Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 99

September 14, 2014

Historical novels seen at English historical sites

Although it may not have been apparent from this blog, I just got back from two weeks' vacation in England – Mark's and my first extended trip in some time. We flew into Heathrow, rented a car, and drove north, stopping at York, Durham, Alnwick, then Berwick upon Tweed, England's most northerly town... and then we turned around and headed back south, with an excursion to Hardwick Hall near Chesterfield.

I found it noteworthy that historical fiction had a presence in most of the gift shops at the historical sites we visited, whether they were managed by the National Trust, English Heritage, or a more local organizing body. What better way to continue to experience the atmosphere of a historical locale than to read a novel set there?

Here are some examples.

At the Beamish Open Air Museum in County Durham, the shop had numerous copies of Janet MacLeod Trotter's historical sagas set in England's North East. This was a fabulous and large site, with restored buildings dating from the Georgian, Victorian, Edwardian, and WWII eras, as well as costumed interpreters. We spent most of a day wandering around here.

It shouldn't surprise anyone that Bernard Cornwell's Saxon novels about Uhtred of Bebbanburg were in evidence at the shop at Bamburgh Castle.

The shop at Lindisfarne Priory offered a selection of historical novels set in and around monasteries and abbeys, such as Cassandra Clark's medieval mysteries about the Abbess of Meaux. The Holy Island is accessible by causeway only at low tide, which gave us a few hours to explore the area last Monday morning. It's definitely worth a trip.

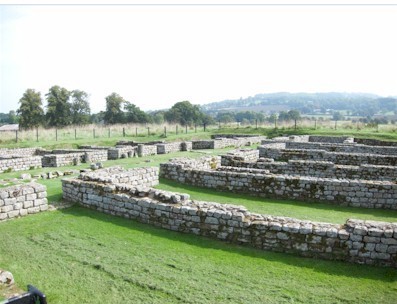

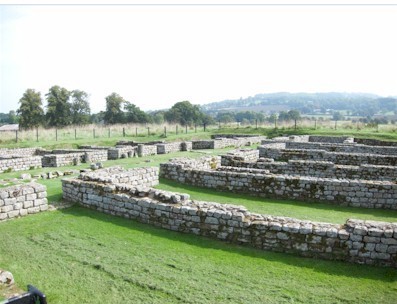

The Chesters Roman Fort and Museum, near Chollerford in Northumberland, hosts the well-preserved ruins of a British Roman cavalry fort; it's located on Hadrian's Wall. The gift shop at this site sold the historical adventure novels of Ben Kane and Simon Scarrow.

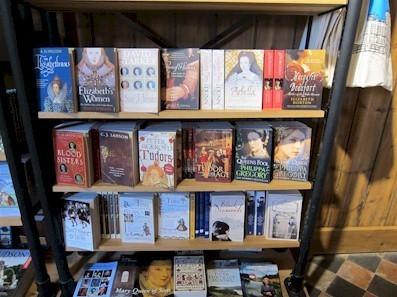

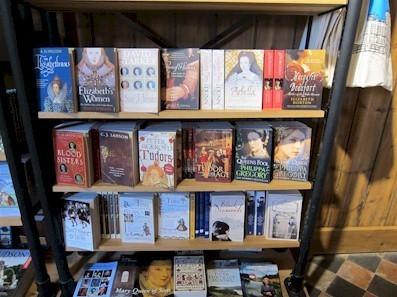

Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire, the grand Elizabethan-era country house commissioned by powerful noblewoman Bess of Hardwick, had a nice array of books in its shop, below, including novels by Philippa Gregory and C.J. Sansom. There was plenty of historical nonfiction about Tudor notables, too.

As a result, many visitors to these historical landmarks will be introduced to historical fiction and popular history. I don't recall seeing this happening to such an extent on my last trip to the UK two years ago. If this is a new trend, I hope it continues.

I found it noteworthy that historical fiction had a presence in most of the gift shops at the historical sites we visited, whether they were managed by the National Trust, English Heritage, or a more local organizing body. What better way to continue to experience the atmosphere of a historical locale than to read a novel set there?

Here are some examples.

At the Beamish Open Air Museum in County Durham, the shop had numerous copies of Janet MacLeod Trotter's historical sagas set in England's North East. This was a fabulous and large site, with restored buildings dating from the Georgian, Victorian, Edwardian, and WWII eras, as well as costumed interpreters. We spent most of a day wandering around here.

It shouldn't surprise anyone that Bernard Cornwell's Saxon novels about Uhtred of Bebbanburg were in evidence at the shop at Bamburgh Castle.

The shop at Lindisfarne Priory offered a selection of historical novels set in and around monasteries and abbeys, such as Cassandra Clark's medieval mysteries about the Abbess of Meaux. The Holy Island is accessible by causeway only at low tide, which gave us a few hours to explore the area last Monday morning. It's definitely worth a trip.

The Chesters Roman Fort and Museum, near Chollerford in Northumberland, hosts the well-preserved ruins of a British Roman cavalry fort; it's located on Hadrian's Wall. The gift shop at this site sold the historical adventure novels of Ben Kane and Simon Scarrow.

Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire, the grand Elizabethan-era country house commissioned by powerful noblewoman Bess of Hardwick, had a nice array of books in its shop, below, including novels by Philippa Gregory and C.J. Sansom. There was plenty of historical nonfiction about Tudor notables, too.

As a result, many visitors to these historical landmarks will be introduced to historical fiction and popular history. I don't recall seeing this happening to such an extent on my last trip to the UK two years ago. If this is a new trend, I hope it continues.

Published on September 14, 2014 12:14

September 11, 2014

Book review: The Secret Life of Violet Grant, by Beatriz Williams

This smashing summer read introduces two ambitious career women living fifty years apart: Violet Schuyler Grant, an American atomic physicist in WWI-era Oxford and Berlin; and her great-niece, Vivian Schuyler, who defies her posh family to work at a magazine in 1960s Manhattan. While Violet’s courage, drive, and vulnerability make her a worthy heroine, Vivian’s cheeky and whip-smart voice steals the show.

The younger Schuyler gets caught up in a tantalizing mystery when a shabby old valise addressed to Violet shows up in her mail. Vivian also finds romance – a complicated one – with “Doctor Paul,” the dreamy surgeon she meets at the post office. Rumored to have murdered her husband and run off with her lover during the Great War, Violet hasn’t been mentioned chez Schuyler for decades, so Vivian is startled to learn of her existence – even more so when she pries the suitcase open and reads what’s inside.

The younger Schuyler gets caught up in a tantalizing mystery when a shabby old valise addressed to Violet shows up in her mail. Vivian also finds romance – a complicated one – with “Doctor Paul,” the dreamy surgeon she meets at the post office. Rumored to have murdered her husband and run off with her lover during the Great War, Violet hasn’t been mentioned chez Schuyler for decades, so Vivian is startled to learn of her existence – even more so when she pries the suitcase open and reads what’s inside.

As Vivian digs into her shadowy relative’s life, with the hopes of writing a dishy story that will be her big break, Violet’s tale of her disastrous marriage and risky affair with her husband’s former student unfolds in parallel. Brilliant but inexperienced with men, Violet is flattered by the attention of her older mentor, Dr. Walter Grant, whom she weds. Her dismay and fear are palpable when she discovers his controlling nature and infidelity.

Williams confidently re-creates both New York in the freewheeling ‘60s and the growing tension of prewar Europe, and she amps up the suspense as Violet’s situation gets desperate. Vivian’s commendable loyalty to her uber-rich friend Gogo adds interest, but the novel’s best part is simply watching the fabulous and always fashionably dressed Vivs in action. By the time she daringly acknowledges the plot’s big coincidence, she already has readers eating out of her hand. It satisfies on many levels, and it’s also immense fun.

The Secret Life of Violet Grant was published in June by Putnam in hardcover (436pp, $26.95 / Can$31.00). This review first appeared in August's Historical Novels Review. I loved the author's first book, Overseas , and thought this one was great as well, though the style is somewhat different.

The younger Schuyler gets caught up in a tantalizing mystery when a shabby old valise addressed to Violet shows up in her mail. Vivian also finds romance – a complicated one – with “Doctor Paul,” the dreamy surgeon she meets at the post office. Rumored to have murdered her husband and run off with her lover during the Great War, Violet hasn’t been mentioned chez Schuyler for decades, so Vivian is startled to learn of her existence – even more so when she pries the suitcase open and reads what’s inside.

The younger Schuyler gets caught up in a tantalizing mystery when a shabby old valise addressed to Violet shows up in her mail. Vivian also finds romance – a complicated one – with “Doctor Paul,” the dreamy surgeon she meets at the post office. Rumored to have murdered her husband and run off with her lover during the Great War, Violet hasn’t been mentioned chez Schuyler for decades, so Vivian is startled to learn of her existence – even more so when she pries the suitcase open and reads what’s inside. As Vivian digs into her shadowy relative’s life, with the hopes of writing a dishy story that will be her big break, Violet’s tale of her disastrous marriage and risky affair with her husband’s former student unfolds in parallel. Brilliant but inexperienced with men, Violet is flattered by the attention of her older mentor, Dr. Walter Grant, whom she weds. Her dismay and fear are palpable when she discovers his controlling nature and infidelity.

Williams confidently re-creates both New York in the freewheeling ‘60s and the growing tension of prewar Europe, and she amps up the suspense as Violet’s situation gets desperate. Vivian’s commendable loyalty to her uber-rich friend Gogo adds interest, but the novel’s best part is simply watching the fabulous and always fashionably dressed Vivs in action. By the time she daringly acknowledges the plot’s big coincidence, she already has readers eating out of her hand. It satisfies on many levels, and it’s also immense fun.

The Secret Life of Violet Grant was published in June by Putnam in hardcover (436pp, $26.95 / Can$31.00). This review first appeared in August's Historical Novels Review. I loved the author's first book, Overseas , and thought this one was great as well, though the style is somewhat different.

Published on September 11, 2014 08:00

September 7, 2014

Metifs, Meameloucs, Railway Cars, and The Cottoncrest Curse: An essay by Michael H. Rubin

Lawyer, professor, musician, speaker, and now debut novelist Michael H. Rubin is here with an original essay about the implications of the Plessy v. Ferguson decision by the U.S. Supreme Court and the role it plays in his new The Cottoncrest Curse, a legal thriller that intertwines fictional and historical characters. ~

Metifs, Meameloucs, Railway Cars,

and The Cottoncrest Curse

By Michael H. Rubin

In The Cottoncrest Curse, a series of gruesome deaths ignite feuds that burn a path from the cotton fields to the courthouse steps, from the moss-draped bayous of Cajun country to the bordellos of 19th-century New Orleans, from the Civil War era to the Civil Rights era and across the Jim Crow decades to the Freedom Marches of the 1960s.

At the heart of the story is the apparent suicide of an elderly Confederate Colonel who, two decades after the end of the Civil War, viciously slit the throat of his beautiful young wife and then fatally shot himself. But his death was not the first suicide of an owner of the Cottoncrest Plantation, and it was not to be the last…Or was this a double homicide, and are the deaths of the plantation’s owners across the decades linked? Suspicion for the murder of the colonel and his wife falls upon Jake Gold, an itinerant peddler who trades razor-sharp knives for local furs and who has many deep secrets to conceal.

At the heart of the story is the apparent suicide of an elderly Confederate Colonel who, two decades after the end of the Civil War, viciously slit the throat of his beautiful young wife and then fatally shot himself. But his death was not the first suicide of an owner of the Cottoncrest Plantation, and it was not to be the last…Or was this a double homicide, and are the deaths of the plantation’s owners across the decades linked? Suspicion for the murder of the colonel and his wife falls upon Jake Gold, an itinerant peddler who trades razor-sharp knives for local furs and who has many deep secrets to conceal.

So, what are metifs and meamaloucs, and how are they and railway cars involved in The Cottoncrest Curse?

The Cottoncrest Curse explores the dangers inherent in preconceived stereotypes. The infamous Jim Crow laws, which propel the action in The Cottoncrest Curse, were built on the fallacious stereotype that blacks were inherently inferior to whites. The Jim Crow laws were given validity by the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Plessy v. Ferguson, the separate-but-equal case. Plessy arose, however, not as a way to oppress blacks but rather as a test case to vindicate their rights, and a number of characters in The Cottoncrest Curse are involved in the Plessy case.

Jim Crow laws resulted in legalized discrimination against blacks. These laws didn’t merely mandate segregation and unequal treatment of those who “appeared” to be “black.” They attempted to parse bloodlines, so that even if one’s parents and grandparents were “white,” an individual was still considered “black” because of his or her distant ancestors. Louisiana even had terms to describe these bloodlines. Discrimination was legal against “metifs” — those who had just one black great-grandparent — or even “meameloucs” — those with just one black great-great grandparent.

Louis Martinet, a black lawyer who lived in the late 1800s and who appears in The Cottoncrest Curse, came up with a brilliant idea. The Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution outlawed slavery, and the Fourteenth Amendment prohibited states from making or enforcing any laws that would “abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.” Yet, Louisiana had passed a law prohibiting blacks and whites from sitting in the same railway cars, relegating blacks to separate cars.

Martinet believed that separate was inherently unequal, and so he recruited Homer Plessy to be a plaintiff. Both Martinet and Plessy were light-skinned; in fact, both could passe blanc — pass for white — if they wanted to, but neither did. Both were proud of their black heritage.

Homer Plessy boarded a railway train in New Orleans bound for the Louisiana town of Covington and deliberately sat in the “white” car. When the conductor came to take his ticket, Homer did not merely hand it to him and attempt to passe blanc. Rather, Homer, who was a metif, boldly spoke up, declaring that he was “a Negro.” He was promptly arrested, as Homer and Martinet had anticipated, and the case challenging the mandatory separation of whites and blacks was underway.

The result, however, was not what Homer Plessy, Louis Martinet, and a host of others had hoped it would be. The Louisiana Supreme Court upheld the statute, recognizing that to strike it down would undermine all the Jim Crow laws, and the United States Supreme Court affirmed the ruling with its infamous “separate but equal” pronouncement. It was not until 1954, when Brown v. Board of Education was decided, that Plessy was overturned by Brown’s famous statement that separate is inherently unequal.

While Jake Gold, the protagonist in The Cottoncrest Curse, is fictional, many historical figures — like Louis Martinet and Homer Plessy — are key to the plot. I wanted to create a page-turning thriller that was firmly grounded in historical events, and I’m pleased by the reception it has received so far, with Publishers Weekly calling it a “gripping debut mystery” and James Carville deeming it a “powerful epic” that is “expertly composed in both its historical content and beautifully constructed scenery.”

I hope readers will enjoy reading The Cottoncrest Curse as much as I enjoyed doing the historical research and writing the novel.

About Michael H. Rubin

Michael H. Rubin has conquered many worlds, and now he is branching out into new territory – fiction.

Rubin is a former professional jazz pianist and composer who has played in the New Orleans French Quarter and a former television and radio host. He is an accomplished lawyer who helps manage a law firm that has offices stretching from California to Florida and from Texas and Louisiana to New York.

Rubin is a former professional jazz pianist and composer who has played in the New Orleans French Quarter and a former television and radio host. He is an accomplished lawyer who helps manage a law firm that has offices stretching from California to Florida and from Texas and Louisiana to New York.

He has served as an adjunct law professor at the Louisiana State University Law School for more than 30 years, and is a nationally known speaker whose talks on topics such as legal ethics, negotiations, appellate advocacy, real estate, finance and trial tactics have been widely praised throughout the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom.

Rubin has presented more than 375 major lectures and papers. He is an author, co-author, and contributing writer of 13 legal books and more than 30 articles for law reviews and periodicals, and his writings have been cited as authoritative by state and federal courts, including state supreme courts and federal appellate courts.

His latest legal book is Louisiana Security Devices: A Précis (Lexis/Nexis 2011), and his first novel, The Cottoncrest Curse is a legal thriller and multi-generational saga to be published September 10, 2014 by the award-winning LSU Press. The novel will be available nationwide in bookstores and as an e-book.

Metifs, Meameloucs, Railway Cars,

and The Cottoncrest Curse

By Michael H. Rubin

In The Cottoncrest Curse, a series of gruesome deaths ignite feuds that burn a path from the cotton fields to the courthouse steps, from the moss-draped bayous of Cajun country to the bordellos of 19th-century New Orleans, from the Civil War era to the Civil Rights era and across the Jim Crow decades to the Freedom Marches of the 1960s.

At the heart of the story is the apparent suicide of an elderly Confederate Colonel who, two decades after the end of the Civil War, viciously slit the throat of his beautiful young wife and then fatally shot himself. But his death was not the first suicide of an owner of the Cottoncrest Plantation, and it was not to be the last…Or was this a double homicide, and are the deaths of the plantation’s owners across the decades linked? Suspicion for the murder of the colonel and his wife falls upon Jake Gold, an itinerant peddler who trades razor-sharp knives for local furs and who has many deep secrets to conceal.

At the heart of the story is the apparent suicide of an elderly Confederate Colonel who, two decades after the end of the Civil War, viciously slit the throat of his beautiful young wife and then fatally shot himself. But his death was not the first suicide of an owner of the Cottoncrest Plantation, and it was not to be the last…Or was this a double homicide, and are the deaths of the plantation’s owners across the decades linked? Suspicion for the murder of the colonel and his wife falls upon Jake Gold, an itinerant peddler who trades razor-sharp knives for local furs and who has many deep secrets to conceal. So, what are metifs and meamaloucs, and how are they and railway cars involved in The Cottoncrest Curse?

The Cottoncrest Curse explores the dangers inherent in preconceived stereotypes. The infamous Jim Crow laws, which propel the action in The Cottoncrest Curse, were built on the fallacious stereotype that blacks were inherently inferior to whites. The Jim Crow laws were given validity by the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Plessy v. Ferguson, the separate-but-equal case. Plessy arose, however, not as a way to oppress blacks but rather as a test case to vindicate their rights, and a number of characters in The Cottoncrest Curse are involved in the Plessy case.

Jim Crow laws resulted in legalized discrimination against blacks. These laws didn’t merely mandate segregation and unequal treatment of those who “appeared” to be “black.” They attempted to parse bloodlines, so that even if one’s parents and grandparents were “white,” an individual was still considered “black” because of his or her distant ancestors. Louisiana even had terms to describe these bloodlines. Discrimination was legal against “metifs” — those who had just one black great-grandparent — or even “meameloucs” — those with just one black great-great grandparent.

Louis Martinet, a black lawyer who lived in the late 1800s and who appears in The Cottoncrest Curse, came up with a brilliant idea. The Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution outlawed slavery, and the Fourteenth Amendment prohibited states from making or enforcing any laws that would “abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.” Yet, Louisiana had passed a law prohibiting blacks and whites from sitting in the same railway cars, relegating blacks to separate cars.

Martinet believed that separate was inherently unequal, and so he recruited Homer Plessy to be a plaintiff. Both Martinet and Plessy were light-skinned; in fact, both could passe blanc — pass for white — if they wanted to, but neither did. Both were proud of their black heritage.

Homer Plessy boarded a railway train in New Orleans bound for the Louisiana town of Covington and deliberately sat in the “white” car. When the conductor came to take his ticket, Homer did not merely hand it to him and attempt to passe blanc. Rather, Homer, who was a metif, boldly spoke up, declaring that he was “a Negro.” He was promptly arrested, as Homer and Martinet had anticipated, and the case challenging the mandatory separation of whites and blacks was underway.

The result, however, was not what Homer Plessy, Louis Martinet, and a host of others had hoped it would be. The Louisiana Supreme Court upheld the statute, recognizing that to strike it down would undermine all the Jim Crow laws, and the United States Supreme Court affirmed the ruling with its infamous “separate but equal” pronouncement. It was not until 1954, when Brown v. Board of Education was decided, that Plessy was overturned by Brown’s famous statement that separate is inherently unequal.

While Jake Gold, the protagonist in The Cottoncrest Curse, is fictional, many historical figures — like Louis Martinet and Homer Plessy — are key to the plot. I wanted to create a page-turning thriller that was firmly grounded in historical events, and I’m pleased by the reception it has received so far, with Publishers Weekly calling it a “gripping debut mystery” and James Carville deeming it a “powerful epic” that is “expertly composed in both its historical content and beautifully constructed scenery.”

I hope readers will enjoy reading The Cottoncrest Curse as much as I enjoyed doing the historical research and writing the novel.

About Michael H. Rubin

Michael H. Rubin has conquered many worlds, and now he is branching out into new territory – fiction.

Rubin is a former professional jazz pianist and composer who has played in the New Orleans French Quarter and a former television and radio host. He is an accomplished lawyer who helps manage a law firm that has offices stretching from California to Florida and from Texas and Louisiana to New York.

Rubin is a former professional jazz pianist and composer who has played in the New Orleans French Quarter and a former television and radio host. He is an accomplished lawyer who helps manage a law firm that has offices stretching from California to Florida and from Texas and Louisiana to New York. He has served as an adjunct law professor at the Louisiana State University Law School for more than 30 years, and is a nationally known speaker whose talks on topics such as legal ethics, negotiations, appellate advocacy, real estate, finance and trial tactics have been widely praised throughout the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom.

Rubin has presented more than 375 major lectures and papers. He is an author, co-author, and contributing writer of 13 legal books and more than 30 articles for law reviews and periodicals, and his writings have been cited as authoritative by state and federal courts, including state supreme courts and federal appellate courts.

His latest legal book is Louisiana Security Devices: A Précis (Lexis/Nexis 2011), and his first novel, The Cottoncrest Curse is a legal thriller and multi-generational saga to be published September 10, 2014 by the award-winning LSU Press. The novel will be available nationwide in bookstores and as an e-book.

Published on September 07, 2014 22:00

September 4, 2014

A short review: Neverhome, by Laird Hunt

Although historical novelists have been slow to honor the brave women who fought in America’s wars disguised as men, several, including Erin Lindsay McCabe and Alex Myers, have recently remedied this oversight. Hunt joins their strong ranks with an enthralling novel about an Indiana farm wife who leaves her husband in 1862 to become a Union soldier; she has her own reasons why.

Although historical novelists have been slow to honor the brave women who fought in America’s wars disguised as men, several, including Erin Lindsay McCabe and Alex Myers, have recently remedied this oversight. Hunt joins their strong ranks with an enthralling novel about an Indiana farm wife who leaves her husband in 1862 to become a Union soldier; she has her own reasons why.Don’t expect instructive details on how “Ash Thompson” pulls off this masquerade. Instead, Hunt’s is an exquisitely wrought vision of the terrible ravages of war—on the land, on the human body, and on the mind—as encountered by a tough, clever woman.

As she marches from camp and into battle, into unfamiliar Southern towns and across woodland filled with intermingled blue and gray dead, she bests others and is herself bested. Her journey’s every step is finely rendered in an authentic rural dialect. Readers will encounter eye-opening surprises in both her future and progressively revealed past while avidly living each moment alongside her, marveling at her determination and amazing courage.

Neverhome will be published by Little, Brown on September 7th in hardcover (256pp, $26.95). This review first appeared in Booklist's September 1st issue. Looking for subject-based "readalikes" for Neverhome? I've listed some in my post from this past Friday. There's plenty of action in this novel, though it also falls within the realm of literary fiction, so fans of Cold Mountain and its ilk should find it of interest as well.

Published on September 04, 2014 22:00

September 1, 2014

Historical fiction vs. historical fantasy: Which is it? A guest post by Maggie Anton

Maggie Anton's guest post today is perfect for readers like me who enjoy learning about trends in historical fiction and seeing where subgroups within the genre meet and overlap. Here she discusses the fluid borders between historical fiction and historical fantasy, and how the novels in her Rav Hisda's Daughter duo might possibly be categorized. Book 1: Apprentice and Book 2: Enchantress both take place in a fascinating but underutilized historical setting, 4th-century Babylonia, and cover a vital period in Jewish history. Welcome, Maggie!

~

Historical Fiction vs. Historical Fantasy: Which Is It?

Maggie Anton

I’ve noticed a debate in online historical fiction groups about the difference between a historical novel and a historical fantasy. On first glance, the difference is clear. A historical novel is set during a historical period on Earth, with real historical details as to politics (names of rulers), technology levels, and clothing styles. Definitive examples include Hilary Mantel’s Bring Up the Bodies and Gore Vidal’s Lincoln. Even novels such as Gone with the Wind, where the characters didn't exist and there is no proof that the plotline really happened, are considered historical fiction. However adding an element that could not happen in the real world – such as vampires, dragons, ghosts, or sorcery – makes it historical fantasy as long as the action takes place on Earth. Recent popular examples include Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell by Susanna Clarke and The Golem and the Jinni by Helene Wecker. But I don’t think these genres are quite so clear-cut. During most of human history, everyone believed in things that we moderns say do not exist, just as things exist today that our ancestors would consider magic.

What happens when a novelist living during those olden days writes about earlier times? I doubt Thomas Malory considered his Le Morte d’Arthur a fantasy, nor did Homer when writing The Odyssey. The earliest historical fiction included ghost stories and fairy tales, which nobody separated from legends that did not depend upon the supernatural. Stories set in ancient China often included dragons as characters, the assumption being that these great beasts either died out or are in hiding.

What happens when a novelist living during those olden days writes about earlier times? I doubt Thomas Malory considered his Le Morte d’Arthur a fantasy, nor did Homer when writing The Odyssey. The earliest historical fiction included ghost stories and fairy tales, which nobody separated from legends that did not depend upon the supernatural. Stories set in ancient China often included dragons as characters, the assumption being that these great beasts either died out or are in hiding.

How about when a modern novelist tackles these ancient days of yore? When does a historical novel become a historical fantasy? In my Rashi’s Daughters trilogy, which takes place in medieval France, characters accept that illness came from foul air or bad food, but might also be the result of demon attacks or divine punishment. Precautions against these include actions we would call superstitions, such as wearing amulets or avoiding certain activities on “unlucky” days. I detailed many of these “magical” practices, but left it up to the reader whether they actually worked. As far as I was concerned, I was writing historical fiction authentic for its time period.

My Rav Hisda’s Daughter duo, Apprentice and Enchantress, takes place in 4th-century Babylonia, where no one doubted that "magic" was real (the word “magic” comes from Magi, Zoroastrian priests who were part of the ruling Persian hierarchy). Most of my characters are members of the community of rabbis who created the Talmud, the text that has been the source of Jewish law and tradition for 1500 years. But the Talmud is more than a corpus of complicated legal arguments. Tales abound of rabbis, and sorceresses, who perform actual magic.

I wrote both books from the heroine’s first person POV, which meant that I, the purported author, believed just like everyone else that misfortunes such as disease, miscarriage and premature death were caused by demons, sorcerers’ curses, and the Evil Eye. She/I also believed that these problems could be cured or prevented by spells inscribed by skilled healers on amulets and incantation bowls.

In Apprentice, my heroine trains to become one of these healers. All the incantations I include are authentic, that is from archaeological evidence and ancient magic manuals. Some are found in the Talmud itself. Though the techniques she learns would certainly be considered magic today, I tried to stay on the historical fiction side rather than cross into fantasy. My heroine sensed, not saw, the angels who made her incantations work. When her father cast a spell to control the wind, the wind might have changed direction on its own rather than him having caused it to do so. When she suffers a near-fatal illness, she dreams of the hero’s battling the Angel of Death to save her.

With Enchantress, rather than pussyfooting at the border, I charged fully into fantasy. My hero consults with ghosts, creates a golem, and resurrects another rabbi – all as described in the Talmud. My heroine conjures Ashmedai the Demon King, uses a magic ring to speak with animals, and creates food from nothing – again, magic described in the Talmud.

With Enchantress, rather than pussyfooting at the border, I charged fully into fantasy. My hero consults with ghosts, creates a golem, and resurrects another rabbi – all as described in the Talmud. My heroine conjures Ashmedai the Demon King, uses a magic ring to speak with animals, and creates food from nothing – again, magic described in the Talmud.

So it would appear that my novel is a historical fantasy. Except that my characters are pious historical figures whose actions are documented in religious texts. How do we classify historical novels with saints or Biblical figures who perform miracles? One person's miracle can be seen as magic by someone else. What about divine, or angelic, intervention?

Here’s another thing to ponder. The very definition of magic assumes that it doesn’t work, but the kind of healing magic that Rav Hisda’s daughter and her enchantress colleagues practiced may very well have worked. We know today that the placebo effect is real, even when the patient knows it’s a placebo. So casting a spell that calls upon angels to force the demons afflicting a person to flee might indeed make the person better. The same for chanting psalms in the sickroom.

In fact, one of her “magic” procedures, that of saying an incantation while washing one’s hands three times to protect against demons in the privy, would certainly work. Substitute “bacteria and viruses” for “demons” and you have one of the best prophylactic practices in modern medicine.

These days we agree that vampires, golems and jinn do not exist except in the realm of fantasy. But over 75% of Americans believe in angels and many people have sensed the spirit of a recently deceased loved one. And whether sorcery exists depends on how you define it. Personally, I think microwaves and wireless Internet are pretty magical.

Hopefully everyone understands the difference between Lincoln and Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter, but even reviewers may not agree about novels at the fuzzy border where something supernatural makes an appearance. That leaves it up to readers to learn more about the plot and decide for themselves if a particular book might be one they’d enjoy – exactly as they did before this dichotomy.

Which is one of the reasons websites such as Reading the Past are necessary.

~

Maggie Anton was born Margaret Antonofsky in Los Angeles, California, where she still resides. Raised in a secular, socialist household, she reached adulthood with little knowledge of her Jewish religion. In 1992 Anton joined a women's Talmud class taught by Rachel Adler, now a professor at Hebrew Union College in Los Angeles. To her surprise, she fell in love with Talmud, a passion that has continued unabated for twenty years. Intrigued that the great Talmudic scholar Rashi had no sons, only daughters, Anton researched the family and decided to write novels about them. Thus the award-winning trilogy, Rashi's Daughters, was born, to be followed by National Jewish Book Award finalist, Rav Hisda's Daughter: Apprentice. Still studying women and Talmud, Anton has lectured throughout North America and Israel about the history behind her novels. You can follow her blog and contact her at her website, http://www.maggieanton.com.

Maggie Anton was born Margaret Antonofsky in Los Angeles, California, where she still resides. Raised in a secular, socialist household, she reached adulthood with little knowledge of her Jewish religion. In 1992 Anton joined a women's Talmud class taught by Rachel Adler, now a professor at Hebrew Union College in Los Angeles. To her surprise, she fell in love with Talmud, a passion that has continued unabated for twenty years. Intrigued that the great Talmudic scholar Rashi had no sons, only daughters, Anton researched the family and decided to write novels about them. Thus the award-winning trilogy, Rashi's Daughters, was born, to be followed by National Jewish Book Award finalist, Rav Hisda's Daughter: Apprentice. Still studying women and Talmud, Anton has lectured throughout North America and Israel about the history behind her novels. You can follow her blog and contact her at her website, http://www.maggieanton.com.

~

Historical Fiction vs. Historical Fantasy: Which Is It?

Maggie Anton

I’ve noticed a debate in online historical fiction groups about the difference between a historical novel and a historical fantasy. On first glance, the difference is clear. A historical novel is set during a historical period on Earth, with real historical details as to politics (names of rulers), technology levels, and clothing styles. Definitive examples include Hilary Mantel’s Bring Up the Bodies and Gore Vidal’s Lincoln. Even novels such as Gone with the Wind, where the characters didn't exist and there is no proof that the plotline really happened, are considered historical fiction. However adding an element that could not happen in the real world – such as vampires, dragons, ghosts, or sorcery – makes it historical fantasy as long as the action takes place on Earth. Recent popular examples include Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell by Susanna Clarke and The Golem and the Jinni by Helene Wecker. But I don’t think these genres are quite so clear-cut. During most of human history, everyone believed in things that we moderns say do not exist, just as things exist today that our ancestors would consider magic.

What happens when a novelist living during those olden days writes about earlier times? I doubt Thomas Malory considered his Le Morte d’Arthur a fantasy, nor did Homer when writing The Odyssey. The earliest historical fiction included ghost stories and fairy tales, which nobody separated from legends that did not depend upon the supernatural. Stories set in ancient China often included dragons as characters, the assumption being that these great beasts either died out or are in hiding.

What happens when a novelist living during those olden days writes about earlier times? I doubt Thomas Malory considered his Le Morte d’Arthur a fantasy, nor did Homer when writing The Odyssey. The earliest historical fiction included ghost stories and fairy tales, which nobody separated from legends that did not depend upon the supernatural. Stories set in ancient China often included dragons as characters, the assumption being that these great beasts either died out or are in hiding.How about when a modern novelist tackles these ancient days of yore? When does a historical novel become a historical fantasy? In my Rashi’s Daughters trilogy, which takes place in medieval France, characters accept that illness came from foul air or bad food, but might also be the result of demon attacks or divine punishment. Precautions against these include actions we would call superstitions, such as wearing amulets or avoiding certain activities on “unlucky” days. I detailed many of these “magical” practices, but left it up to the reader whether they actually worked. As far as I was concerned, I was writing historical fiction authentic for its time period.

My Rav Hisda’s Daughter duo, Apprentice and Enchantress, takes place in 4th-century Babylonia, where no one doubted that "magic" was real (the word “magic” comes from Magi, Zoroastrian priests who were part of the ruling Persian hierarchy). Most of my characters are members of the community of rabbis who created the Talmud, the text that has been the source of Jewish law and tradition for 1500 years. But the Talmud is more than a corpus of complicated legal arguments. Tales abound of rabbis, and sorceresses, who perform actual magic.

I wrote both books from the heroine’s first person POV, which meant that I, the purported author, believed just like everyone else that misfortunes such as disease, miscarriage and premature death were caused by demons, sorcerers’ curses, and the Evil Eye. She/I also believed that these problems could be cured or prevented by spells inscribed by skilled healers on amulets and incantation bowls.

In Apprentice, my heroine trains to become one of these healers. All the incantations I include are authentic, that is from archaeological evidence and ancient magic manuals. Some are found in the Talmud itself. Though the techniques she learns would certainly be considered magic today, I tried to stay on the historical fiction side rather than cross into fantasy. My heroine sensed, not saw, the angels who made her incantations work. When her father cast a spell to control the wind, the wind might have changed direction on its own rather than him having caused it to do so. When she suffers a near-fatal illness, she dreams of the hero’s battling the Angel of Death to save her.

With Enchantress, rather than pussyfooting at the border, I charged fully into fantasy. My hero consults with ghosts, creates a golem, and resurrects another rabbi – all as described in the Talmud. My heroine conjures Ashmedai the Demon King, uses a magic ring to speak with animals, and creates food from nothing – again, magic described in the Talmud.

With Enchantress, rather than pussyfooting at the border, I charged fully into fantasy. My hero consults with ghosts, creates a golem, and resurrects another rabbi – all as described in the Talmud. My heroine conjures Ashmedai the Demon King, uses a magic ring to speak with animals, and creates food from nothing – again, magic described in the Talmud.So it would appear that my novel is a historical fantasy. Except that my characters are pious historical figures whose actions are documented in religious texts. How do we classify historical novels with saints or Biblical figures who perform miracles? One person's miracle can be seen as magic by someone else. What about divine, or angelic, intervention?

Here’s another thing to ponder. The very definition of magic assumes that it doesn’t work, but the kind of healing magic that Rav Hisda’s daughter and her enchantress colleagues practiced may very well have worked. We know today that the placebo effect is real, even when the patient knows it’s a placebo. So casting a spell that calls upon angels to force the demons afflicting a person to flee might indeed make the person better. The same for chanting psalms in the sickroom.

In fact, one of her “magic” procedures, that of saying an incantation while washing one’s hands three times to protect against demons in the privy, would certainly work. Substitute “bacteria and viruses” for “demons” and you have one of the best prophylactic practices in modern medicine.

These days we agree that vampires, golems and jinn do not exist except in the realm of fantasy. But over 75% of Americans believe in angels and many people have sensed the spirit of a recently deceased loved one. And whether sorcery exists depends on how you define it. Personally, I think microwaves and wireless Internet are pretty magical.

Hopefully everyone understands the difference between Lincoln and Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter, but even reviewers may not agree about novels at the fuzzy border where something supernatural makes an appearance. That leaves it up to readers to learn more about the plot and decide for themselves if a particular book might be one they’d enjoy – exactly as they did before this dichotomy.

Which is one of the reasons websites such as Reading the Past are necessary.

~

Maggie Anton was born Margaret Antonofsky in Los Angeles, California, where she still resides. Raised in a secular, socialist household, she reached adulthood with little knowledge of her Jewish religion. In 1992 Anton joined a women's Talmud class taught by Rachel Adler, now a professor at Hebrew Union College in Los Angeles. To her surprise, she fell in love with Talmud, a passion that has continued unabated for twenty years. Intrigued that the great Talmudic scholar Rashi had no sons, only daughters, Anton researched the family and decided to write novels about them. Thus the award-winning trilogy, Rashi's Daughters, was born, to be followed by National Jewish Book Award finalist, Rav Hisda's Daughter: Apprentice. Still studying women and Talmud, Anton has lectured throughout North America and Israel about the history behind her novels. You can follow her blog and contact her at her website, http://www.maggieanton.com.

Maggie Anton was born Margaret Antonofsky in Los Angeles, California, where she still resides. Raised in a secular, socialist household, she reached adulthood with little knowledge of her Jewish religion. In 1992 Anton joined a women's Talmud class taught by Rachel Adler, now a professor at Hebrew Union College in Los Angeles. To her surprise, she fell in love with Talmud, a passion that has continued unabated for twenty years. Intrigued that the great Talmudic scholar Rashi had no sons, only daughters, Anton researched the family and decided to write novels about them. Thus the award-winning trilogy, Rashi's Daughters, was born, to be followed by National Jewish Book Award finalist, Rav Hisda's Daughter: Apprentice. Still studying women and Talmud, Anton has lectured throughout North America and Israel about the history behind her novels. You can follow her blog and contact her at her website, http://www.maggieanton.com.

Published on September 01, 2014 22:00

August 29, 2014

They dressed as men and went to war

We've been seeing many new historical novels about brave women who went to war in male disguise. All six of the novels below have publication dates in 2014 or 2015, and I can't think of a single event or benchmark title that got this mini-trend rolling, other than maybe an increased interest in women's history in general. I've also been pondering earlier novels that fit this category and haven't come up with much, other than Sharyn McCrumb's 2003 release Ghost Riders, which had Civil War soldier Malinda Blalock (a historical figure) as a character. Can you think of others?

These novels aren't fanciful in premise. In actuality, there were many women who disguised their sex and fought in the US Civil War and in earlier battles, but recognition of and pride in their accomplishments has often been long in coming. These works of fiction, some of which are based on the lives of specific historical women, help to spread word about their deeds and heroism in the popular consciousness.

A young woman who had been fighting for the Union in disguise has to hide her loyalties after she's wounded and gets trapped behind Confederate lines. RiverNorth, June 2014.

A rare novel that looks at this scenario from the Confederate side, as two Southern sisters enlist in the Confederate army as new recruits, their secret known only to one another. The so-authors are sisters as well. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, March 2015.

Her husband being too weak to go to war, an Indiana farm wife dons male garb and marches off to fight for the Union. I'll have a review of this new literary novel shortly. Little Brown, September 2014.

Believing her place is with her newly-wed husband, Rosetta Wakefield secretly follows him into the Union ranks, fighting alongside him and proving her worth in battle. Loosely based on the life of Sarah Rosetta Wakeman. Crown, January 2014; out in paperback in September, with a beautiful new cover.

This novel about Massachusetts heroine Deborah Sampson shows her external and internal transformations during her service in the Revolutionary War. See my review of Revolutionary as well as

From the author of the 4-book Far Western Civil War series comes a new novel about Emma Edmonds, who signed on with the 2nd Michigan Volunteers under the name Frank Thompson. BookView Cafe, April 2014.

These novels aren't fanciful in premise. In actuality, there were many women who disguised their sex and fought in the US Civil War and in earlier battles, but recognition of and pride in their accomplishments has often been long in coming. These works of fiction, some of which are based on the lives of specific historical women, help to spread word about their deeds and heroism in the popular consciousness.

A young woman who had been fighting for the Union in disguise has to hide her loyalties after she's wounded and gets trapped behind Confederate lines. RiverNorth, June 2014.

A rare novel that looks at this scenario from the Confederate side, as two Southern sisters enlist in the Confederate army as new recruits, their secret known only to one another. The so-authors are sisters as well. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, March 2015.

Her husband being too weak to go to war, an Indiana farm wife dons male garb and marches off to fight for the Union. I'll have a review of this new literary novel shortly. Little Brown, September 2014.

Believing her place is with her newly-wed husband, Rosetta Wakefield secretly follows him into the Union ranks, fighting alongside him and proving her worth in battle. Loosely based on the life of Sarah Rosetta Wakeman. Crown, January 2014; out in paperback in September, with a beautiful new cover.

This novel about Massachusetts heroine Deborah Sampson shows her external and internal transformations during her service in the Revolutionary War. See my review of Revolutionary as well as

From the author of the 4-book Far Western Civil War series comes a new novel about Emma Edmonds, who signed on with the 2nd Michigan Volunteers under the name Frank Thompson. BookView Cafe, April 2014.

Published on August 29, 2014 08:00

August 27, 2014

Venturing into teen historical fiction: A guest essay by Deborah Swift

I'm glad to welcome Deborah Swift to my site today for a guest post. I've positively reviewed three of her earlier novels here: The Lady's Slipper,

The Gilded Lily

, and

A Divided Inheritance

, all set in the 17th century. With her latest release, she stays in the same time frame but has moved over to the Young Adult arena, although I'm told adult readers will enjoy Shadow on the Highway too. I've already bought my copy and look forward to reading it. In the following essay, she explores the adjustments that were needed to gear her writing to a teen audience.

~

Venturing into Teen Historical Fiction

Deborah Swift

I’ve been writing novels set in the seventeenth century for adults for quite a few years. During my research, I’ve often come across young women aged between fourteen and eighteen, and yet expected to run a household, accept adult responsibilities, marry and bear children. That was the way of life back then. When writing for adults, these heroines of 14 or 15 years of age seem unlikely – far too young to have such maturity. Yet for today’s teen readers of that age, the same characters can appear too mature, too ensconced in an adult life.

As Eliza Graham points out in her excellent article on Historical Fiction Connection, teenagers were not a separate group with their own rules and identity until the twentieth century.

As Eliza Graham points out in her excellent article on Historical Fiction Connection, teenagers were not a separate group with their own rules and identity until the twentieth century.

I pondered on this on and off, as I’m sure it is a problem many historical fiction writers have grappled with, but I came to no definitive answer. Usually, if the character is too young to be behaving in a certain way by our modern standards, I’ll try not to mention her age in years, but just refer to her as ‘young’, for example. Or better, try to make sure the milieu in which she lives, supports and describes such a maturity.

When I came across the history of Lady Katherine Fanshawe – married at fourteen, and a highwaywoman (if we believe the legend) by eighteen, I was attracted to the story, but unsure exactly who would read it. The theme sounded as though it might be attractive to teenagers so I thought I would try writing for a younger age-group. I looked in my local bookshops for examples of historical fiction designed for readers 14 plus, and could find very few. This year at least, readers of that age, according to the bookstore owner, want fantasy and sorcery. To my relief, my local library (hooray!) yielded a much better and more varied stock, and I was able to plunge in, and try to see what creating a younger ‘voice’ might mean for me as a writer. Teen readers, like adult readers, I’m sure are of all different tastes.

What was immediately apparent was that the tone would have to be different from my adult novels. To create a younger voice, my characters would need to be more vibrant, less world-weary and more impetuous. Old-fashioned language would need to be replaced with something more direct. Shadow on the Highway feels more ‘modern’ than my other books, not least in the fact I had to find creative ways to reproduce seventeenth century versions of ‘OMG!’ I hope I have still kept some period authenticity. Immersing myself in the idealism of young people in the 17th century, led me to the Diggers – an early example of an alternative lifestyle, and one I thought might resonate with ecologically aware young readers today. (Read more about them here.)

An added difficulty for me was that the book would need to be shorter – it would be a rare teen that made it to the end of one of my other 500 page books (though I’m sure there are exceptions, including most of us writers when we were younger)! Fortunately the historical material neatly divides into three sections, and there are three main characters, so I thought the story might work as a trilogy. But a trilogy has its own three act structure, and the first book is necessarily quieter, building the bedrock for the rest of the action. With this in mind, the risk is, that if nobody enjoys the first book, it might founder at first base, and then I’d feel awkward spending time writing two more that nobody wants!

Books where I admired the creation of the teenage voice were Phillip Pullman’s Ruby in the Smoke, where the voice was lively and opinionated, something I wanted for my character Lady Katherine. I very much admired Code Name Verity, by Elizabeth Wein, but was aware that my book was not going to be quite so literary and was set a lot further in the past. I turned to Cassandra Clare’s books such as The Clockwork Princess, which had the right tone, but these books veer away from a purely historical setting with their steampunk approach. Here are some other authors with historical settings I enjoyed: Brian Jacques, Eva Ibbotson, Victoria Lamb, Celia Rees, Ann Turnbull, Anna Godbersen amongst others. If I was to highlight one I particularly liked, I would go for The Madman’s Daughter by Megan Shepherd, which had an outstanding sense of time and place.

Writing historical fiction for teens is every bit as demanding as writing for adults, more so, as my teen beta readers were frighteningly direct in their assessment. Some quite frankly didn’t like it. Some got bored. An immense amount of world-building has to go on in the head of the reader for historical fiction to work, and not all readers have a mental image bank yet that they can draw on to help them create the scene in their heads. But when you get a great response it is equally direct – and immensely rewarding. Especially when you have introduced them to a whole new genre of reading. I hope many adults will try some of these books too, after all, as Veronica Roth, author of the Divergent trilogy says, “I think everyone’s got a little teenager inside of them still, and you just have to work to help yourself access that teenager.”

~

Deborah Swift used to work in the theatre and at the BBC as a set and costume designer, before studying for an MA in Creative Writing in 2007. She lives in a beautiful area of Lancashire near the Lake District National Park. She is the author of The Lady’s Slipper and is a member of the Historical Writers Association, the Historical Novel Society, and the Romantic Novelists Association.

Deborah Swift used to work in the theatre and at the BBC as a set and costume designer, before studying for an MA in Creative Writing in 2007. She lives in a beautiful area of Lancashire near the Lake District National Park. She is the author of The Lady’s Slipper and is a member of the Historical Writers Association, the Historical Novel Society, and the Romantic Novelists Association.

For more information, please visit Deborah’s website. You can also find her on Facebook and Twitter.

Shadow on the Highway was published in July in paperback and as an ebook (see Amazon UK or Amazon US).

~

Venturing into Teen Historical Fiction

Deborah Swift

I’ve been writing novels set in the seventeenth century for adults for quite a few years. During my research, I’ve often come across young women aged between fourteen and eighteen, and yet expected to run a household, accept adult responsibilities, marry and bear children. That was the way of life back then. When writing for adults, these heroines of 14 or 15 years of age seem unlikely – far too young to have such maturity. Yet for today’s teen readers of that age, the same characters can appear too mature, too ensconced in an adult life.

As Eliza Graham points out in her excellent article on Historical Fiction Connection, teenagers were not a separate group with their own rules and identity until the twentieth century.

As Eliza Graham points out in her excellent article on Historical Fiction Connection, teenagers were not a separate group with their own rules and identity until the twentieth century.I pondered on this on and off, as I’m sure it is a problem many historical fiction writers have grappled with, but I came to no definitive answer. Usually, if the character is too young to be behaving in a certain way by our modern standards, I’ll try not to mention her age in years, but just refer to her as ‘young’, for example. Or better, try to make sure the milieu in which she lives, supports and describes such a maturity.

When I came across the history of Lady Katherine Fanshawe – married at fourteen, and a highwaywoman (if we believe the legend) by eighteen, I was attracted to the story, but unsure exactly who would read it. The theme sounded as though it might be attractive to teenagers so I thought I would try writing for a younger age-group. I looked in my local bookshops for examples of historical fiction designed for readers 14 plus, and could find very few. This year at least, readers of that age, according to the bookstore owner, want fantasy and sorcery. To my relief, my local library (hooray!) yielded a much better and more varied stock, and I was able to plunge in, and try to see what creating a younger ‘voice’ might mean for me as a writer. Teen readers, like adult readers, I’m sure are of all different tastes.

What was immediately apparent was that the tone would have to be different from my adult novels. To create a younger voice, my characters would need to be more vibrant, less world-weary and more impetuous. Old-fashioned language would need to be replaced with something more direct. Shadow on the Highway feels more ‘modern’ than my other books, not least in the fact I had to find creative ways to reproduce seventeenth century versions of ‘OMG!’ I hope I have still kept some period authenticity. Immersing myself in the idealism of young people in the 17th century, led me to the Diggers – an early example of an alternative lifestyle, and one I thought might resonate with ecologically aware young readers today. (Read more about them here.)

An added difficulty for me was that the book would need to be shorter – it would be a rare teen that made it to the end of one of my other 500 page books (though I’m sure there are exceptions, including most of us writers when we were younger)! Fortunately the historical material neatly divides into three sections, and there are three main characters, so I thought the story might work as a trilogy. But a trilogy has its own three act structure, and the first book is necessarily quieter, building the bedrock for the rest of the action. With this in mind, the risk is, that if nobody enjoys the first book, it might founder at first base, and then I’d feel awkward spending time writing two more that nobody wants!

Books where I admired the creation of the teenage voice were Phillip Pullman’s Ruby in the Smoke, where the voice was lively and opinionated, something I wanted for my character Lady Katherine. I very much admired Code Name Verity, by Elizabeth Wein, but was aware that my book was not going to be quite so literary and was set a lot further in the past. I turned to Cassandra Clare’s books such as The Clockwork Princess, which had the right tone, but these books veer away from a purely historical setting with their steampunk approach. Here are some other authors with historical settings I enjoyed: Brian Jacques, Eva Ibbotson, Victoria Lamb, Celia Rees, Ann Turnbull, Anna Godbersen amongst others. If I was to highlight one I particularly liked, I would go for The Madman’s Daughter by Megan Shepherd, which had an outstanding sense of time and place.

Writing historical fiction for teens is every bit as demanding as writing for adults, more so, as my teen beta readers were frighteningly direct in their assessment. Some quite frankly didn’t like it. Some got bored. An immense amount of world-building has to go on in the head of the reader for historical fiction to work, and not all readers have a mental image bank yet that they can draw on to help them create the scene in their heads. But when you get a great response it is equally direct – and immensely rewarding. Especially when you have introduced them to a whole new genre of reading. I hope many adults will try some of these books too, after all, as Veronica Roth, author of the Divergent trilogy says, “I think everyone’s got a little teenager inside of them still, and you just have to work to help yourself access that teenager.”

~

Deborah Swift used to work in the theatre and at the BBC as a set and costume designer, before studying for an MA in Creative Writing in 2007. She lives in a beautiful area of Lancashire near the Lake District National Park. She is the author of The Lady’s Slipper and is a member of the Historical Writers Association, the Historical Novel Society, and the Romantic Novelists Association.

Deborah Swift used to work in the theatre and at the BBC as a set and costume designer, before studying for an MA in Creative Writing in 2007. She lives in a beautiful area of Lancashire near the Lake District National Park. She is the author of The Lady’s Slipper and is a member of the Historical Writers Association, the Historical Novel Society, and the Romantic Novelists Association.For more information, please visit Deborah’s website. You can also find her on Facebook and Twitter.

Shadow on the Highway was published in July in paperback and as an ebook (see Amazon UK or Amazon US).

Published on August 27, 2014 05:00

August 25, 2014

Book review: Lisette's List, by Susan Vreeland

In her moving latest novel, set in Provence between 1937 and 1948, Vreeland explores the power of art and how painters help us interpret our world. This involving work also traces one young woman’s maturation as she adjusts to a new life.

In her moving latest novel, set in Provence between 1937 and 1948, Vreeland explores the power of art and how painters help us interpret our world. This involving work also traces one young woman’s maturation as she adjusts to a new life.Although Lisette Roux resents leaving Paris with her husband, André, to care for his grandfather Pascal, she loves hearing Pascal reminisce about Pissarro and Cézanne. Their paintings and others, which hang on his walls, have immense personal and monetary value, so André conceals them before leaving to fight. Alone during wartime, Lisette endures tragedy and hardships while developing close friendships; they, and her mission to recover the paintings, drive her on.

The stunning countryside, with its ochre mines, fragrant orchards, and cold mistral, is passionately depicted, and Vreeland is an informed guide to the Impressionist through Modernist movements. The book’s most touching moments, though, intertwine art with human connections, such as how the love between Marc and Bella Chagall—in hiding from the Nazis in Provence—is evoked through his work.

Lisette's List is published tomorrow in hardcover by Random House ($27, 410pp). This review first appeared in Booklist's July issue.

Published on August 25, 2014 07:00

August 22, 2014

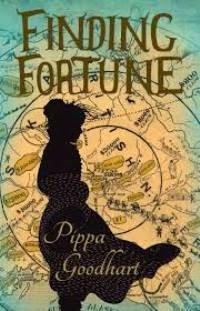

The background to Finding Fortune, an essay by Pippa Goodhart

Today British writer Pippa Goodhart speaks about the family artifacts and subsequent research that inspired Finding Fortune, her children's historical novel set at the time of the Klondike Gold Rush. Please read on!

~

The Background to Finding Fortune

Pippa Goodhart

When I was a child I would watch my mother getting ready to go out to occasional parties. It didn’t often happen, and my mother didn’t have a great range of jewellery to choose from. But she did have one ring which she would add to the wedding ring and engagement rings on her fingers, and this is it...

It is a Victorian ring made of gold, and holding a stone in which there is a splash of gold, just as nature laid it down. The ring had been given to my mother, Christine, by her mother, Dorothy, who had been given it by her mother, Florence, who had been given it by her mother, Polly, who had been given it by her brother, William James, when he came back from the Klondike Gold Rush. Here are Polly (who was blind) with daughter Florence.

What, and when, was the Klondike Gold Rush? I began researching, and what an amazing historical moment of madness it was! Fur trappers came upon great quantities of gold in the far north-east of Canada in 1896, and, when the summer thaw let them travel into Seattle in early 1897 the newspapers picked-up on the story of scruffy men arriving with suitcases and jam jars and pockets full of gold, apparently there for the taking. Over a hundred thousand people from all over the world then made the heroic/stupid journey to that remote place. Some found fortunes. Many more of them didn’t.

So a story began to grow in my mind. Ida’s lovely Ma has died, and now she and her father are being told what direction their lives should take by a domineering Grandmama. Ida is to go to boarding school, and Fa is to travel to some place in the Empire where he can make himself a living. Fa is going to try his luck in the Klondike … and Ida is determined to run away and go with him.

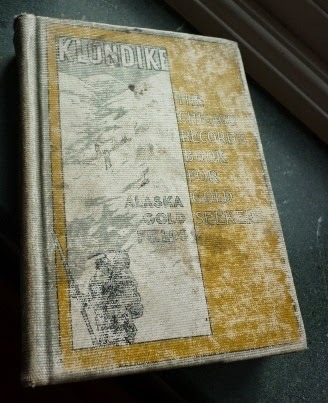

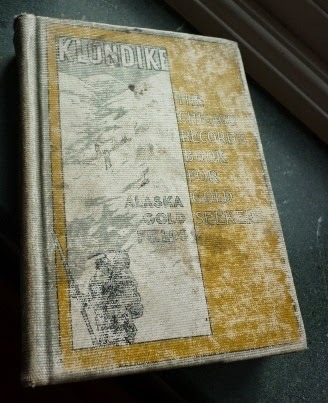

I had a wonderful time researching. There are photographs showing men and women dressed in adventuring outfits, posed in studios before they set off, and then hollow-eyed and desperate on trails lined with dead horses and hit with avalanches. I also found this book:

…selling cheaply because its cover is ‘worn and scuffed’ to such an extent that you can hardly read that it is The Chicago Record’s Guide For Gold Seekers, published in 1897. Inside are pristine pages, some clearly not even opened before. There are maps, there are boat routes and prices, there are instructions on how to extract gold, and there are long lists of all the equipment and food and clothing that you should take with you into that wild place, just short of the Arctic, where, of course, supplies are cut off for the long frozen dark winter months. That book must surely have gone to the Klondike in somebody’s ‘outfit’! I was handling a book that had lived the adventure of the Gold Rush! Gosh, I do love research!

That research soon showed that the bulk of Ida’s story would be taken-up with the journey to get to Dawson and the Klondike area. By boat from England to the east coast of Canada, across Canada by train, down to Seattle to buy supplies, then a rickety and overfilled ship up the west coast to the tent encampment at Dyea before beginning the notorious Chilkoot Pass trail into the mountains.

Then building a boat and waiting for the thaw, until the race amongst the thousands to get down the river in time to find a patch of land to search for gold before winter hit again.

Unusually, with this story I began writing before I knew what the ending would be. I didn’t know whether or not Ida and Fa would find gold. If they did, that would feel a bit too easy, and very different from the experiences of most of the ‘Argonauts’. But if they didn’t find gold, wouldn’t that feel an anti-climax for the story after all those months and thousands of miles of travelling? As I wrote, this story seemed to take on a life of its own. I was chasing after it, writing it down, rather than having to drag it along as you do with some stories. The story development and ending just revealed itself, taking me by surprise! If you want to know how, then you’ll have to read the story!

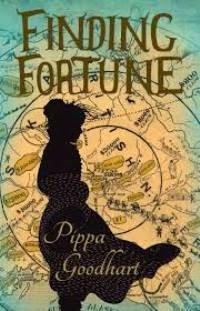

Footnote: The book’s cover shows a silhouette of Ida against a background provided by a board game from 1897, which the publisher cleverly found, showing mountains and claims and Indians and Gold Rush people, moose, dogs, and more.

PS: My lovely Mum has now given that ring to me. And, yes, it does appear in the story.

~

Finding Fortune was published by Catnip Publishing in 2013 (trade pb, 251pp). Visit the author's website at http://www.pippagoodhart.co.uk.

~

The Background to Finding Fortune

Pippa Goodhart

When I was a child I would watch my mother getting ready to go out to occasional parties. It didn’t often happen, and my mother didn’t have a great range of jewellery to choose from. But she did have one ring which she would add to the wedding ring and engagement rings on her fingers, and this is it...

It is a Victorian ring made of gold, and holding a stone in which there is a splash of gold, just as nature laid it down. The ring had been given to my mother, Christine, by her mother, Dorothy, who had been given it by her mother, Florence, who had been given it by her mother, Polly, who had been given it by her brother, William James, when he came back from the Klondike Gold Rush. Here are Polly (who was blind) with daughter Florence.

What, and when, was the Klondike Gold Rush? I began researching, and what an amazing historical moment of madness it was! Fur trappers came upon great quantities of gold in the far north-east of Canada in 1896, and, when the summer thaw let them travel into Seattle in early 1897 the newspapers picked-up on the story of scruffy men arriving with suitcases and jam jars and pockets full of gold, apparently there for the taking. Over a hundred thousand people from all over the world then made the heroic/stupid journey to that remote place. Some found fortunes. Many more of them didn’t.

So a story began to grow in my mind. Ida’s lovely Ma has died, and now she and her father are being told what direction their lives should take by a domineering Grandmama. Ida is to go to boarding school, and Fa is to travel to some place in the Empire where he can make himself a living. Fa is going to try his luck in the Klondike … and Ida is determined to run away and go with him.

I had a wonderful time researching. There are photographs showing men and women dressed in adventuring outfits, posed in studios before they set off, and then hollow-eyed and desperate on trails lined with dead horses and hit with avalanches. I also found this book:

…selling cheaply because its cover is ‘worn and scuffed’ to such an extent that you can hardly read that it is The Chicago Record’s Guide For Gold Seekers, published in 1897. Inside are pristine pages, some clearly not even opened before. There are maps, there are boat routes and prices, there are instructions on how to extract gold, and there are long lists of all the equipment and food and clothing that you should take with you into that wild place, just short of the Arctic, where, of course, supplies are cut off for the long frozen dark winter months. That book must surely have gone to the Klondike in somebody’s ‘outfit’! I was handling a book that had lived the adventure of the Gold Rush! Gosh, I do love research!

That research soon showed that the bulk of Ida’s story would be taken-up with the journey to get to Dawson and the Klondike area. By boat from England to the east coast of Canada, across Canada by train, down to Seattle to buy supplies, then a rickety and overfilled ship up the west coast to the tent encampment at Dyea before beginning the notorious Chilkoot Pass trail into the mountains.

Then building a boat and waiting for the thaw, until the race amongst the thousands to get down the river in time to find a patch of land to search for gold before winter hit again.

Unusually, with this story I began writing before I knew what the ending would be. I didn’t know whether or not Ida and Fa would find gold. If they did, that would feel a bit too easy, and very different from the experiences of most of the ‘Argonauts’. But if they didn’t find gold, wouldn’t that feel an anti-climax for the story after all those months and thousands of miles of travelling? As I wrote, this story seemed to take on a life of its own. I was chasing after it, writing it down, rather than having to drag it along as you do with some stories. The story development and ending just revealed itself, taking me by surprise! If you want to know how, then you’ll have to read the story!

Footnote: The book’s cover shows a silhouette of Ida against a background provided by a board game from 1897, which the publisher cleverly found, showing mountains and claims and Indians and Gold Rush people, moose, dogs, and more.

PS: My lovely Mum has now given that ring to me. And, yes, it does appear in the story.

~

Finding Fortune was published by Catnip Publishing in 2013 (trade pb, 251pp). Visit the author's website at http://www.pippagoodhart.co.uk.

Published on August 22, 2014 05:00

August 19, 2014

Book review: Liberty Silk, by Kate Beaufoy

When I first read the catalog description for Kate Beaufoy’s Liberty Silk, I’d pegged it for a traditional saga about independent 20th-century women, one which would whisk me away to stylish locales and eras and make for an agreeable diversion over a summer afternoon or two.

What I got was much more. I was wowed by this book: by the author’s sparkling language, the wistful ambiance, the stunning settings, and the genuineness of its heroines. Although I enjoy historical novels about glitz and glamour, they often have a heartlessness at their core which keeps me at a distance. This isn’t the case here. The main characters, each of whom is very different, have a vulnerability that remains with them despite the life-changing experiences they endure.

What I got was much more. I was wowed by this book: by the author’s sparkling language, the wistful ambiance, the stunning settings, and the genuineness of its heroines. Although I enjoy historical novels about glitz and glamour, they often have a heartlessness at their core which keeps me at a distance. This isn’t the case here. The main characters, each of whom is very different, have a vulnerability that remains with them despite the life-changing experiences they endure.

The story intertwines the stories of three women from adjacent generations. Born into a wealthy London family, Jessie Beaufoy follows her heart and marries a handsome artist, only to have him abandon her on the final day of their honeymoon in Finistère on the Brittany coast. An eternal romantic, Jessie is despondent and longs to find him again – but her reduced circumstances and the corresponding shame persuade her to accept a role as muse to a famous painter in postwar Paris and on the Riviera.

Twenty years later, gregarious Baba MacLeod escapes London for a career in Hollywood, reinventing herself as an actor’s personal assistant and, later, as film star Lisa La Touche. Although she becomes a household name, she’s devastated by the rampant hypocrisy and the codes of conduct she’s obliged to adhere to. Finally, in the mid-1960s, Cat leaves her beloved parents in rural Connemara, Ireland, to become a war photographer.

Threaded like a silver chain through both Jessie’s and Lisa’s stories is the theme of how women’s freedom is held in check by men. Only Cat, living through the more relaxed social norms of the 1960s, has the opportunity to direct her life as she chooses.

And, yes – the dress on the cover. One other element linking the women is a custom-designed crepe de Chine gown from Liberty of London that’s “tiered like a Grecian tunic: a classic Doric column when one stood still in motion, a swirl of colour – primrose and geranium and cornflower blue and moss green.” Although it doesn’t play a large role in the story, it comes to symbolize where they came from as well as their connectedness.

Liberty Silk is high-class literary entertainment. The author was inspired by letters sent home from Paris and Italy by Jessie Beaufoy, her grandmother, who must have been a remarkable woman. Her novel makes for a beautiful homage to the real-life Jessie and to all women who aim to follow their dreams.

The novel was published as a paperback original by Transworld Ireland in July (£6.99, 496pp). Thanks to the publisher for sending me a copy at my request.

What I got was much more. I was wowed by this book: by the author’s sparkling language, the wistful ambiance, the stunning settings, and the genuineness of its heroines. Although I enjoy historical novels about glitz and glamour, they often have a heartlessness at their core which keeps me at a distance. This isn’t the case here. The main characters, each of whom is very different, have a vulnerability that remains with them despite the life-changing experiences they endure.

What I got was much more. I was wowed by this book: by the author’s sparkling language, the wistful ambiance, the stunning settings, and the genuineness of its heroines. Although I enjoy historical novels about glitz and glamour, they often have a heartlessness at their core which keeps me at a distance. This isn’t the case here. The main characters, each of whom is very different, have a vulnerability that remains with them despite the life-changing experiences they endure.The story intertwines the stories of three women from adjacent generations. Born into a wealthy London family, Jessie Beaufoy follows her heart and marries a handsome artist, only to have him abandon her on the final day of their honeymoon in Finistère on the Brittany coast. An eternal romantic, Jessie is despondent and longs to find him again – but her reduced circumstances and the corresponding shame persuade her to accept a role as muse to a famous painter in postwar Paris and on the Riviera.

Twenty years later, gregarious Baba MacLeod escapes London for a career in Hollywood, reinventing herself as an actor’s personal assistant and, later, as film star Lisa La Touche. Although she becomes a household name, she’s devastated by the rampant hypocrisy and the codes of conduct she’s obliged to adhere to. Finally, in the mid-1960s, Cat leaves her beloved parents in rural Connemara, Ireland, to become a war photographer.