished it, that my life was to be spent with words.

Leaving Cheyenne, written a few years after my first novel, is, in my estimation, a vast improvement over the occasionally pleasing lyricism of Horseman, Pass By. At the very least, I like to feel that in Leaving Cheyenne, I had matured as a writer. It tells the bittersweet story of a longtime love triangle among a rancher, his cowboy, and an appealing countrywoman who loves them both. It might be generous to call it my American version of Jules et Jim, Francois Truffaut's lively masterpiece that tells the same story in French.

The Last Picture Show, the third book contained in this Thalia trilogy and originally published in 1966, was written while I was teaching freshman English at Rice University in Houston. It was written in order to teach myself how to write fiction in the third person. I wrote it in the first person and then painstakingly translated it into third person. The Last Picture Show is mostly known by the brilliant movie (written mostly by me and Polly Platt) directed by Peter Bogdanovich. Polly, Peter's wife at the time, had read the novel, loved it, and then pestered her husband to read it and consider adapting it into a film. She had multiple roles on the movie, including production design, makeup, and helping Peter find its brilliant cast. Polly and I remained close long after the film ended and up to her death in 2011.

The novel takes place in a small town in 1950s Texas I called Thalia, much like the small town where I grew up, but that small town might live anywhere within the vastness of this great United States. The movie house in Archer City burned down in the 1950s, when the population was less than two thousand people—the same census number today. The closing of the picture show in a place already isolated from the outside world would undoubtedly intensify, both intellectually and emotionally, that sense of isolation.

After World War II, much of America began an exodus from the small towns to the cities. And so the myth of the cowboy grew purer, because there were so few actual cowboys to dispel it. While writing these three novels, it was clear to me that I was witnessing the dying of a way of life, too—the rural, pastoral way of life. And in many of the books that I've produced, it has taken thousands of words to attend, as best I could, to the passing of the cowboy as well: the myth of my country, and of my people, too.

—Larry McMurtry

The above excerpt was reprinted from Thalia by Larry McMurtry © 2017 by Larry McMurtry. Used with permission of the publisher, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Check out more recent blogs:

The 21 Big Books of Fall

September's Hottest Books

Readers' Favorite Quotes from The Catcher in the Rye

Comments Showing 51-57 of 57 (57 new)

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

I have read everyone of his books and think he is the greatest least -appreciated author of his time. Lonesome Dove is my favorite book - there is no better cast of characters ever created. It is the one book I have insisted all my children read and noone has been disappointed. The mini-series is also as good as a book adaptation can be and worth a 6 hour binge.

I have read everyone of his books and think he is the greatest least -appreciated author of his time. Lonesome Dove is my favorite book - there is no better cast of characters ever created. It is the one book I have insisted all my children read and noone has been disappointed. The mini-series is also as good as a book adaptation can be and worth a 6 hour binge.

Gary wrote: "Well said, Egon. His contribution to Western/South-Western American culture is difficult to overstate."

Gary wrote: "Well said, Egon. His contribution to Western/South-Western American culture is difficult to overstate."He did win a Pultzer for Lonesome Dove!

Thank you for sharing this excerpt. I absolutely loved Lonesome Dove but was not aware of this trilogy. I'll be adding these books to my "want-to-read" list.

Thank you for sharing this excerpt. I absolutely loved Lonesome Dove but was not aware of this trilogy. I'll be adding these books to my "want-to-read" list.

Second to that!