Nuala Ní Chonchúir's Blog, page 13

November 8, 2015

The 4 Best Ways to Fuck-up Your Poetry Reading

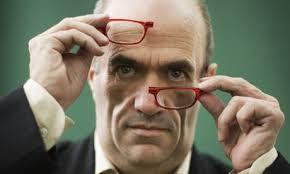

Patrick Cotter, IMO the best arts administrator in Ireland (he's director of Munster Lit) is also a poet, writer and blogger. He has a brilliant new post on his blog for poets. His advice also applies to fiction writers. Below is the first bit, to whet your appetite. Go here for the rest.

1 Make like it's 1983

Strange to think it, but there are still poets out there who deliver their poems in a monotonous monotone. Most of them tend to be over fifty years of age. Last century (literally) it was de rigeur to give a poetry reading in a monotone – I guess it was a reaction against the way many actors can mangle a poem as they declaim it. Most poets hate the way most actors read poetry. Somebody wise once observed that most poets, when saying a poem aloud, do so by moving from consonant to consonant whereas most actors move from vowel to vowel. Jeremy Irons is a lovely man but he is the stereotypical example of an actor who knows how to destroy a poem, especially one by Yeats, by stretching out every vowel like a dog’s yowl. Anyhow last century the way most poets mitigated against this particular trauma was to put no feeling at all or variation of tone into the public reading of a poem. To inject feeling into a poem was believed to get between the audience and the poem; to impose an interpretation. It was believed by many that if you delivered a poem in a monotone the audience could concentrate specifically on the words and react in their own chosen way as they might by absorbing words straight off the page.

Famously Paul Celan met with sneering disapproval when he read his poems in the traditional Eastern European shamanistic style (with feeling) to a group of German poets in Hamburg in 1952. One observer said Celan had sounded just like Goebbels, another said he sounded like he was singing in the synagogue. Amazingly, this attitude to reading poetry was not confined by the borders of Germany – it was fairly common throughout the English-speaking world too and was the most dominant reading style right up to the beginning of this century.

Slam and performance poetry shook the whole scene up – demonstrating how large audiences would react better to a bit of life in your voice as you declaimed your poem. Sadly there are still older poets who make it like it’s 1983 – often brilliant, insightful, exciting poets on the page who destroy their own reputations as soon as they open their mouths in a crowded auditorium – these days even frequent readers of poetry, even gifted, sophisticated younger ‘page’ poets no longer possess the ability to ‘read’ a poem aurally in a monotone. Monotone poets rarely receive repeat invitations to read and curators elsewhere get to hear how boring they sound and drop them from their thoughts too.

See points 2, 3 and 4 here.

1 Make like it's 1983

Strange to think it, but there are still poets out there who deliver their poems in a monotonous monotone. Most of them tend to be over fifty years of age. Last century (literally) it was de rigeur to give a poetry reading in a monotone – I guess it was a reaction against the way many actors can mangle a poem as they declaim it. Most poets hate the way most actors read poetry. Somebody wise once observed that most poets, when saying a poem aloud, do so by moving from consonant to consonant whereas most actors move from vowel to vowel. Jeremy Irons is a lovely man but he is the stereotypical example of an actor who knows how to destroy a poem, especially one by Yeats, by stretching out every vowel like a dog’s yowl. Anyhow last century the way most poets mitigated against this particular trauma was to put no feeling at all or variation of tone into the public reading of a poem. To inject feeling into a poem was believed to get between the audience and the poem; to impose an interpretation. It was believed by many that if you delivered a poem in a monotone the audience could concentrate specifically on the words and react in their own chosen way as they might by absorbing words straight off the page.

Famously Paul Celan met with sneering disapproval when he read his poems in the traditional Eastern European shamanistic style (with feeling) to a group of German poets in Hamburg in 1952. One observer said Celan had sounded just like Goebbels, another said he sounded like he was singing in the synagogue. Amazingly, this attitude to reading poetry was not confined by the borders of Germany – it was fairly common throughout the English-speaking world too and was the most dominant reading style right up to the beginning of this century.

Slam and performance poetry shook the whole scene up – demonstrating how large audiences would react better to a bit of life in your voice as you declaimed your poem. Sadly there are still older poets who make it like it’s 1983 – often brilliant, insightful, exciting poets on the page who destroy their own reputations as soon as they open their mouths in a crowded auditorium – these days even frequent readers of poetry, even gifted, sophisticated younger ‘page’ poets no longer possess the ability to ‘read’ a poem aurally in a monotone. Monotone poets rarely receive repeat invitations to read and curators elsewhere get to hear how boring they sound and drop them from their thoughts too.

See points 2, 3 and 4 here.

Published on November 08, 2015 01:54

November 7, 2015

Historical Novel Society *Miss Emily* feature

I'm very pleased that Arleigh Johnson has a feature in the Historical Novels Review, and online at the Historical Novel Society site, about Miss Emily and the use of real vs fictional characters. It's here but for members only, so here's the content below. I hope it's OK for me to re-blog it. I'll find out soon enough if not, no doubt.

Nuala O’Connor’s Miss Emily: Real Versus Fictional CharactersARLEIGH JOHNSON

Narrating a novel in the voice of a well-known historical figure can be a daunting task. One must be both true to historical fact while giving the fictionalized version a believable and engaging persona. Another pitfall, especially when reimaging a writer’s life, may be the use of too many phrases from the author’s works, thus taking away the opportunity to give a fresh perspective on a well-studied subject.Miss Emily (Penguin US, Sandstone UK, 2015) avoids monopolizing poetic verses, using instead clever reasoning behind the characters’ actions and ponderings that relate to recorded words and peculiarities of the historical people.Based on a period during the life of American poet and writer Emily Dickinson, the story follows two protagonists: Emily herself, and a fictional character from O’Connor’s own hometown in Ireland. Ada Concannon, a newly arrived Irish immigrant, is looking for work while staying with her Amherst, Massachusetts relatives. The Dickinsons are without a maid, and Emily and her sister have been dividing the chores, which leaves little time for other pursuits. It is with much relief that Ada is hired, ultimately moving in with the family to take care of kitchen and laundry duties, as well as other chores.Emily, surprisingly to those not acquainted with the poet’s personal life, loved to bake, and she spends time in the kitchen with Ada, forming a bond between the women that is frowned upon by the elder Dickinsons. Emily’s brother, Austin, is portrayed as especially vehement about separating the social classes and behaving accordingly, although this was one of O’Connor’s fictions. She explains: “In reality, I think he was a much more fair-minded, generous, and genteel man than I have made him in my book, but I needed to serve the plot.” In fact, much of the conflict in the story deals with Emily’s shying away from Amherst society and withdrawing into her small circle, of which Ada becomes an increasingly important part. The kitchen comes to be a sanctuary for both women; for one as the means of living an independent life, and quite the opposite for the other. For Emily, it is sharing a part of herself that no one — not even her mother, sister or beloved sister-in-law, Susan — has witnessed.Ada, as a fictitious addition to Emily’s world, provides much needed malleability as a character, which helps meet O’Connor’s creative demands. “It turned out [Emily] did have Irish maids, but I invented a new one so that I would not be working two real lives into fiction. I needed some room to imagine.” The author achieves a link between Emily and Ada by giving them similar traits, such as an interest in nature and a way with words. Ada is no poet, but her plain, blunt dialog sprinkled with her mother’s Irish sayings and superstitions gives inspiration to Emily, igniting the poet’s curiosity and muse. In the author’s words, “They are noticers — nothing escapes them.”This novel, written in dual voices, works exceedingly well in blending fact and fiction. For those with a cursory knowledge of Dickinson’s life and poetry, the imagined content fits pleasingly with the mid-19th century setting. The poet’s verses, though cleverly interlaced within the narrative in various forms, are not noticeable replicas, as has been apparent in similar fictional biographies. A refreshing take on one of the noted periods of her life — Emily’s famous transition to wearing only white — is deftly woven into the story with thought and humor, as is her habit of distributing gingerbread cookies to the children in the neighborhood. Readers are given an admirable and respectable impression of a character who could as easily be seen as an odd recluse. Without both perspectives, there wouldn’t be an endearing depth of feeling between the characters. Ada’s inclusion, as a blank page to Emily’s strictly documented existence, works as an effective tool in creating an enthralling biographical novel.

Narrating a novel in the voice of a well-known historical figure can be a daunting task. One must be both true to historical fact while giving the fictionalized version a believable and engaging persona. Another pitfall, especially when reimaging a writer’s life, may be the use of too many phrases from the author’s works, thus taking away the opportunity to give a fresh perspective on a well-studied subject.Miss Emily (Penguin US, Sandstone UK, 2015) avoids monopolizing poetic verses, using instead clever reasoning behind the characters’ actions and ponderings that relate to recorded words and peculiarities of the historical people.Based on a period during the life of American poet and writer Emily Dickinson, the story follows two protagonists: Emily herself, and a fictional character from O’Connor’s own hometown in Ireland. Ada Concannon, a newly arrived Irish immigrant, is looking for work while staying with her Amherst, Massachusetts relatives. The Dickinsons are without a maid, and Emily and her sister have been dividing the chores, which leaves little time for other pursuits. It is with much relief that Ada is hired, ultimately moving in with the family to take care of kitchen and laundry duties, as well as other chores.Emily, surprisingly to those not acquainted with the poet’s personal life, loved to bake, and she spends time in the kitchen with Ada, forming a bond between the women that is frowned upon by the elder Dickinsons. Emily’s brother, Austin, is portrayed as especially vehement about separating the social classes and behaving accordingly, although this was one of O’Connor’s fictions. She explains: “In reality, I think he was a much more fair-minded, generous, and genteel man than I have made him in my book, but I needed to serve the plot.” In fact, much of the conflict in the story deals with Emily’s shying away from Amherst society and withdrawing into her small circle, of which Ada becomes an increasingly important part. The kitchen comes to be a sanctuary for both women; for one as the means of living an independent life, and quite the opposite for the other. For Emily, it is sharing a part of herself that no one — not even her mother, sister or beloved sister-in-law, Susan — has witnessed.Ada, as a fictitious addition to Emily’s world, provides much needed malleability as a character, which helps meet O’Connor’s creative demands. “It turned out [Emily] did have Irish maids, but I invented a new one so that I would not be working two real lives into fiction. I needed some room to imagine.” The author achieves a link between Emily and Ada by giving them similar traits, such as an interest in nature and a way with words. Ada is no poet, but her plain, blunt dialog sprinkled with her mother’s Irish sayings and superstitions gives inspiration to Emily, igniting the poet’s curiosity and muse. In the author’s words, “They are noticers — nothing escapes them.”This novel, written in dual voices, works exceedingly well in blending fact and fiction. For those with a cursory knowledge of Dickinson’s life and poetry, the imagined content fits pleasingly with the mid-19th century setting. The poet’s verses, though cleverly interlaced within the narrative in various forms, are not noticeable replicas, as has been apparent in similar fictional biographies. A refreshing take on one of the noted periods of her life — Emily’s famous transition to wearing only white — is deftly woven into the story with thought and humor, as is her habit of distributing gingerbread cookies to the children in the neighborhood. Readers are given an admirable and respectable impression of a character who could as easily be seen as an odd recluse. Without both perspectives, there wouldn’t be an endearing depth of feeling between the characters. Ada’s inclusion, as a blank page to Emily’s strictly documented existence, works as an effective tool in creating an enthralling biographical novel.

Published on November 07, 2015 01:45

November 5, 2015

MISS EMILY ON IRISH NOVEL OF THE YEAR SHORTLIST

I am thrilled beyond the beyonds that Miss Emily is on the shortlist for the Easons Book Club Irish Novel of the Year along with books by Edna O'Brien, Anne Enright, Paul Murray, Belinda McKeon and Kevin Barry, in the Bord Gáis Energy Irish Book Awards. And you can vote for your favourites!

The Long Gaze Back womens' story anthology is also shortlisted, in the Best Published Book of the Year category, which is an extra thrill.

Ger Holland took this pic of Declan Meade and me. Love it.

Ger Holland took this pic of Declan Meade and me. Love it.

There was a lovely ceremony in the Bord Gáis Energy Theatre in Dublin yesterday to announce all the shortlists. Ger Holland took lots of great pics which you can look at on the writing.ie Facebook page here. The Big Night is the 25th, when the winners will be announced. The public part of the Book Awards vote is now open here.

And in today's Irish Times, the sublime Sinéad Gleeson interviews me about Miss Emily. It's here.

The Long Gaze Back womens' story anthology is also shortlisted, in the Best Published Book of the Year category, which is an extra thrill.

Ger Holland took this pic of Declan Meade and me. Love it.

Ger Holland took this pic of Declan Meade and me. Love it.There was a lovely ceremony in the Bord Gáis Energy Theatre in Dublin yesterday to announce all the shortlists. Ger Holland took lots of great pics which you can look at on the writing.ie Facebook page here. The Big Night is the 25th, when the winners will be announced. The public part of the Book Awards vote is now open here.

And in today's Irish Times, the sublime Sinéad Gleeson interviews me about Miss Emily. It's here.

Published on November 05, 2015 00:29

November 3, 2015

TV INTERVIEW - MISS EMILY

Here's the link to my TV interview about Miss Emily with TG4 on their arts show, Imeall. It is viewable for the next month. (I'm first on the programme.) Tristan Rosenstock and cameraman Paschal came to my home to interview me. The Emily scenes were shot in Strokestown House, Co. Roscommon.

Published on November 03, 2015 00:00

November 2, 2015

Colm Tóibín International Short Story Award

Colm Tóibín - pic by the Guardian

Colm Tóibín - pic by the GuardianI'm delighted to be on the judging panel, along with Vanessa Fox O'Loughlin and Lisa Coen, for the inaugural Colm Tóibín International Short Story Award.

Word count: 1800 - 2000 words

Closing date: 31st May 2016

Prize: €1000 first prize, €500 second, €350 third prize.

All details here.

Published on November 02, 2015 01:25

October 30, 2015

CRANNÓG 40 & WOMAN'S WAY

Crannóg 40 - cover art by Robert BallaghI'll be reading at the launch of Crannóg's 40th issue tonight in The Crane Bar in Galway. The Crannóg crew are the pre-eminent Galway lit group, always going about their business in style.

Crannóg 40 - cover art by Robert BallaghI'll be reading at the launch of Crannóg's 40th issue tonight in The Crane Bar in Galway. The Crannóg crew are the pre-eminent Galway lit group, always going about their business in style.*

I'm in Woman's Way this week, yapping about my favourite books (some of them).

Click and zoom to read

Click and zoom to read

Published on October 30, 2015 02:11

October 29, 2015

IMEALL & BLACKBIRD BOOKS

Blackbird Books posted this cute pic on TwitterI'm bi-locating tonight. I will simultaneously be on TV on Imeall, TG4's arts programme, at 8pm and I will also be in Blackbird Books in Navan reading from Miss Emily, with Jax Miller. It looks like a lovely spot, I'm excited to see it.

Blackbird Books posted this cute pic on TwitterI'm bi-locating tonight. I will simultaneously be on TV on Imeall, TG4's arts programme, at 8pm and I will also be in Blackbird Books in Navan reading from Miss Emily, with Jax Miller. It looks like a lovely spot, I'm excited to see it.The Imeall crew were sweethearts - Tristan Rosenstock came to my house to interview me with cameraman Paschal. I will be interested to see the piece (if only cringily, through my fingers).

Published on October 29, 2015 02:00

October 28, 2015

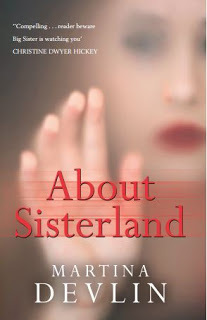

MARTINA DEVLIN - ABOUT SISTERLAND - INTERVIEW

I used to think I didn’t like futuristic novels but I’ve lately been blown away by two: Station Eleven by Emily St John Mandel and

About Sisterland

by Martina Devlin, published by Dublin literary imprint Ward River Press. I’m delighted to welcome Martina to the blog today to talk about her book.

Author Martina DevlinAbout Sisterland is an atmospheric, thoughtful, intriguing look at the pitfalls of gender dominated society, in this case, a world ruled by women. There is nothing usual about this book, especially in an Irish context where we are obsessed with our very Irishness. The characters in About Sisterland have a whole other set of land, geography and identity questions to grapple with.

Author Martina DevlinAbout Sisterland is an atmospheric, thoughtful, intriguing look at the pitfalls of gender dominated society, in this case, a world ruled by women. There is nothing usual about this book, especially in an Irish context where we are obsessed with our very Irishness. The characters in About Sisterland have a whole other set of land, geography and identity questions to grapple with.

Martina was born in Omagh and makes her home in Dublin She has had nine books published; other novels include The House Where It Happened, a ghost story inspired by Ireland's only mass witchcraft trial, and Ship of Dreams, about the Titanic disaster. Prizes include the Royal Society of Literature's VS Pritchett Prize and a Hennessy Literary Award, while she was twice shortlisted for the Irish Book Awards. A current affairs commentator for the Irish Independent, she has been named columnist of the year by the National Newspapers of Ireland. Martina is vice-chairperson of the Irish Writers Centre.

Welcome, Martina. It’s a pat and, sometimes, unwelcome question to ask a writer, so apologies in advance, but where did this novel spring from?

From two sources. First, because I grew up in the North of Ireland during the Troubles, where I observed how two communities led separate lives (not educated together, not living in the same areas) which created the space for extremism to put down roots. I’m not suggesting that everyone saw the other side as entirely ‘other’ and separate, but the potential was there. Second, from reading the work of a groundbreaking social activist and feminist, Charlotte Perkins Gilman. She wrote an extraordinary short story – ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’ – about postnatal depression long before it was acknowledged as a condition. But what helped to inspire About Sisterland was her novel, Herland, written 100 years ago and serialised in a magazine she published. It imagines a world ruled by women – a utopia. There are no negatives. I mulled that over, and reached the opposite conclusion because women are people and people are never perfect. Least of all when they lay claim to it. I combined those ideas with a pet hate which is ‘isms’ and decided to look at extreme versions of some isms including fundamentalism and feminism.

The novel unfolds effortlessly but at a great pace. As a writer who doesn’t plot much I am always curious about other writers’ approach to plot. Can you talk a little about building About Sisterland?

I don’t plot much either. It doesn’t work for me. I begin with a character who interests me, and consider the potential journey he or she might make; also, I have a broad outline in my head of what a prospective novel might be about – some themes I’d like to explore. And then I leave myself open (hopefully) for inspiration to shape the novel once I’m immersed in the writing process. With this book, more than any other I’ve written, I saw pictures unfurl in my mind like petals opening to the sun. I had a very clear image of a harmonious and beautiful yet fundamentally dreadful (because totalitarian) society. Some of it came quickly once I began to write: the emphasis on controlling emotions which leads to rationing; the segregation of the sexes which helps to bring about the breakdown of the family unit; the communal child rearing for indoctrination purposes; the use of memory control to impose conformity. But other elements were more gradual and only emerged from draft after draft, such as how and why fantasy would be allowed in matingplace. I was never entirely sure how the novel would end while I was writing it.

Concrete naming is important in About Sisterland and everything, from people to places to procreative sex, are named with flair and imagination; you write about babyfusion (pregnancy), moes (emotions), Himtime (sex for conception) and many more brilliantly conceived terms. How did you approach the crucial business of naming things?

Language is fluid so I thought it likely that many of today’s familiar terms would be replaced in a future society. Once I began, it was a lot of fun for me. I’ve always liked to make up words anyhow. This gave me carte blanche. Babyfusion was the first term I invented, and I intended it both as a positive and negative. It plays with the idea of the child and mother (or source, as I call her) being combined until birth, with the utter dependendcy of the unborn child. But I wanted to suggest an unusual relationship between the two in Sisterland, due to the highly stratified society, and fusion has a word association with nuclear fusion and the negative implications of the atomic bomb. Lia Mills, who read an early version, suggested ‘meet’ to me for men chosen to mate because it suggests ‘meat’ which dehumanises the men. As, indeed, Sisterland does dehumanise them.

I kept thinking about celebrity culture as I read the book, as much as about the patriarchy. Was the revering of celebrities on your mind as you wrote?

Not initially, but as the book took shape it began to occur to me – in the sense that human beings seem to need to invent deities. Humankind alone is rarely enough for people. And celebrities have certainly acquired godlike status in today’s society. We iconise people who are important to our culture. I was also thinking about how information is manipulated, Magdalene laundries, what happens when the oppressed become the oppressor, asylum seekers, and how women around the world are denied education and persuaded or forced to cover themselves in public. In Sisterland, it’s the men who are illiterate and obliged to cover up. Dermot Bolger made me laugh recently. He said: “How on earth do you women treat men in Omagh?” That’s my hometown. But, of course, Sisterland is nowhere and everywhere.

Lia Mills interviewed me last year and began with the bald question ‘Why are you a writer?’ It’s a good question so, Martina, why are you a writer?

I think of myself as a storyteller rather than a writer and that applies to whatever kind of writing I’m doing, whether a newspaper column, radio essay, short story or novel. As to why I’m a storyteller, it’s because I grew up hearing stories from my parents. Whenever I think back to my childhood I hear their voices telling me about Cúchulain and other Celtic legends, or the stories from their own childhoods, or ghost stories. There were a lot of ghost stories by the fireside! The oral tradition was very strong, though we all read a lot as well. Libraries are my favourite place. I owe a great deal to them.

What is your writing process – morning or night – longhand or laptop?

Morning is best, even though I don’t think of myself as a morning person, and I write on a laptop. My cat Chekhov seems to enjoy hearing my fingers click on it and always positions himself in whichever room I’m working. He gives the appearance of snoozing while I work – but if I stop he opens his eyes and looks disapproving. He’s a very elegant slavedriver.

Who are your favourite women writers and why?

Brace yourself, it’s a long list. Jennifer Johnston, Margaret Atwood, Maria Edgeworth, Sarah Waters, Hilary Mantel, Catherine Dunne, Sylvia Townsend Warner, Joyce Carol Oates, Emma Donohoe, Marilynne Robinson, Christine Dwyer Hickey, Charlotte Bronte, Elizabeth Taylor, Virginia Woolf. I’ll stop now, although there are more. What they share in common is an ability to transport the reader to the time, place or situation they write about. In addition, I admire the way some of them switch genres from one book to the next – either because they choose not to be defined by genre or because they allow the story to dictate the genre.

What one piece of advice would you offer beginning writers?

Don’t write for the market. Write the kind of book you’d like to read. Even if you think it’s beyond your ability, stretch yourself and reach for that.

You are very diverse as a writer: you’re a journalist and your last novel before this was historical fiction. If it’s not too cheeky to ask, what can we expect from you next?

The journalism only takes up one day a week – it’s a toe in the water rather than all-consuming – an arrangement which allows me time and space for novels. In particular, I love historical fiction, especially the research – currently I’m spending a lot of time in Dublin’s National Library delving into the 1500s. The Pearse Library in Dublin is another useful resource. But it’s early days yet. Sometimes I walk away from projects after a period of research if the story doesn’t take shape in my mind. However, I do have a strong female character, an outsider, whose voice is becoming clearer to me every day. So fingers crossed.

Wishing you all the luck (and sales) in the world with About Sisterland, Martina. It’s a wonderful novel. Readers, you can buy it here, currently on sale for just €12.99.

Author Martina DevlinAbout Sisterland is an atmospheric, thoughtful, intriguing look at the pitfalls of gender dominated society, in this case, a world ruled by women. There is nothing usual about this book, especially in an Irish context where we are obsessed with our very Irishness. The characters in About Sisterland have a whole other set of land, geography and identity questions to grapple with.

Author Martina DevlinAbout Sisterland is an atmospheric, thoughtful, intriguing look at the pitfalls of gender dominated society, in this case, a world ruled by women. There is nothing usual about this book, especially in an Irish context where we are obsessed with our very Irishness. The characters in About Sisterland have a whole other set of land, geography and identity questions to grapple with.Martina was born in Omagh and makes her home in Dublin She has had nine books published; other novels include The House Where It Happened, a ghost story inspired by Ireland's only mass witchcraft trial, and Ship of Dreams, about the Titanic disaster. Prizes include the Royal Society of Literature's VS Pritchett Prize and a Hennessy Literary Award, while she was twice shortlisted for the Irish Book Awards. A current affairs commentator for the Irish Independent, she has been named columnist of the year by the National Newspapers of Ireland. Martina is vice-chairperson of the Irish Writers Centre.

Welcome, Martina. It’s a pat and, sometimes, unwelcome question to ask a writer, so apologies in advance, but where did this novel spring from?

From two sources. First, because I grew up in the North of Ireland during the Troubles, where I observed how two communities led separate lives (not educated together, not living in the same areas) which created the space for extremism to put down roots. I’m not suggesting that everyone saw the other side as entirely ‘other’ and separate, but the potential was there. Second, from reading the work of a groundbreaking social activist and feminist, Charlotte Perkins Gilman. She wrote an extraordinary short story – ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’ – about postnatal depression long before it was acknowledged as a condition. But what helped to inspire About Sisterland was her novel, Herland, written 100 years ago and serialised in a magazine she published. It imagines a world ruled by women – a utopia. There are no negatives. I mulled that over, and reached the opposite conclusion because women are people and people are never perfect. Least of all when they lay claim to it. I combined those ideas with a pet hate which is ‘isms’ and decided to look at extreme versions of some isms including fundamentalism and feminism.

The novel unfolds effortlessly but at a great pace. As a writer who doesn’t plot much I am always curious about other writers’ approach to plot. Can you talk a little about building About Sisterland?

I don’t plot much either. It doesn’t work for me. I begin with a character who interests me, and consider the potential journey he or she might make; also, I have a broad outline in my head of what a prospective novel might be about – some themes I’d like to explore. And then I leave myself open (hopefully) for inspiration to shape the novel once I’m immersed in the writing process. With this book, more than any other I’ve written, I saw pictures unfurl in my mind like petals opening to the sun. I had a very clear image of a harmonious and beautiful yet fundamentally dreadful (because totalitarian) society. Some of it came quickly once I began to write: the emphasis on controlling emotions which leads to rationing; the segregation of the sexes which helps to bring about the breakdown of the family unit; the communal child rearing for indoctrination purposes; the use of memory control to impose conformity. But other elements were more gradual and only emerged from draft after draft, such as how and why fantasy would be allowed in matingplace. I was never entirely sure how the novel would end while I was writing it.

Concrete naming is important in About Sisterland and everything, from people to places to procreative sex, are named with flair and imagination; you write about babyfusion (pregnancy), moes (emotions), Himtime (sex for conception) and many more brilliantly conceived terms. How did you approach the crucial business of naming things?

Language is fluid so I thought it likely that many of today’s familiar terms would be replaced in a future society. Once I began, it was a lot of fun for me. I’ve always liked to make up words anyhow. This gave me carte blanche. Babyfusion was the first term I invented, and I intended it both as a positive and negative. It plays with the idea of the child and mother (or source, as I call her) being combined until birth, with the utter dependendcy of the unborn child. But I wanted to suggest an unusual relationship between the two in Sisterland, due to the highly stratified society, and fusion has a word association with nuclear fusion and the negative implications of the atomic bomb. Lia Mills, who read an early version, suggested ‘meet’ to me for men chosen to mate because it suggests ‘meat’ which dehumanises the men. As, indeed, Sisterland does dehumanise them.

I kept thinking about celebrity culture as I read the book, as much as about the patriarchy. Was the revering of celebrities on your mind as you wrote?

Not initially, but as the book took shape it began to occur to me – in the sense that human beings seem to need to invent deities. Humankind alone is rarely enough for people. And celebrities have certainly acquired godlike status in today’s society. We iconise people who are important to our culture. I was also thinking about how information is manipulated, Magdalene laundries, what happens when the oppressed become the oppressor, asylum seekers, and how women around the world are denied education and persuaded or forced to cover themselves in public. In Sisterland, it’s the men who are illiterate and obliged to cover up. Dermot Bolger made me laugh recently. He said: “How on earth do you women treat men in Omagh?” That’s my hometown. But, of course, Sisterland is nowhere and everywhere.

Lia Mills interviewed me last year and began with the bald question ‘Why are you a writer?’ It’s a good question so, Martina, why are you a writer?

I think of myself as a storyteller rather than a writer and that applies to whatever kind of writing I’m doing, whether a newspaper column, radio essay, short story or novel. As to why I’m a storyteller, it’s because I grew up hearing stories from my parents. Whenever I think back to my childhood I hear their voices telling me about Cúchulain and other Celtic legends, or the stories from their own childhoods, or ghost stories. There were a lot of ghost stories by the fireside! The oral tradition was very strong, though we all read a lot as well. Libraries are my favourite place. I owe a great deal to them.

What is your writing process – morning or night – longhand or laptop?

Morning is best, even though I don’t think of myself as a morning person, and I write on a laptop. My cat Chekhov seems to enjoy hearing my fingers click on it and always positions himself in whichever room I’m working. He gives the appearance of snoozing while I work – but if I stop he opens his eyes and looks disapproving. He’s a very elegant slavedriver.

Who are your favourite women writers and why?

Brace yourself, it’s a long list. Jennifer Johnston, Margaret Atwood, Maria Edgeworth, Sarah Waters, Hilary Mantel, Catherine Dunne, Sylvia Townsend Warner, Joyce Carol Oates, Emma Donohoe, Marilynne Robinson, Christine Dwyer Hickey, Charlotte Bronte, Elizabeth Taylor, Virginia Woolf. I’ll stop now, although there are more. What they share in common is an ability to transport the reader to the time, place or situation they write about. In addition, I admire the way some of them switch genres from one book to the next – either because they choose not to be defined by genre or because they allow the story to dictate the genre.

What one piece of advice would you offer beginning writers?

Don’t write for the market. Write the kind of book you’d like to read. Even if you think it’s beyond your ability, stretch yourself and reach for that.

You are very diverse as a writer: you’re a journalist and your last novel before this was historical fiction. If it’s not too cheeky to ask, what can we expect from you next?

The journalism only takes up one day a week – it’s a toe in the water rather than all-consuming – an arrangement which allows me time and space for novels. In particular, I love historical fiction, especially the research – currently I’m spending a lot of time in Dublin’s National Library delving into the 1500s. The Pearse Library in Dublin is another useful resource. But it’s early days yet. Sometimes I walk away from projects after a period of research if the story doesn’t take shape in my mind. However, I do have a strong female character, an outsider, whose voice is becoming clearer to me every day. So fingers crossed.

Wishing you all the luck (and sales) in the world with About Sisterland, Martina. It’s a wonderful novel. Readers, you can buy it here, currently on sale for just €12.99.

Published on October 28, 2015 01:00

October 27, 2015

'WHAT EMILY WORE' ON SUNDAY MISCELLANY

Emily Dickinson doll by American Historical Society

Emily Dickinson doll by American Historical SocietyThe Sunday Miscellany Live programme I took part in in Donegal a few weeks ago was broadcast on Sunday on RTÉ Radio 1 - my piece is called 'What Emily Wore' and is about Emily Dickinson's clothes and image. Here's the link to the programme. I'm first up :) Also featured are Denise Blake and The Henry Girls, among others.

Published on October 27, 2015 05:06

October 22, 2015

SUNDAY MISC., RUFUS WAINWRIGHT & BIRR CASTLE

Sunday Miscellany Live, which I took part in in Donegal on the 4th October, will be broadcast over the next two Sundays. If it follows the order of recording, I'll be first up this Sunday, talking about Emily Dickinson's clothes. See here for more.

*

Tonight I head to Sligo for a very lovely event featuring Rufus Wainwright early tomorrow afternoon. He will give a talk on Creative Minds, hosted by the US Ambassador to Ireland at the Model at Niland. As many of you know I am a HUGE Rufus fan so it's a bit of a thrill to get an invitation to this. I even got to submit a question to Rufus in advance. If it's asked, I'll let ye know :) Then tomorrow night I'm at Rufus's Sligo Live gig. Excitement!

*

Sunday I'm reading from Miss Emily, and some Emily poetry, at a Gothic night in Birr Castle. Described on their website as follows:

The Twilight Hour – An evening of Gothic Music and Literature and Trickery with Nóirín Ní Riain & guests. Join us at Birr Castle for this very special evening with Nóirín Ní Riain and guests. Oíche Shamhna is a magical time with strong roots in ancient Celtic Ireland. This evening will celebrate music and literature linked to All Hallows Eve exploring much loved traditions, songs, folklore, ghost stories, poetry and lots of haunted fun in the gothic castle.

Booking essential as places are limited. Pre-paid event with Tickets €25.00.Adults only.

Published on October 22, 2015 01:27

Nuala Ní Chonchúir's Blog

- Nuala Ní Chonchúir's profile

- 41 followers

Nuala Ní Chonchúir isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.