Siavahda's Blog, page 100

May 14, 2020

There is beauty in truth: The Dragon’s Legacy by Deborah A. Wolf

phoenix art credit Sujono Sujono

The Dragon's Legacy (The Dragon's Legacy #1) by Deborah A. Wolf

Representation: Characters of Colour, Non-Traditional Gender Roles

on 4th April 2017

Genres: Epic Fantasy

Buy on Amazon, The Book Depository

Goodreads

The last Aturan King is dying, and as his strength fades so does his hold on sa and ka. Control of this power is a deadly lure; the Emperor stirs in his Forbidden City to the East, while deep in the Seared Lands, the whispering voices of Eth bring secret death. Eight men and women take their first steps along the paths to war, barely realizing that their world will soon face a much greater threat; at the heart of the world, the Dragon stirs in her sleep. A warrior would become Queen, a Queen would become a monster, and a young boy plays his bird-skull flute to keep the shadows of death at bay.

For my first Wyrd and Wonder review, I wanted to talk about one of my favourite books in all the world.

The problem is that I have no idea how to describe it.

Wolf has created an entirely new world that, while lacking the true otherness of, say, one of Karen Healey’s settings, is a strange and beautiful – and brutal – place that’s all too easy to get lost in. It’s a world where the sun is a dragon and his mate slumbers under the earth, kept asleep by the life-sapping magic sung by the Aturan rulers lest she break the planet like an egg by waking. It’s a world where the vash’ai, sapient, telepathic tusked tigers, forge psychic bonds with the worthiest of the Zeeranim, the matriarchal warrior-people who share the desert with them. It’s a world where women lie down with otherworldly beings to provide their Emperor with daeborn children for his armies. It’s a world that was almost destroyed by the cataclysmic Sundering a thousand years ago, and which is still feeling the effects when the story opens.

The worldbuilding is phenomenal. Although the Sindanese empire is vaguely reminiscent – at least to this white, Western reader – of East Asia, it’s a very passing and superficial resemblance; similarly, the Zeeranim might remind you of the Amazons, but only because that’s where all minds jump to when you hear ‘women warriors on horseback’ – they are entirely their own people. (And damn, do they have men.) And while this might not be a Healey world, it’s still got that deliciously dizzying factor as you’re thrown into the midst of cultures that don’t pull any punches – Wolf expects you to hit the ground running as the reader is inundated with alien terminology and phrases – like ehuani, a word that means there is beauty in truth, a concept that underscores every thread of every plotline – even if, with some, it’s only obvious in hindsight.

Ehuani is a central tenet of the Zeeranim, and maybe because the book opens in the Zeera desert, and the Zeeranim remain more-or-less the main characters of the story, it’s impossible for the reader not to take it in. The Zeeranim, this warrior-culture, are dying out – slowly, but it’s impossible to miss; the Sundering’s effects are perhaps nowhere more visible than in the Zeera. And out of this has grown this concept of ehuani, this unflinching facing of the truth, even when it’s uncomfortable or dangerous. I don’t remember any point where one of the Zeeranim lie by anything but omission, or tell any small white lies. There’s beauty in truth, even when the truth is ugly.

In many ways the Zeeranim are a ‘barbarian’ culture – they don’t live in houses, they don’t have kings and queens and palaces. They’re open in their violence and their hungers, their loves and their hatreds. (Mostly). And that means they clash hard with the Aturans, who are a more ‘typical’ fantasy people, one with castles and kings and cities – a people who are more familiar, more within the frame of understanding of at least this reader. But it’s not just the Zeera that’s dying; the Aturans may wrap the rotting limb in silks and satins, but it’s still rotting. They live – and lie – as though their kingdom will survive forever; the Zeeranim stare the future in the face and dare it to ‘show me yours!’

And that conflict – between harsh truth and willful blindness, between bluntness and suave lies, between wildness and luxury – is one that’s at the heart of this book in just about every way.

It’s terribly beautiful, and beautifully terrible. The descriptions are so lush, the writing practically decadent, even when the focus is the harsh and unforgiving Zeera desert. There are layers within layers within layers, stories that started before the book opens and weave their way through the main plotline; secrets and mysteries and magics that make your breath catch in your throat with both wonder and terror. Golden ram horns with death in their music; spider-mages; the realm of dreams, which is as beautiful as it is deadly, revealing awful and powerful truths via metaphor. There’s a dragon in the sky and another sleeping within the earth, and they’ll destroy the world if they ever come together. There are mages with diamonds set into their skins, bone flutes that make shadows dance, the king is slowly dying and the emperor is growing his army of half-fae warriors. (Fae isn’t the right word, but it’s the closest I can come without using words those who haven’t read the book won’t know). There are pearls and blades and blood, horses like silk and wind, masks upon masks upon masks. The mirrors here are blind; you have to look beyond them.

But honestly, the biggest, most important thing I can tell you is how this book made me feel.

Dragon’s Legacy feels like it was written just for me. And that’s strange for a few reasons; there’s no queer content, which is usually a prerequisite for me; it’s also arguably grimdark, which is a sub-genre I tend to steer well clear from. But this doesn’t feel grim to me, even when terrible things are happening. It’s raw and it’s real and it’s beautiful, it’s different, it’s a breath of fresh air from a world as real as our own. Is it a better world? No, I don’t think so. But it’s one with more wonder in it. It’s one that makes my heart sing and pound and dance. This isn’t a book you read; it’s one you fall into, plummet into, a book that swallows you up and makes you live it.

Run alongside the vash’ai with their voices in your mind. Hear the song of the Zeera as it howls across the sands. Salute Akari Sun-Dragon as he plunges over the edge of the horizon. Bare your teeth at the Nightmare Man, the shadows, the gilded lies. Watch the world slowly dying, and refuse to lie down and die with it.

That’s what Dragon’s Legacy captures, I think – that glorious, life-blazing defiance, the refusal to lie down and die, to give up, to not embrace everything life has to offer. It’s about fighting to survive because fuck any other option. It’s about shaping yourself into something greater, not just because that’s what’s necessary to survive, but because you are great, and you will make the world acknowledge that. And it’s about different kinds of greatness, strength, power; temporal, personality/charisma, physical, magical, will, and the ways in which they can intertwine and overcome each other. The ways in which one can grow into another. The evolution from insignificance to eminence.

This is a book – a series – that has flown so far under the radar it’s impossible to comprehend. Tor.com and Locus both forgot to include the final book of this trilogy when it was released this year, in their lists of new fantasy releases. I’ve run into no one else who knows this series, and I cannot understand why. This is a masterwork, a distillation of so many of the things that makes Fantasy, capital F, the best genre of all. When I included it in my Best of the Decade list last year, I said I’ve never read anything like it, and I doubt I ever will again, and I never, ever want it to end.

Every word of that is still true.

Ehuani.

The post There is beauty in truth: The Dragon’s Legacy by Deborah A. Wolf appeared first on Every Book a Doorway.

May 9, 2020

(Some of) The Coolest Magical Abilities in Fiction!

Last post, I talked about some of my favourite magic systems; this time around, I want to showcase some of my favourite magical/supernatural abilities. The difference? A magic system is a magic system; a magical ability is more like a superpower. The latter is a lot more limited in scope; a character with a magical ability can do one thing, rather than casting spells that could potentially do just about anything.

I guess it’s a fairly thin line separating the two, but that line’s enough to justify two separate posts, and that’s all I need!

(Although now I wish I’d saved the Water Giver trilogy for this post, where it probably fits a little better. Oh well!)

Introduced in Maggie Stiefvater’s Raven Cycle and featured in the sequel Dreamer trilogy are Dreamers – people who can take things out of their dreams and bring them into the real world. As you might imagine, some of those things are incredibly strange – some beautiful, some terrible, some both – but without question, it makes for one of the most incredible, and potentially dangerous, abilities on this list. After all, would you want to manifest your nightmares?

A secondary character who spends almost no time on the page, and yet is central to the second book of KD Edward’s Tarot Sequence, is Layne – a teenage necromancer. This isn’t your typical necromancy, though; Layne isn’t messing about with corpses or raising the dead, and though he* does draw power from death, he’s not sacrificing babies or neighbourhood cats. His form of necromancy is more properly called immolation magic – practitioners keep themselves infected with different illnesses, and when they need power, they kill the bacteria and harvest power from the deaths of those illnesses. It’s a really unique and clever twist on necromancy, and I for one absolutely adore it!

*Layne is referred to using he/him in Hanged Man, but it’s been revealed that Layne’s pronouns going forward in the series will be they/them.

Orogeny is an ability some people in Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy are blessed – or cursed – with; the power to sense, manipulate, and trigger energy – especially or primarily seismic energy. Because individuals who can create earthquakes even as infants are obviously very dangerous individuals, most people hate them; orogenes are victims of terrible prejudice and abuse, with people even suspected of having orogeny being beaten to death, especially in more rural areas. Whereas the Fulcrum, a kind of government body, raises, trains, and even breeds orogenes – because of course, although they might be dangerous, orogenes are also incredibly useful, especially in the world of the Stillness, where climatic cataclysms are a constant threat.

The full scope of orogeny is explored in fantastic detail over the course of the trilogy, and I don’t want to ruin it for new readers by going into spoiler territory. So I’ll just say that it’s ridiculously cool, and very definitely one of my favourite superpowers!

Heart of the Circle is special not so much for the magical ability possessed by the main character – empathy – so much as how it’s utilised. Landsman delves into the potential uses of being able to not just read, but manipulate the emotions of others – and it’s pretty damn incredible. Empaths work in marketing and publishing to infuse images and stories with real emotion, walk on the outside of protest marches to keep a look-out for violence before it starts – and are absolutely terrifying in combat. At one point in the book, the main character (an empath himself) reminisces about his time in the military, and one particular training exercise – when twenty or so other magic-users complained of being outnumbered when pit against a single empath and seer. That’s how scary empaths are. It’s really cool to me, because usually empathy is presented as a soft, gentle superpower, and here in Heart of the Circle, it’s the complete opposite.

The cassandra sangue of the Others series are not-quite-human, but aren’t Others (supernatural creatures like animal shapeshifters, vampires, and elementals) either. Their in-between state is explored later in the Others series, when it’s speculated that they might have evolved as mediators between humans and others (a concept I absolutely adore), but their primary power is in their skin. When a blood prophet’s skin is cut, she (cassandra sangue are always female) sees visions. Between that and their naive, naturally sweet natures (a generalisation, but a valid one) they’re inevitably taken advantage of and misused by those who want to profit from their prophecies. The series starts when one blood prophet escapes the compound she was born and raised in, and she and the found-family that forms around her explore the full extent – and danger – of her ability, step by step and book by book. The ramifications are enormous, and make for really interesting reading.

The God Eaters is one of my favourite books of all time, and one so few people seem to have heard of. Happily, it was just featured on Tor.com in a post by TJ Klune just this past week. It’s an incredible queer fantasy, not least because of its fantastic characters. One of which is Kieran, a Native American with a magical gift I’ve never seen before (or since) – he can will people to die. It’s a power that wouldn’t work in the hands of a lesser writer – Kieran would either be too strong to be interesting (how much fun do you have with super-superpowered characters, who are never in danger and can brush off any obstacle?) or for hand-wavey reasons wouldn’t be using his gift when it might interfere with the plot. But Hajicek makes it work, and work brilliantly, and I love, love, love the secret behind the source of that power, when it’s eventually revealed. It’s a unique magical power utilised expertly by a master storyteller, and you absolutely need to check it out.

(You can grab an e-copy over at Lulu.com – no affiliate link, I just want everyone to be able to read this book!)

Margerit, a young woman who receives an unexpected inheritance that will alter the course of her life, is special even before she becomes an heiress – she can see magic.

Of course, that’s not what she, or anyone else calls it – in Jones’ regency setting, what I call magic is considered the manifestations of saints and angels, something that’s only lightly questioned later in the series by less religious characters. But the point remains that Margerit sees beautiful colours and glowing lights during rituals – and can use that sight to tell when a ritual has gone wrong. She even utilises her ability to build entirely new rituals, ones with real and powerful effects. It’s a wonderful power, and it’s just as wonderful to read about as Margerit goes from considering it a small and unimportant thing, to embracing her power and making it the focus of her life.

In Reverie, people’s dreams and fantasies keep manifesting into reality – sweeping up everyone nearby into the dreamer’s story. A rare few are immune, able to remember who they are even when caught in someone else’s ‘reverie’ – said dreams – and who can help the plot of the dream reach its conclusion without anyone getting hurt. This is made easier by the fact that everyone who can stay awake through a reverie seems to get superpowers – like super-strength – but it’s the staying-awake-and-aware ability that earns Reverie a spot on this list.

The reveries themselves are a really cool concept, as is the idea of people whose magic is being immune to magic – at least this one specific kind of magic, anyway!

The clue’s in the name: inklings, as they’re known, are people who can manipulate holy ink. The most common way they do this is by drawing on themselves – or someone else – and making the message or picture transfer from their skin to someone else’s. The church ’employs’ (a better word might be ‘enslaves’) inklings to pass on divine messages to parishioners – the inkling considers the message, draws an image that embodies that message, and then sends it from their own skin to the intended recipient, who will bear it as a permanent tattoo for the rest of their lives.

The main characters, Celia and Anya, find a new way to utilise their power – one that gives them a way out of the church’s oppression and a way in to a new and brilliant new life. I’m not going to tell you what it is, because spoilers, but it’s fabulously clever. And the inklings’ power definitely counts as a unique one!

So those are some of my faves – what about yours? What are some of the coolest magical abilities you’ve read about? And what power, if you could pick, would you choose for yourself?

The post (Some of) The Coolest Magical Abilities in Fiction! appeared first on Every Book a Doorway.

May 5, 2020

Ten Ridiculously Cool Magic Systems!

phoenix art credit Sujono Sujono

For my third Wyrd & Wonder entry, I wanted to showcase some of the coolest magic systems I’ve come across!

Magic systems tend to be divided into roughly two camps: Hard and Soft. Hard systems are almost scientific in their rules and how they work; a good example is the one in Patrick Rothfuss’ Kingkiller Chronicles, where the magic taught at ‘wizard university’ has very strict rules indeed. Even the magic in Paolini’s Inheritance Cycle, though superficially Very Mysterious, is determined by grammar and by energy cost.

Soft magic systems, on the other hand, are what I consider Real Magic – mysterious, hard to pin down, inexplicable in a way that evokes wonder. Soft magic feels actually magical, whereas Hard magic is just…science.

Not that science can’t be awe-inspiring. Hm. Maybe it would be better to say that it’s like science the way it’s taught in high school – magic with all the magic stripped out of it.

…I might be a tiny bit biased in my analysis. Tiny bit.

A critical difference between the two, by the way, is how much of the system gets explained to the audience. The magic in Unnatural Magic by [author] is reminiscent of math or computer code – we know there are rules. But because those rules of it aren’t all laid out for the reader, the magic doesn’t have the feeling of a stage magician’s trick explained. It stays marvelous.

Anyway! So here are some of my faves, and no surprise, they’re all Soft systems!

In Merciful Crow (and presumably the rest of the ____ trilogy, though the other books haven’t been released quite yet) everyone has some little bit of magic, but ‘proper’, impressive magic is the domain of witches – which doesn’t sound so odd, until you learn that the number of witches born into each of society’s castes is determined by how many gods that caste had, back before all the gods died. The higher the caste, the fewer gods they had, which has the interesting knock-on effect of meaning that the lower and more down-trodden castes have far more witches than the nobles and royalty.

Every caste – all of which are named after birds – has its own gift, and every member of that caste can use the gift to some degree. But witches, while having the same gift, pack a much, much bigger punch than the rest of the population.

The Crow caste – considered the lowest of the low – has the magic that earns this book a spot on my list: Crow witches can use the gifts of any other caste – if they have the teeth of someone who belonged to that caste. It’s pretty incredible, and adds a very interesting element to the already complicated interactions between Crows and the rest of the kingdom. Plus, it makes for very bad-ass fashion accessories: the chiefs of the travelling Crow flocks wear necklaces made up of the teeth of non-Crows, so they can use any caste-gift as it’s needed.

Another series whose magic system revolves around teeth, the Daughter of Smoke and Bone trilogy is difficult to talk about without giving away spoilers – the full impact and power of the tooth-magic is revealed later in book one, and it’s a pretty big plot point. But the info the reader starts with is that teeth = wishes. Sounds great, right? Well, kinda. The problem is, a single tooth = a very small wish – enough to change the colour of your hair, say, but not much more. And you can’t add a bunch of teeth – or little wishes – together to make a big wish. To get a big wish, you need all the teeth from a person’s mouth – and to get the biggest wish, you need to give all of your own teeth.

That’s already a really cool magic system, but as hinted, the power of the teeth is even greater than the ability to grant wishes…

The Lightbringer series by Brent Weeks features a society built around the magic of colour – and I mean that literally. Drafters are people able to ‘draft’ colour from light – take it into themselves, and then manifest it in a physical form. It’s especially cool because each colour has different properties in its physical form – green is elastic, perfect yellow is unbreakable, etc – as well as manifesting emotionally within the drafter: red ’causes’ passion, blue compels rational thinking, and so on. Drafting also has permanent effects on drafters; the more a person drafts, the more their eyes are stained with whichever colour or colours they draft (few people can draft two colours, three is incredibly rare, and to be able to draft more than that is almost unheard of). When the colour/s eventually overflows the iris, aka ‘breaking the halo’, the drafter goes mad and has to be put down.

Everything in the Seven Satrapies revolves around colour and drafting, from agriculture to fashion to religion. Magic is a vital part of the economy and every aspect of life, and almost as amazing as the system itself is how well-thought-out the ramifications of it are on Weeks’ world.

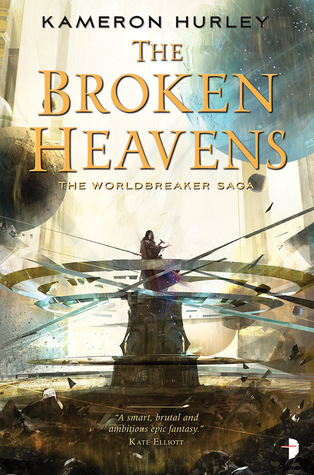

In the Worldbreaker saga, jistas are mages who draw power from one of the four satellites – Para, Tira, Sina, or Oma. ‘Satellites’ is used here in the astrological sense; Oma and the rest are some kind of strange stars/astrological bodies with unpredictable orbits; although the astrologists can estimate when one will appear in the sky and one will disappear, they’re only ever estimations. Each of them cast a different coloured light; Oma’s light is red, Para’s is blue, and so on. Jistas can only draw from a single satellite, and only when their satellite is in ascendance – Para might hang around for a few decades, giving parajistas plenty of power, before vanishing as Tira replaces it – causing the parajistas to lose their magic, and the tirajistas to regain theirs. Each satellite bestows different slightly different abilities – Tira is particularly good for healing – and jistas must learn special litanies in order to channel the power of their satellite.

The trilogy’s plotline revolves around the rise of Oma, which is known to bring chaos and destruction whenever it appears in the skies. Luckily, it doesn’t appear very often – about every two thousand years – but it’s even less predictable in its appearances and disappearances than the other satellites, making it difficult to prepare for its coming. Omajistas are therefore the rarest of jistas – but also, arguably, the most powerful, with one power in particular that is absolutely priceless to the different worlds that clash over the course of the saga.

The law is magic – or is magic the law? – in Three Parts Dead, the first in the Craft Sequence. Drawing power from starlight and trained in an invisible academy in the sky, Craftspeople are very like lawyers in Gladstone’s universe – they negotiate contracts, file lawsuits, and defend and prosecute defendants in trials.

It’s just that those contracts are between gods, the lawsuits regard stolen soul-stuff, and depositions and presenting evidence in trials takes the form of magical battles with opposing counsel.

The Craft isn’t the only form of magic in the series, but it is the only one (if I remember correctly) which is entirely created, fuelled, and practised by humans – other magic systems have humans drawing power from gods they’ve made compacts with or oaths to. It gives the Craft an interesting place in the structure of its world, because the Craft is symbolic of humanity’s independence from the gods – something which is a major theme underlying the whole series.

‘Life is magic’ is the mantra that repeats again and again in Kate Griffin’s Matthew Swift series. These books are the quintessential urban fantasy, with magic literally created out of/pulled from the urbane – golems built out of trash, sigils painted in graffiti, prophecies writ in the patterns of plastic bags blown in the wind, and rituals wrought out of the patterns of rush-hour. The moment I knew this series was something special was scene, early in the first book, when the eponymous Matthew Swift crafts a protection spell by swiping his travel card and standing on one side of the turnstile – turning the terms and conditions on his card into a protection spell from the monster stuck on the other side. Griffin does that over and over, taking the mundane and turning it into magic, from night buses to pigeons to phone lines to the Dragon of London, and it’s a ridiculously incredible thing to watch. Nobody does urban fantasy like the Matthew Swift series, because only these books literally build fantasy out of the urban.

Another series where life and magic are inextricably intertwined, the Towers trilogy is set in a post-apocalyptic world where, somehow, everyone has magic. Just a little bit, enough to press into coins and use as currency – unless you’re one of the rich and privileged, living in towers floating above the city of ruins below. The towers are powered by the magic – the life force – of their inhabitants, and it makes them luxurious havens, a completely different world to that of the people living on the ground.

The trilogy plays with the ideas of life and death as magical forces – Xhea, the main character, is a freak oddity, the only person anyone’s ever heard of with no magic at all; whereas Shai is a Radiant, someone born with too much magic – which means too much life. That manifests in the form of horrific cancers, produced by that excess life-energy – life-energy that is still present even when Shai is a ghost. Like I said, plenty of interplay between life and death, and where the line between them lies, and when something or someone moves between one and the other. Really cool, and the way it’s utilised in Sumner-Smith’s world is just brilliant.

In the Creature Court series, power comes from the sky – as do terrible monsters that attack the cities below every night. But the cities have protectors – Courts made up of men and women who have been touched by animor, a strange and feral energy that turns them into cubs, Lords and Kings, giving them the power to fight the sky. The more animor a person has, the more powerful they are – grow powerful enough, and you become a King. Grow stronger than the other Kings in the court, and you become Power and Majesty, the King of Kings. Animor is a mysterious thing; it’s unclear where it comes from or even how it works, but those who wield it become more feral than ‘normal’ people, even turning into animals when they battle. (One detail I love is that almost no one turns into one animal – the transformation is affected by body weight, so the character who turns into cats turns into many cats at once, since a human’s body weight = at least a dozen cats, right?) Animor also creates prophets and guardians, who have their own abilities but can’t transform or fight the sky directly.

The secrets of animor do come out eventually, by the end of the trilogy…and damn, it’s one incredible ride. Even without the really cool magic system, this is one of my favourite trilogies of all time!

The Watergivers trilogy is set in a desert land, where all life depends on the stormlords – magic-users who can gather clouds and summon rain. They come in levels of strength – stormlords, and the lesser rainlords, who can’t create storms of their own but can still manipulate water. In the desert setting, water is everything – currency, religion, and an obviously vital resource; one of a rainlord’s responsibilities is drawing the water from dead bodies to make sure not one drop is wasted. Besides being an amazing story, the trilogy plays with this unique magic system in all sorts of ways – I’m always trying to push these books into people’s hands!

In the world of the Long Price quartet, magic is – kind of – poetry. In fact, mages are given the title of Poets once they graduate from a very intense schooling – and the magic they perform? Consists of taking concepts and manifesting them into living, sentient forms, which the Poets then control totally. The manifestation is done by defining the concept, which is difficult enough – but since entire economies grow up around the concepts so embodied, successor Poets have to try and take hold of that concept so it doesn’t disappear when the first Poet dies. And that’s a problem, because the concept will ‘escape’, or not manifest, if the definition written is too close to a definition that was written before.

If that sounds complicated, it is, but though it’s an integral part of the quartet, the reader doesn’t need to be too concerned with the intricate details (alas – I would have found them pretty cool). Book one revolves around the concept nicknamed Seedless, which has turned the kingdom it exists in into a major exporter of fabrics – since it removes the seeds from cotton, making harvesting and spinning it much, much easier and faster.

The thing is, Seedless – and all the other concepts – hate the Poets and don’t want to be material, living beings at all. The Poets have to fight to hold them, and the concepts do all they can to escape. The series follows the give-and-take between various Poets and the concepts they hold captive, and the fall-out when those conflicts spill over to the rest of humanity.

So! Those are some of my favourite magic systems. Tell me about some of yours!

The post Ten Ridiculously Cool Magic Systems! appeared first on Every Book a Doorway.

May 3, 2020

Fantastic Beasts, Here You’ll Find Them: Unicorns!

phoenix art credit Sujono Sujono

For my second Wyrd & Wonder post, I wanted to feature my favourite magical creature of all time – the unicorn!

Listen, I love unicorns, and I make absolutely no apologies for it. I don’t remember when I fell in love with them, but since I don’t remember a time in my life when I wasn’t… It’s safe to say they stole my heart quite a while ago.

art by inkscribble

art by inkscribbleNor am I the least bit subtle about it: my rucksack is covered in unicorns, my purse has a unicorn on it, my keys are guarded by unicorn keyrings, and there are days I’m dressed in unicorns from my earrings to my socks. My bestie bought me a unicorn hoodie for Yule. When I say I love unicorns, I mean I LOVE unicorns.

I love them when they’re sparkly, and I love them when they’re glorious, dangerous creatures. I love that they embody both wildness and femininity, two concepts that should go together more often. It tickles me that black unicorns apparently symbolise sodomy (although I only ever found one source for that, and nothing to corroborate it.) I don’t see unicorns as tied to Christianity, or virginity, but I do see them as hopepunk icons.

…Gotta write an essay about that sometime. *scribbles*

The Dark Unicorn Giclee on German Etching by artist Michael Parkes

The Dark Unicorn Giclee on German Etching by artist Michael ParkesIt therefore saddens me greatly that it’s so hard to find really good unicorn stories. Most are written for much younger readers; unicorns might appear in passing in adult fantasies (such as in Miles Cameron’s Masters & Mages trilogy, where the General rides a unicorn into battle), but they rarely feature. This, then, is my attempt to gather a few of the best ones into a single list, in the hopes that it reaches some other unicorn-lovers out there.

(And no, The Last Unicorn doesn’t make the cut. I’m not a fan, although I have no issues with anyone who is. It just didn’t quite click for me!)

The Firebringer trilogy series is best summed up as: Watership Down, but unicorns. What at first seems like a very simplistic story for children rapidly reveals itself to be much more complex, and unafraid of tackling difficult questions; although written for a younger audience, I think it has something to offer adults as well.

Jan is the prince of the unicorns, who are in turn the chosen people of the goddess Alma: raised up above the animalistic pans (fauns) and the monstrous gryphons. But Jan is hardly the perfect prince; he’s reckless, a rule-breaker, impatient to be allowed to go through the adulthood rite of his people and be allowed to join the herd’s warriors. His father, Korr, is an imperious and powerful figure, one that’s hard to live up to – but when he finally allows Jan to make the journey to their people’s sacred pool, it sets Jan on a journey prophesied a long, long time ago.

Over the course of the books, Jan discovers that the history he’s been told is full of holes or outright lies; that the prejudices the unicorns hold for other creatures are baseless; that there are other ways to live than the way he does. Racial stereotypes, the unhealthy weight of tradition, the value of peace over war, standing up for what’s right; these are just some of the issues the trilogy examines. And, frankly, the unicorns and their culture are just fantastic.

Ariel is set in the aftermath of the end of the world; when technology died without warning, magic came back, and 99% of the human population vanished without explanation. Pete, who’s a teen when the Change occurs, survives alone as a scavenger – until he meets a unicorn he names Ariel. With his help, Ariel learns to speak and read, and eventually the two of them stand as equal companions. Pete is the narrator of the book, but Ariel is a major character, sharp and funny and beside Pete every step of the way on their journey to confront the sorcerer who wants Ariel’s horn.

The Obsidian Trilogy is kind of the epitome of classic fantasy – we have humans, elves, and demons (as well as sundry other ‘wild-folk’ like centaurs and undines), and, as you can see from the covers, dragons – and unicorns. Kellen is the son of the Arch-Mage, living in the Golden City of Bells – a city ruled over by the Council of Mages. Within the City, everything is perfect…and never-changing; there are rules about everything, down to the smallest of minutiae, and the rules must never be broken. So when Kellen discovers Wild Magic, anathema to the hidebound Mages, and refuses to give it up, it gets him exiled.

Shalkan, a talking unicorn, becomes his rescuer and companion in Kellen’s journey beyond the City. It’s a long journey, with a destination he could never have imagined – the Obsidian Mountain, home of demonkind…

There’s a lot of cool things about this trilogy, not least the unicorns themselves – these are non-equine unicorns, and can only be approached and touched by virgins. The touch of a unicorn’s horn is instant and total death to demons, which makes the unicorn-mounted elven warriors a vital force. Lackey and Mallory don’t really suborn the classic tropes much – the demons are very demon-y – but the worldbuilding around the elves is pretty fabulous, especially their obsession with tea!

The sequel trilogy set in the same universe a century (or more?) later, also features a unicorn companion to the human adventurers.

One of my favourite series of all time, the Black Jewels series – especially the core trilogy made up of Daughter of the Blood, Heir to the Shadows, and Queen of the Darkness – doesn’t give unicorns a major part, but they are incredibly beautiful, magical creatures with a very special part to play. In the world of the Black Jewels, unicorns are Kindred – sentient, sapient creatures kin to the magic-using Blood of the human races. And when Witch, who is Dreams Made Flesh – the dreams of every race, longing for the perfect Queen – arrives to walk the realms, she embodies the dreams of the unicorns too.

(A head’s up that book one, Daughter of the Blood, has some really dark content in it, so please look up the content warnings if you know you have triggers!)

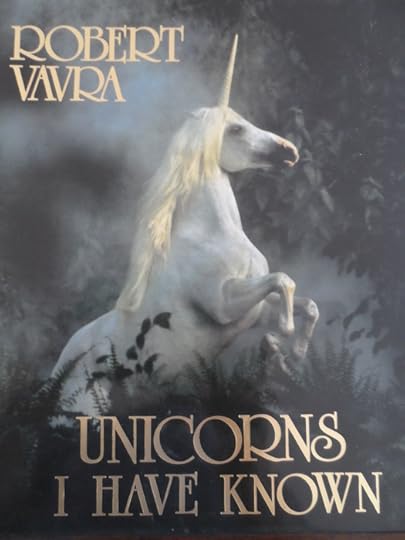

Unicorns I Have Known is not a novel, but a collection of ‘unicorn’ photographs accompanied by notes on unicorn sub-species and behaviour – a kind of naturalist’s travelogue. The photographs are gorgeous, but it’s the sketches and unicorn-ology in the calligraphic notes that made this book really special to me, and a must-have for any unicorn lover – if you can track down a copy!

The Unicornis Manscripts is another non-novel, a book whose conceit is that it contains the translations of an ancient manuscript about unicorns, their abilities, history, and behaviour. It’s an incredible work of art, full of sketches and drawings reminiscent of Michelangelo’s, with original lore and a lovely memoir-esque feel as Green describes his journey with the eponymous manuscripts. Again, it’s a priceless treasure for anyone who loves unicorns.

Feel free to drop recs in the comments – I’m always looking for more unicorn books!

The post Fantastic Beasts, Here You’ll Find Them: Unicorns! appeared first on Every Book a Doorway.

Fantastical Beasts, Here You’ll Find Them: Unicorns!

phoenix art credit Sujono Sujono

For my second Wyrd & Wonder post, I wanted to feature my favourite magical creature of all time – the unicorn!

Listen, I love unicorns, and I make absolutely no apologies for it. I don’t remember when I fell in love with them, but since I don’t remember a time in my life when I wasn’t… It’s safe to say they stole my heart quite a while ago.

art by inkscribble

art by inkscribbleNor am I the least bit subtle about it: my rucksack is covered in unicorns, my purse has a unicorn on it, my keys are guarded by unicorn keyrings, and there are days I’m dressed in unicorns from my earrings to my socks. My bestie bought me a unicorn hoodie for Yule. When I say I love unicorns, I mean I LOVE unicorns.

I love them when they’re sparkly, and I love them when they’re glorious, dangerous creatures. I love that they embody both wildness and femininity, two concepts that should go together more often. It tickles me that black unicorns apparently symbolise sodomy (although I only ever found one source for that, and nothing to corroborate it.) I don’t see unicorns as tied to Christianity, or virginity, but I do see them as hopepunk icons.

…Gotta write an essay about that sometime. *scribbles*

The Dark Unicorn Giclee on German Etching by artist Michael Parkes

The Dark Unicorn Giclee on German Etching by artist Michael ParkesIt therefore saddens me greatly that it’s so hard to find really good unicorn stories. Most are written for much younger readers; unicorns might appear in passing in adult fantasies (such as in Miles Cameron’s Masters & Mages trilogy, where the General rides a unicorn into battle), but they rarely feature. This, then, is my attempt to gather a few of the best ones into a single list, in the hopes that it reaches some other unicorn-lovers out there.

(And no, The Last Unicorn doesn’t make the cut. I’m not a fan, although I have no issues with anyone who is. It just didn’t quite click for me!)

The Firebringer trilogy series is best summed up as: Watership Down, but unicorns. What at first seems like a very simplistic story for children rapidly reveals itself to be much more complex, and unafraid of tackling difficult questions; although written for a younger audience, I think it has something to offer adults as well.

Jan is the prince of the unicorns, who are in turn the chosen people of the goddess Alma: raised up above the animalistic pans (fauns) and the monstrous gryphons. But Jan is hardly the perfect prince; he’s reckless, a rule-breaker, impatient to be allowed to go through the adulthood rite of his people and be allowed to join the herd’s warriors. His father, Korr, is an imperious and powerful figure, one that’s hard to live up to – but when he finally allows Jan to make the journey to their people’s sacred pool, it sets Jan on a journey prophesied a long, long time ago.

Over the course of the books, Jan discovers that the history he’s been told is full of holes or outright lies; that the prejudices the unicorns hold for other creatures are baseless; that there are other ways to live than the way he does. Racial stereotypes, the unhealthy weight of tradition, the value of peace over war, standing up for what’s right; these are just some of the issues the trilogy examines. And, frankly, the unicorns and their culture are just fantastic.

Ariel is set in the aftermath of the end of the world; when technology died without warning, magic came back, and 99% of the human population vanished without explanation. Pete, who’s a teen when the Change occurs, survives alone as a scavenger – until he meets a unicorn he names Ariel. With his help, Ariel learns to speak and read, and eventually the two of them stand as equal companions. Pete is the narrator of the book, but Ariel is a major character, sharp and funny and beside Pete every step of the way on their journey to confront the sorcerer who wants Ariel’s horn.

The Obsidian Trilogy is kind of the epitome of classic fantasy – we have humans, elves, and demons (as well as sundry other ‘wild-folk’ like centaurs and undines), and, as you can see from the covers, dragons – and unicorns. Kellen is the son of the Arch-Mage, living in the Golden City of Bells – a city ruled over by the Council of Mages. Within the City, everything is perfect…and never-changing; there are rules about everything, down to the smallest of minutiae, and the rules must never be broken. So when Kellen discovers Wild Magic, anathema to the hidebound Mages, and refuses to give it up, it gets him exiled.

Shalkan, a talking unicorn, becomes his rescuer and companion in Kellen’s journey beyond the City. It’s a long journey, with a destination he could never have imagined – the Obsidian Mountain, home of demonkind…

There’s a lot of cool things about this trilogy, not least the unicorns themselves – these are non-equine unicorns, and can only be approached and touched by virgins. The touch of a unicorn’s horn is instant and total death to demons, which makes the unicorn-mounted elven warriors a vital force. Lackey and Mallory don’t really suborn the classic tropes much – the demons are very demon-y – but the worldbuilding around the elves is pretty fabulous, especially their obsession with tea!

The sequel trilogy set in the same universe a century (or more?) later, also features a unicorn companion to the human adventurers.

One of my favourite series of all time, the Black Jewels series – especially the core trilogy made up of Daughter of the Blood, Heir to the Shadows, and Queen of the Darkness – doesn’t give unicorns a major part, but they are incredibly beautiful, magical creatures with a very special part to play. In the world of the Black Jewels, unicorns are Kindred – sentient, sapient creatures kin to the magic-using Blood of the human races. And when Witch, who is Dreams Made Flesh – the dreams of every race, longing for the perfect Queen – arrives to walk the realms, she embodies the dreams of the unicorns too.

(A head’s up that book one, Daughter of the Blood, has some really dark content in it, so please look up the content warnings if you know you have triggers!)

Unicorns I Have Known is not a novel, but a collection of ‘unicorn’ photographs accompanied by notes on unicorn sub-species and behaviour – a kind of naturalist’s travelogue. The photographs are gorgeous, but it’s the sketches and unicorn-ology in the calligraphic notes that made this book really special to me, and a must-have for any unicorn lover – if you can track down a copy!

The Unicornis Manscripts is another non-novel, a book whose conceit is that it contains the translations of an ancient manuscript about unicorns, their abilities, history, and behaviour. It’s an incredible work of art, full of sketches and drawings reminiscent of Michelangelo’s, with original lore and a lovely memoir-esque feel as Green describes his journey with the eponymous manuscripts. Again, it’s a priceless treasure for anyone who loves unicorns.

Feel free to drop recs in the comments – I’m always looking for more unicorn books!

The post Fantastical Beasts, Here You’ll Find Them: Unicorns! appeared first on Every Book a Doorway.

May 1, 2020

Why Fantasy? Because It Saved Me

phoenix art credit Sujono Sujono

I couldn’t think of a better way to start Wyrd & Wonder than explaining why Fantasy is the best the genre that means the most to me. It’s defined my life and shaped who I am as a person (and I’m very, very happy about that). But head’s up, there’s some rough content in this story, so please pay heed to the content warnings.

Trigger warnings: mentions/discussions of spousal abuse, child abuse, and mental illness

There’s this thing I’ve heard – that many Fantasy fans have probably heard at one point or another: ‘Scifi looks forward; Fantasy looks backwards.’

It’s said patronisingly, contemptuously, dismissively; it’s presented as inarguable evidence that Fantasy is somehow lesser. And I could probably have a ton of fun digging into that – I could write an essay about how the concept of magic has been inextricably tied to women in the European and North-American tradition, how the dismissal of Fantasy is, at its core, all tied up with the same misogyny that causes people (even many fantasy fans!) to show the same contempt for the romance genre. Magic = witchcraft = the witch trials, which in their turn were hugely motivated by the male medical profession wanting to get rid of the primarily female traditions of midwives and herbwomen.

Medicine was only acceptable when practised by men. And Fantasy has kind of had the same problem for a while – we’re constantly hearing that women don’t write it at all, or if they do, it’s romantic Fantasy (which doesn’t count, remember). Good Fantasy, respectable Fantasy, is written by men. Straight white cis men, specifically. One such, Terry Pratchett, hit the nail on the head when describing the differences between the cultural views on wizards and witches;

Sorceress? Just a better class of witch. Enchantress? Just a witch with good legs. The fantasy world, in fact, is overdue for a visit from the Equal Opportunities people because, in the fantasy world, magic done by women is usually of poor quality, third-rate, negative stuff, while the wizards are usually cerebral, clever, powerful, and wise.

Strangely enough, that’s also the case in this world. You don’t have to believe in magic to notice that.

Wizards get to do a better class of magic, while witches give you warts.

Terry Pratchett, Why Gandalf Never Married

It’s good reading, Why Gandalf Never Married. I recommend checking it out if you haven’t already.

And this is all without bringing genderqueerness into it. Gods forbid.

It’s not just about deeply ingrained misogyny, though, I don’t think. Magic and the magical are also inherently other, and humans, as a group, don’t tend to like things that are other very much. And then there’s the weird thing about how Fantasy is somehow childish, that a person is somehow weak or pathetic or naive for clinging to it past a certain age. There’s a point in our lives when we’re expected to lay down the magic wands and 20-sided dice and grow up. And growing up, in this context, means (as far as I’ve ever been able to tell) acknowledging that the world is a grim and gritty place where things aren’t fair and wishes don’t come true. It’s the black-and-white Kansas that is reality, not the technicolor Oz, after all. The real world doesn’t have colour.

I think this is why there’s some kind of odd prestige attached to ‘grimdark’ Fantasy. After all, that’s ‘realistic’ Fantasy. It’s Fantasy set in a world that’s as horrible as our own, right? Except… Our world isn’t nearly as fucking bleak as proponents of grimdark, or of growing up, seem to want us to believe. Yes, there’s plenty of horrific things going on in the world every day, but there’s also so much hope and beauty and wonder. To claim there isn’t is just as naive, and maybe even more damaging, than refusing to acknowledge the messed-up stuff.

Anyway. That’s not the essay I wanted to write. Maybe another time.

*

‘Scifi looks forwards; Fantasy looks backwards.’

I’ll get back to that.

*

It doesn’t take a genius to work out why I was drawn to Fantasy. I can psychoanalyse myself just fine. It was escapism, pure and simple: my mother had bipolar disorder, and she was (as very few bipolar people are) physically violent. She put my father in hospital on multiple occasions (since she was all of four-feet-five and he was six-three and an ex-rugby player, no one, from the hospital staff to the courts, ever believed him). She once tried to run him over while my siblings and I were in the car. And although she never went after my brother and sister, she was physically abusive towards me from the time I was six, episodes that ranged from dragging me up the stairs by my hair to beating me black and blue with a wooden spoon.

Someday I’ll go back to Ireland, where most of this went down, and track down the court records of the nine custody battles my parents went through. Someday I’ll get the names of the judges who kept awarding custody to my mother, and I’ll call them up and ask what the fuck.

Regardless, it makes it almost embarrassingly easy to see why I fell into Fantasy. Pure escapism, right?

Well, no. I think anyone who sums Fantasy up as escapism is oversimplifying it. There’s nothing wrong with escapism, but escapism isn’t unique to Fantasy – any genre can be escapist; it depends on the tastes of the audience. Some people read historical fiction for escapism; some people read romance. So if escapism is all you want – all baby!Sia wanted – well. I could have gone in any direction. It didn’t need to be Fantasy.

In fact, it wasn’t at first. I remember reading a lot of Jacqueline Wilson books when I was little – Tracy Beaker, The Illustrated Mum, The Bed and Breakfast Star, all featuring heroines in situations with painful similarities to mine. Then there was Anne Fine’s Charm School, where a tomboy unlearns her hatred for femininity while teaching a bunch of ‘girly-girls’ that it’s okay to be feminine and interested in science, or sports, or special effects – a priceless book for a little girl* whose mother despised her for not being the little princess she’d dreamed of having while pregnant.

*I’m not a girl; I’m agender, she/her pronouns. But baby!Sia thought she was a girl.

Those books might not have been escapist, but they were stories about girls very like baby!Sia, with blueprints for how to try and survive. So why the shift to Fantasy?

The truth is, I don’t know. One of my earliest memories is my sixth birthday party, which was unicorn-themed from top to bottom: all of us in unicorn costumes, a unicorn birthday cake, a unicorn-shaped piñata. So clearly, I already belonged to Fantasy then, long before I remember starting to choose stories full of magic to read. I already loved my mermaid dolls and made up games where my friends and I pretended to be vampires or dragons or magical rabbits.

And I didn’t grow out of it.

In fairness, I don’t remember anyone trying to make me: both my parents were happy to see me reading, and I got books even when I didn’t get food. But I can trace a path through my childhood, a shift as I started to read more and more and play outside less. We moved houses every year, and I flashed in and out of different schools too fast to make proper friends. That explains the bookishness, surely – books were friends I could carry with me wherever we moved, worlds I could disappear into when I had to hide from my mother in the garage or behind curtains, dependable comforts when said mother was finally hospitalised and the real world turned upside-down and shook hard.

But why Fantasy?

Because nothing was fixed at the end of The Illustrated Mum. Because Charm School told me it was okay to be myself, but it couldn’t make my mother accept the same. Those books told me I could survive, but they had nothing to offer beyond that – and most of us want to do more than just survive. Even as children.

But Ella Enchanted said that I could be young and isolated and cursed, and still overcome it all by digging my heels in and being brave and smart; that I could have a sanctuary inside my head even when my body was stuck or surrounded by those who wanted to hurt me. Howl’s Moving Castle said I was special even if the people around me didn’t think so, that wicked witches were no match for being stubborn and smart. Spindle’s End said you could have a happy ending even if you didn’t want to be a princess, that it was more important to be good and brave. Northern Lights (also known as Golden Compass outside the UK) said that sometimes mothers were bad, and it had nothing to do with you; that sometimes adults couldn’t or wouldn’t save you, but you could save yourself.

Other stories insisted that the world was not a dark and terrible place, that there was so much more than fear and pain and confusion in it – and that those things could be overcome. Books like d’Lacey’s Fire Within and Funke’s Inkheart promised that there was magic in the real world, too, if you kept your eyes and heart open and believed. I was too young to understand that the Dragonology books were meant as fiction, and took them as proof that dragons were real, out there in the wide world (especially easy to believe since I’m half-Welsh, and everyone knows Wales is full of hidden dragons.) Spellhorn, Silver Crown, Artemis Fowl, Sabine, Roald Dahl’s Matilda, Jeremy Thatcher Dragon Hatcher, Rachel Roberts’ Avalon series (with the original, delightfully lurid covers) – all of them insisted that the real world had incredible, beautiful things in it. I just had to find them.

And if I couldn’t? Then I didn’t have to stay – Spellfall, Neverending Story, Gaiman’s Stardust, all promised that other, even more fantastical worlds were right alongside ours. I only had to find the right door, or a horse figurine from Stravaganza, to slip away completely.

(I had, and have, no patience for the Narnia books. They were too cruel, spitting the adventurers back into our world when they weren’t useful any more. I hated Aslan, as that perpetual ‘grown-up’ figure who pretends to be kind while leaving you out in the cold – and yes, I get the irony, seeing as he’s supposed to be a stand-in for Jesus, of all things.)

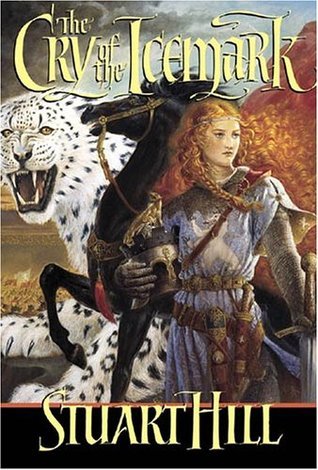

Fantasy gave me hope, in a way I wasn’t aware of at the time. I don’t like to think about how I might have turned out if I’d had no evidence that there was more than bitterness in the world. I do know I probably wouldn’t have survived if I hadn’t had Thirrin Freer Strong-in-the-Arm Lindenshield as a role model, as proof that a 14-year-old could stand against any enemy and win – something that played out very literally when I took my mother to court to force her to give up custody; I turned 14 during the subsequent legal battle. Cry of the Icemark, the book where Thirrin stars, is still very precious to me because of that, and probably always will be.

So…why Fantasy? Because my life was too tangled-up, too weird, and too unbelievable to be real. Over the years I’ve lost count of the number of people who’ve called me a liar when they hear my backstory, and I don’t blame any of them. The full story is beyond belief, so really, how could contemporary fiction hold my attention? How could I connect with it? Whereas Fantasy was full of kids with beautiful or bizarre backstories, facing trials and tribulations ‘normal’ people couldn’t possibly understand. Fantasy was full of ‘othered’ children who turned out to be special, powerful, indestructible.

For obvious reasons, I needed that.

As I got older, the books I read became more complicated. (The best children’s books don’t talk down to children, but there’s still a reason Middle-Grade fiction and Adult are two different sections of the bookshop.) The stories became more nuanced, the adventures scarier, the stakes and costs higher. But heroes stayed heroes. The villains were still defeated. It might take time, and blood, and real losses, but in the end, all would end well, every time.

A lot of Fantasy is a bit simplistic that way. That’s pure escapism; it’s not a good thing to absorb and try to apply to the real world, which is not so easily divided up into Good and Bad.

But.

There are exceptions, obviously. The whole sub-genre of grimdark, for one. But in general… The thing about Fantasy is that, the heroes, the leads – it’s not just that they defeat evil. It’s not even that they survive evil. It’s about how hard they fight to be good.

Being good is often hard. It’s often complicated. But to speak in sweeping generalities, Fantasy takes the best of humanity and puts it on the page (or the screen, or the gameboard, or any other medium of your choice). Is that ‘best’ often filtered by white, patriarchal, North American/West-European views of ‘goodness’? Definitely. Plenty of Fantasy stories take place within settings that utilise but don’t examine or challenge those same white-patriarchal-NA/WE frameworks, and that’s an issue all on its own. But for all its flaws, those stories still, at heart, revolve around characters that are good, or who are trying to be good.

I think that’s the heart of the genre. Or at least, the part that calls to me so strongly. Besides the sheer wonder and beauty of beings like dragons, and unicorns; besides the pure magic of magic; besides all the things that just make Fantasy so much better than reality. Besides all that.

The stories I read growing up were simplistic. A lot of Fantasy I’ve read as an adult are much more complicated, in the very best of ways, but again, speaking in generalities, Fantasy is about being good and defeating evil.

The real world’s not that simple. But that’s not the point. The point is that Fantasy tells us, shows us, proves to us that evil can be defeated. That heroes exist; that normal people can step up and become heroes. And those are the priceless lessons that Fantasy has to teach us. The lessons – morals, messages, whatever – that we need to internalise. That I needed, and still need, to internalise.

Internalise, and then project outwards.

Because that’s it. It’s not that Fantasy looks backwards. Fantasy looks inwards, sifting through the detritus inside all of us until it finds the best parts – and then it distils those best parts, crystallises them. Fantasy takes all of that and projects it outward again. It says that we can be good. It says the world can be good. It says, we must fight evil where we find it. It says, we can win.

(The best Fantasy says, it will be hard. It says, sometimes you lose. It says, sometimes the cost is high. But it also says, never, ever give up, because no corrupt empire, no tyrant-king, no evil ever lasts forever.)

That’s why Fantasy.

The post Why Fantasy? Because It Saved Me appeared first on Every Book a Doorway.

April 29, 2020

Wyrd & Wonder: A month of all things fantasy!

Phoenix art credit Sujono Sujono!

This is my first time taking part in Wyrd & Wonder, an annual month-long celebration of the fantasy genre hosted by Jorie, Lisa, and imyril! And I mean…come on. It’s ALL THINGS FANTASY. Of course I had to join in! Fantasy is my life.

A whole bunch of other bloggers will be taking part too, and the Wyrd & Wonder team have prepared post prompts and quests, some of which I’ll definitely be making use of. I have book rec lists and some essay-type things I want to get written up, as well as a whole bunch of reviews I need to finish, and I’m really excited for all of it!

And maybe I’ll even finally get around to writing about Book Witchery – after all, what’s more fantastical than real life magic?

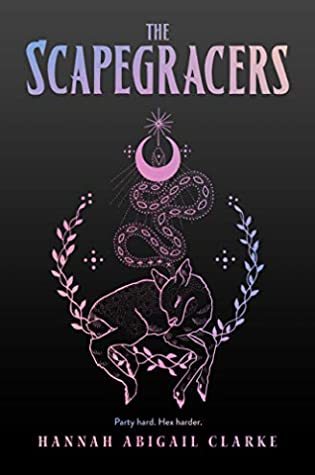

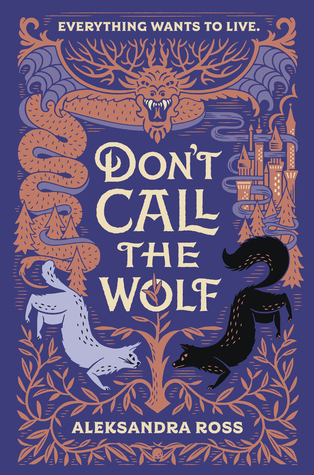

As for a tentative TBR for May, behold!

Books I’ve Started and Need to Finish

TBRR (To Be Read once Released!)

(ie, books coming out in May that I’m REALLY REALLY EXCITED ABOUT AND CAN’T WAIT TO READ)

Who else is taking part? Are any of you reading (or planning to read) any of the books above? Let me know!

The post Wyrd & Wonder: A month of all things fantasy! appeared first on Every Book a Doorway.

April 8, 2020

The currents beneath the sea, plus dragons: Phoenix Extravagant by Yoon Ha Lee

Representation: Characters of Colour, Non-Binary MC, Polyamory (secondary characters), f/f or wlw (secondary characters)

Published by Solaris on 9th June 2020

Genres: Fantasy

Pages: 416

Buy on Amazon, The Book Depository

Goodreads

For generations the empire has spread across the world, nigh-unstoppable in their advance. Its power depends on its automata, magically animated and programmed with sigils and patterns painted in mystical pigments.

A symbol-painter – themselves a colonial subject – is frustrated in their work when their supply of Phoenix Extravagant dries up, and sets out to find the source. What they’ll discover is darker than anything they could have imagined…

Thank you to NetGalley and the publisher for the ARC!

Wow. I finished this book just a few minutes ago, and I’m reeling. In the best way! But I’m not at all sure how to describe what I just experienced.

First off, Phoenix Extravagant took me completely by surprise; it was not the book I was expecting. I was incredibly excited when I heard that Lee was writing a fantasy novel, because the creativity demonstrated in his sci-fi is incredible, even though I bounced off those books (I’m not much of a sci-fi reader, and they are pretty heavy sci-fi). So, thinks I, now he’s writing fantasy I have a much better chance of being able to properly appreciate him! Because fantasy is my genre, even when it gets properly weird. This one, I’ll be able to read and be wow-ed by!

And I did! I was! This was much easier to sink into than Ninefox Gambit, and I enjoyed it immensely. But I was expecting the wild, outside-the-box, wildly-inventive creativity of Ninefox, and that’s not what this book is. Or no, that’s not right; it’s that Ninefox is immediately and obviously out there. You can’t miss the fact that it’s like nothing else you’ve ever read, because the alien strangeness is in your face from the first paragraph.

Phoenix Extravagant is also like nothing else I’ve ever read, but in a much subtler way. Superficially, the world and story of PE is fairly recognisable, even standard; the setting is obviously inspired by eastern Asia, and the magic system takes the form of a series of glyphs painted in special inks – it’s very reminiscent of computer code. A few small but delightful details stand out – one of the minor characters is a gumiho, the Korean equivalent of a kitsune, a shapeshifting fox-spirit, and her presence in society is completely normalised, a conceit that delighted me; as did the presence of the Celestials living on the moon, visible going about their lives through telescopes. But for the most part, neither the worldbuilding nor magic system are what makes this story special.

I hardly have the words to explain what it is that makes PE such a heavy hitter. I mean that literally; I don’t know what to call the primary movers and shakers of the story. Cultural forces, maybe? Phoenix Extravagant is like an ocean that is calm on the surface, but has deep and powerful currents running just beneath what’s visible. It’s about the give and take of different cultures, of shifting cultures, of cultural values and those things that are valuable to a culture (not always the same things). It’s about appropriation and assimilation, patriotism versus practicality, conquerors against the conquered. Those are the things powering the plot, driving the story and the characters within it. Those are the things that sweep you up and drag you in and keep you up late at night, turning pages as quickly as you can.

On the surface, this is a story about Jebi, a non-binary/third-gender artist of Hwaguk, a country that was conquered by the Empire of Razan six years before the book opens. Unlike their older sister, Jebi is, if not quite indifferent to Hwaguk’s vassalage, more or less at peace with it: this is the world they live in now, and they mean to succeed in it as best they can. That means paying the substantial fee to register themselves with a Razanei name – Tesserao Tsennan – and applying for a job in the now Razanei-run Ministry of Art, both things their sister Bongsunga would view as betraying their people, and unforgivable. Which is fair enough, given that Bongsunga’s wife died in the war, but Jebi knows that working with/for the Razanei is the only way they’re ever going to be able to support themself, instead of living on Bongsunga’s charity forever.

Through a tricky little knot of events and behind-the-scenes subterfuge, Jebi ends up working for the Ministry of Armor instead of the Ministry of Art, their artistic skills put to use in the creation of Razan’s magically-powered automata – which police the streets – instead of in propaganda posters or the like. And as the book’s blurb states, Jebi discovers the horrible secret behind the creation of the inks the Razanei use to create those automata…

But, see, it’s not the horrible secret you’re probably guessing it is. It’s arguably worse. And I can’t talk about it without giving too big a spoiler, but it’s that unexpected twist that sets the tone for the entire book, the linchpin of the whole story. And I’m so impressed with it, and the way it’s woven through the book, how all those cultural forces I mentioned tangle and twine with each chapter.

This book wasn’t what I expected. I seriously doubt it’s what anyone is expecting, given the blurb it was given, which isn’t lying but is definitely misleading – or possibly lying by omission. But for the best of reasons. If the blurb explained what’s actually going on in PE, it would sound so dull to most readers, and it isn’t. I don’t know that I could spin it in a way that makes it exciting either, but Lee has written it all in a way that’s un-put-downable – not because it’s non-stop action and fight scenes, but because he’s an incredible writer who makes even the slower, quiet moments resound with the reader.

Oh, and there’s a dragon. An utterly fabulous dragon. But I’m willing to bet it’s not the kind of dragon – or character – you’re already expecting it is.

It’s not Pacific Rim. It’s not an anime. But it’s a powerful, deeply moving book that is a wonderful read, without question one of the best of the year. I can’t wait until it’s out so I can talk to other people about it properly!

The post The currents beneath the sea, plus dragons: Phoenix Extravagant by Yoon Ha Lee appeared first on Every Book a Doorway.

March 23, 2020

(Very Belated!) International Women’s Day 2020 tag

Lauren from Library of Lauren (@chimchimjimins over on twitter!) tagged me in the International Women’s Day 2020 tag by Dianthaa (Dianthaa Dabbles). I am EXTREMELY LATE, but that’s because I was banned from the computer for almost two weeks, on doctor’s orders. (Repetitive strain injury to my wrist. Blegh. But all’s well now!)

ANYWAY. Much thanks to Lauren! Even though this is terribly late, I had a lot of fun with it

March 3, 2020

Could have been perfect: The Girl of Hawthorn and Glass

Representation: Pansexual lead, NB/Genderqueer, Gay Male, past F/F

on 16th May 2020

Genres: Urban Fantasy

Buy on Amazon, The Book Depository

Goodreads

Even teenage assassins have dreams.

Eli isn’t just a teenage girl — she’s a made-thing the witches created to hunt down ghosts in the human world. Trained to kill with her seven magical blades, Eli is a flawless machine, a deadly assassin. But when an assignment goes wrong, Eli starts to question everything she was taught about both worlds, the Coven, and her tyrannical witch-mother.

Worried that she’ll be unmade for her mistake, Eli gets caught up with a group of human and witch renegades, and is given the most difficult and dangerous task in the worlds: capture the Heart of the Coven. With the help of two humans, one motorcycle, and a girl who smells like the sea, Eli is going to get answers — and earn her freedom.

This book was so beautiful…and so messy. I went in wanting to love it so badly; it sounded like it had been written for me! But it ended up being a serious struggle to finish, and to be honest if it had been any other book I would have DNF-ed it. I gave this one way more chances than I do most of my reads.

Eli was made, not born, by the witches of the City of Eyes – another world not so very far from our own. Eli’s task is to hunt down ghosts in the human world and kill them with her seven magical daggers, each of which has its own special power – and Eli is very, very good at what she does. But one day a hunt goes wrong, starting Eli on a road that will uncover the darkest secrets of the City of Eyes and entangle her in the cause and fate of an underground rebellion.

There’s so much to love about The Girl of Hawthorn and Glass; the world Jerreat-Poole has created is weird and wonderful, full of fierce and otherworldly magic. There’s the living Labyrinth that overlays the City of Eyes, the Children’s Lair, the gemstone books in the Coven’s library and Eli’s daggers of pearl and glass and thorns. When Jerreat-Poole turns on the descriptions, they’re lovely and different, not falling back on familiar similes but making strange and dazzling new ones. And there’s so many bits of the worldbuilding that I adored; the wild, feral children hiding in the depths of the Labyrinth, the truth about the ghosts, the fact that witches have to go on quests to the human world to steal themselves names, since they’re born without any of their own. And Hawthorn and Glass is casually but powerfully queer, with non-binary characters at the forefront and a deeply important f/f relationship in Eli’s past – not to mention Cam, who was drawn into the world of magic when he fell hard for a male witch.

But…

It feels like this book just isn’t finished. It moves too quickly, and too much goes completely unexplained. The mysteries presented to the reader aren’t the kind that make you want to keep reading to get answers; they’re just frustratingly confusing, and the answers, when they come at all, aren’t satisfying. Vital pieces of the worldbuilding are dropped into the narrative without explanation – the Heir, the Heart of the Coven, the Warlord; I still have barely any idea what any of them are or how they work, despite all of them being intrinsic to the plot and its conclusion. None of the character motivations/drives felt very developed, except maybe for Tav’s; Eli requires almost no convincing to turn on everything she’s ever known, and I honestly have no clue whatsoever what the hells Kite was up to the entire time.

And there’s just. No explanation for why, or how, Tav breaks all the rules about magic. Maybe that’s meant to be explained in the sequel, but as-is it was just maddening, and came out of nowhere.

I wish there’d been more introspection, more description. I wish the book were longer, so that it could have moved more slowly; the plot feels so rushed, which is such a shame when the bones of a really incredible story are there beneath everything.

I still think that a lot of readers are going to enjoy the hell out of this one; there’s enough here to really appeal to readers who aren’t as obsessive or nit-picky as I am. But for me, this one was a disappointment.

The post Could have been perfect: The Girl of Hawthorn and Glass appeared first on Every Book a Doorway.