Jane Alexander's Blog, page 4

December 23, 2014

Holiday reading

What I should be reading over the festive period:

What I’m planning to read over the festive period:

What I’ll manage to read over the festive period, if I’m lucky:

December 12, 2014

Writer’s block? Why an art class might help…

Writing is necessarily solitary, and though I get to meet all kinds of interesting people through teaching creative writing, opportunities to share experiences with, and learn from, other writer-teachers can be hard to come by. So it was exciting to attend my first National Association of Writers in Education conference a couple of weeks back, and to find myself surrounded by hundreds of other professional ‘writers in education’. Over three days of seminars, workshops and presentations we covered subjects ranging from flash fiction for beginner writers, with the hugely enthusiastic Carrie Etter, to storytelling with military veterans.

One of the most surprising sessions for me focused on the benefits of integrating drawing with your writing practice. Though there are plenty of accomplished writer-artists (strangely, the examples that spring to mind are all Scottish: John Byrne, Alasdair Gray, Ian Hamilton Findlay…) I’ve tended to think of drawing and writing as mutually exclusive activities. Drawing is about looking – looking hard – and if I’m working on a piece of writing I’m usually oblivious to the detail of the world around me, because I’m so thoroughly absorbed in the world I’m imagining.

So what was surprising about the activities our experts (Patricia Ann McNair and Philip Hartigan from Columbia College Chicago) asked us to try? After some scribbly warm-ups, we made ‘blind mono’ drawings of something or someone in the room – line drawings made without looking at the subject and without lifting pen from paper. And while we drew, we were supposed to think about a piece of writing we were working on. Holding those two activities in my head at the same time was a challenge, and I didn’t feel I managed it very well. But then we turned over our paper and began a ‘blind writing’, working fast and covering up each line of text as soon as we’d written it – and I was amazed at how fluently ideas arrived for a a story that had been stuck for a while at the ‘vague inspiration’ stage.

My ‘blind mono’ drawing

My ‘blind mono’ drawingPhilip and Patricia suggested this effect may be to do with a physical openness, a loosening up that transfers itself from the physical process of drawing to the more static, hunched-over business of writing. Perhaps it’s as simple as using movement to shake the ideas loose, in the same way that going for a walk can unstick you creatively. And I’m not sure how it would work with writers who haven’t drawn since school, who might well have negative preconceptions about their ability to draw ‘well’. But – even though I’m quite pleased with my blind mono – this isn’t about drawing well: what I learned was that you have to let go of the idea of making a good picture, to make good writing.

November 21, 2014

Music to write books by

Apparently mild ambient noise can encourage creativity. This rings true for me: swapping my study or the quiet floor of the library for a coffee-shop often lifts me into a writing zone. I’ve always thought it’s something to do with forgetting your self; sometimes silence is too self-conscious.

Rainy Day Cafe is a great alternative to spending a fortune on Americanos, and less likely to result in caffeine jitters. And music can work too – but it has to be the right music, which for me means no words, or words that are deeply buried in the music, or words in a foreign language. I’ve started a playlist of my favourite music to write by, and the idea is to add to it till I have a whole day of inspiration. So to start off, Nick Cave and Warren Ellis (any of their soundtrack compositions work for me, but White Lunar brings together some of their best stuff, and is a great place to start listening); then, developing the Warren Ellis theme, a Dirty Three track from Whatever You Love, You Are.

November 13, 2014

Five reasons to be a writer-teacher

At a workshop last week I asked some of my creative writing students what they hoped to gain from their studies. You might think the answer would be obvious: I’d like to be a professional, published author. But interestingly, only one of a dozen students told me this was her goal, and the range of other reasons was much more wider than you might expect. They were learning variously for pleasure; to be able to use the skills of creative writing to enliven their academic or educational writing; to write a family history; to record their own lives for future generations; to try something new.

This diversity of ambition tends not to be considered in the conversation about whether or not creative writing can be taught. (As an ex-art student, I find it genuinely baffling that this is even a question when no-one seriously suggests that drawing, painting etc. might be unteachable; my favourite contribution to the debate comes from author Tim Clare: Can Creative Writing Be Taught? Not If Your Teacher’s A Prick.)

Anyway, this made me consider the question from my own perspective: what do I hope to gain from teaching creative writing? The obvious answer is an income, and that’s certainly a factor. But in five years of teaching all different kinds of learners, at all levels, I’ve found there are other benefits, too.

1) It makes you a more thoughtful writer. When I began teaching creative writing, I had to become much more consciously aware of the techniques and strategies I was using in my own work so I could explain and illustrate them to others. This increased self-awareness is like switching on the light so you can see what’s in your tool-kit. There are still times when I find myself fumbling around in the dark – and a bit of fumbling has its place – but once you’ve got electricity, it’s hard to imagine how you ever built a whole house by candlelight.

2) It unsticks you. Just occasionally during a conversation with a student, a lightbulb appears above my head as I realise the solution I’m suggesting to them is the very thing I need to apply to my own work-in-progress. One story had been perplexing me for years; then I had the lightbulb moment – to do with organising time – and it was finished that afternoon. And that solution worked for the student, too.

3) It makes you raise your game. When you realise how very many people there are out there who are talented writers bursting with inventive ideas, that’s a great incentive to work harder at developing your own skills – as well as a reminder that talent and inventiveness often need a third, less glamorous friend: persistence.

4) It gets you out of the house. Most of my days are spent reading, writing, thinking, procrastinating, going for walks and making tea – alone. I like alone, but I also like to be reminded from time to time that other people exist; that I exist. Teaching, especially with really varied groups, allows me to meet new people – to connect with the world outside my head.

5) It pays. Because unless you’re happy living in that garret, you’re going to need a day-job.

October 31, 2014

Ghost story season

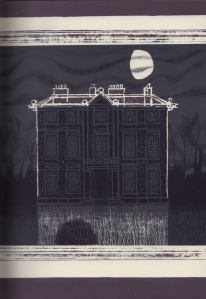

Last weekend the clocks went back, and today Hallowe’en seems to mark the start of the ghost story season. When it’s dark at 5pm, with autumnal weather held at a distance by the warmth and flicker of the wood-burning stove, there’s something comforting as well as creepy about sinking into tales of hauntings. At the moment I’m searching particularly for contemporary uncanny short stories, for the PhD I’ve just started; here, any ghosts are as likely to be found haunting new technologies as crumbling old houses. But I’ll find time to revisit some classics, too. Last winter I bought a beautiful Folio edition of Ghost Stories of M.R. James, which I love as much for the illustrations as for the text. In these lithographs by Charles Keeping the palette is strictly limited, the textures are rich, and the images subtle – gesturing towards the half-glimpsed horrors of James’s tales.

Last weekend the clocks went back, and today Hallowe’en seems to mark the start of the ghost story season. When it’s dark at 5pm, with autumnal weather held at a distance by the warmth and flicker of the wood-burning stove, there’s something comforting as well as creepy about sinking into tales of hauntings. At the moment I’m searching particularly for contemporary uncanny short stories, for the PhD I’ve just started; here, any ghosts are as likely to be found haunting new technologies as crumbling old houses. But I’ll find time to revisit some classics, too. Last winter I bought a beautiful Folio edition of Ghost Stories of M.R. James, which I love as much for the illustrations as for the text. In these lithographs by Charles Keeping the palette is strictly limited, the textures are rich, and the images subtle – gesturing towards the half-glimpsed horrors of James’s tales.

Uncertainty is the currency of the best ghost stories: danger is always more terrifying when it’s suggested, rather than made explicit; where the author conceals what we urgently want (and don’t want, just as urgently) to see. The leaving-out is just as important as the putting-in: as is so often the case with stories, and pictures too, it’s all about knowing when to stop.