PHARAOH: firepower in the desert, 1884

The video below shows me shooting an 1882 Martini-Henry rifle, the weapon used in my novel Pharaoh by British troops against the forces of the Mahdi during the 1884-5 expedition to relieve General Gordon in Khartoum. That war was one of the last major conflicts fought using black powder, though with fast-action breech-loading rifles far superior to the muzzle-loading weapons that had been the mainstay of armies only twenty years previously. With reloading now taking only seconds, these new rifles allowed a disciplined force to lay down a withering fire almost as devastating as machine-guns were to be in wars to come; their accuracy also meant that sniping, or ‘sharpshooting’ as it was called, was now possible at ranges that were previously impossible, allowing my protagonist Major Mayne to use one of these rifles to pick off a dervish rifleman across the Nile more than 600 yards distant.

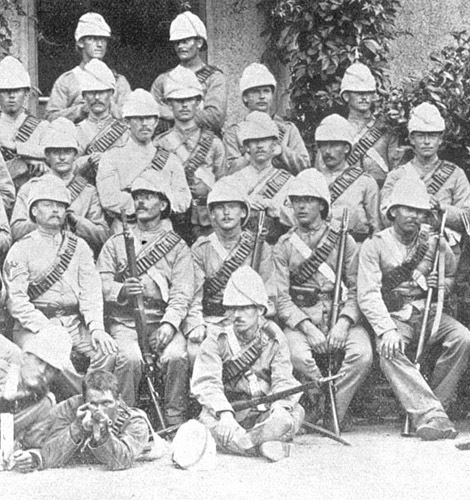

A rare photo from the 1884-5 Nile campaign showing troopers of the 11th Hussars in desert gear with Martini-Henry rifles.

Cartridges compared: .577/450 Martini-Henry, .303 Lee-Enfield and .22 LR.

The Martini-Henry disassembled, with Pattern 1876 bayonet as used in the Sudan.

The Martini-Henry fired a massive 480 grain .45 calibre bullet, projected by 85 grains of Curtis and Brown powder in a .577 bottle-shaped cartridge. The British experience fighting ‘fanatics’ during the Indian Mutiny of 1857-8 had led them to favour rifle and pistol rounds with maximum stopping power, and the .577/450 was the most powerful they ever adopted. The rifle action was an immensely strong ‘falling block’ actuated by a trigger-guard lever; pulling down the lever ejected the spent cartridge and opened the breech for the next round, and closing the lever raised the block and cocked the action. As a single-shot military rifle it was unrivalled, its main drawbacks being the problems inherent with black powder of excessive fouling and barrel overheating – problems only alleviated with the introduction of smokeless nitro propellants from the late 1880s, at a time when the Martini-Henry was rendered obsolete in British service by the introduction of the bolt-action .303 rifle that was to become the Lee-Enfield. Despite this, the Martini-Henry in a .303 version continued in use by colonial troops until well into the 20th century, and in Afghanistan was seen alongside Lee-Enfields in the hands of tribesmen as late as the Soviet war of the 1980s.

The Remington rolling-block rifle, with its breech open.

The Egyptian and Sudanese soldiers on the Nile were not armed with Martini-Henrys but instead with US-made Remingtons, ordered by the Egyptian government in the late 1860s. Chambered in .43 Egyptian, the Remington ‘rolling block’ was another ingenious breech-loading design: the block was a drum of steel that was snapped shut over the breech once it was loaded, and then locked tight when the trigger was pulled and the hammer closed over the drum before striking the firing pin. As the operation require three steps - manually cocking the hammer, thumbing open the block and then closing it - the Remington was a slower weapon to reload than the Martini-Henry, and the .43 Egyptian was a slightly less powerful cartridge. Nevertheless, it was an excellent, robust rifle, over a million being produced in various calibres by the Remington factory in New York State, providing rifles for buffalo-hunters in the American west – where it vied with the Sharps rifle - as well as for the many countries that adopted it as their military arm, including Egypt, Spain and Norway. Its widespread use across north Africa was a matter of ready availability, but it may also have been favoured by tribesmen because its distinctive shape in the grip area was similar to the slender flintlock and snaphaunce rifles that had been their mainstay in earlier decades, and continued in use well into the 20th century.

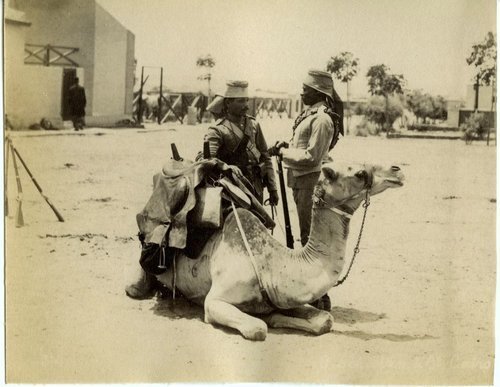

Egyptian soldiers in the late 19th century with Remington rifles.

Remingtons were also used against the British by Mahdist warriors who had picked up rifles from the battlefield. In 1883, before Gordon was appointed to Khartoum, the Egyptian governor of Sudan hired a former Indian army officer named William Hicks, remembered as ‘Hicks Pasha’, to lead a ragtag force of Egyptian and Sudanese troops - an army described by Winston Churchill as ‘the worst in the world’ – against the Mahdi, a doomed enterprise that resulted in their annihilation at the battle of El Obeid and thousands of Remington rifles falling into dervish hands. The dervishes are remembered from later battles such as Abu Klea for their suicidal charges and ferocity in hand-to-hand combat, but they had also became proficient marksmen and their Remingtons were responsible for the deaths of many hundreds of British, Egyptian and Sudanese government troops during the campaign.

Egyptian markings stamped into the barrel of the Remington.

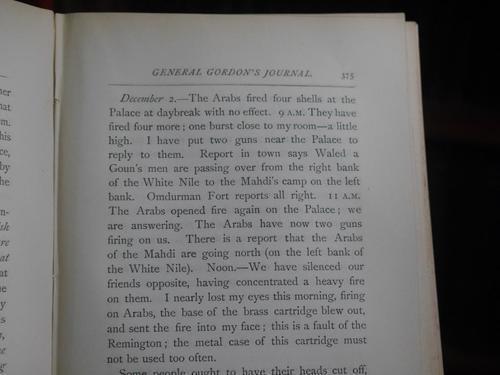

The Remington held by my nephew in these pictures well may be one of those rifles, its original Egyptian ownership revealed by the markings in Arabic script stamped above the breech. The lands of the rifling are worn down from extensive use, though the bore itself is shiny and well looked after - as would have been the case not only for government troops but also for Mahdist warriors well aware of the corrosive effects of black powder fouling if left uncleaned. I haven’t tried to fire this rifle as it has a slight loosening of the breech block; I’m mindful of General Gordon’s accident with a Remington while sniping at the enemy over the Nile, recounted in his diary entry opposite. The fault that he identifies was probably not with the rifle or with the cartridge but with the fact that his troops had reloaded the brass too often and weakened it, factory ammunition no longer being available to the beleaguered garrison. Nevertheless, unlike the British authorities in London who had turned a deaf ear to his warnings about the rise of the Mahdi, I’m inclined to heed his experience with the Remington and leave this rifle well alone, its potency for me lying instead in the episode of history that it represents and the ongoing ramifications of the Mahdi war in that part of the world today.

newest »

newest »

Al Sumrall alsumrall2001@yahoo.com

author: Battle Flags of Texans in the Confederacy 1995

co author: Old Hoodoo: America's First Battleship (1895-1911)

Current project (research complete): The Potato Digger: The Colt/Browning 1895 Machine Gun and Later Variants