Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 87

September 12, 2015

Historical fiction cover trend: Scenes of the coastline

Inspired by the fact that I've recently read three of these novels and am currently reading a fourth.

Moreton Bay, Australia, in 1891 and a century later.

Moreton Bay, Australia, in 1891 and a century later.

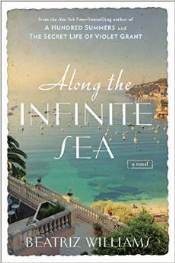

The rocky Corsican coast, from the 1920s through the 1980s.

The rocky Corsican coast, from the 1920s through the 1980s.

Newport, Rhode Island, summer home of America's blue-blooded elite in the Gilded Age.

Newport, Rhode Island, summer home of America's blue-blooded elite in the Gilded Age.

The ritzy resort city of Famagusta, Cyprus, in the 1970s (see review).

The ritzy resort city of Famagusta, Cyprus, in the 1970s (see review).

Wealthy expat life along the coast of Antibes in the Roaring '20s.

Wealthy expat life along the coast of Antibes in the Roaring '20s.

A mystery set along the French Riviera in the postwar period.

A mystery set along the French Riviera in the postwar period.

Sunny Portugal in the present day and during the WWII years. An April '16 release.

Sunny Portugal in the present day and during the WWII years. An April '16 release.

Romance and secrets at a Mediterranean seaside resort, from 1948 to today.

Romance and secrets at a Mediterranean seaside resort, from 1948 to today.

Gothic fiction set in a seaside resort in Kent in the 1850s.

Gothic fiction set in a seaside resort in Kent in the 1850s.

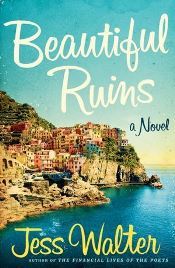

Romance alongside the Ligurian Sea in the year 1962.

Romance alongside the Ligurian Sea in the year 1962.

The beautiful French Riviera in the late 1930s.

The beautiful French Riviera in the late 1930s.

Moreton Bay, Australia, in 1891 and a century later.

Moreton Bay, Australia, in 1891 and a century later. The rocky Corsican coast, from the 1920s through the 1980s.

The rocky Corsican coast, from the 1920s through the 1980s. Newport, Rhode Island, summer home of America's blue-blooded elite in the Gilded Age.

Newport, Rhode Island, summer home of America's blue-blooded elite in the Gilded Age. The ritzy resort city of Famagusta, Cyprus, in the 1970s (see review).

The ritzy resort city of Famagusta, Cyprus, in the 1970s (see review). Wealthy expat life along the coast of Antibes in the Roaring '20s.

Wealthy expat life along the coast of Antibes in the Roaring '20s. A mystery set along the French Riviera in the postwar period.

A mystery set along the French Riviera in the postwar period. Sunny Portugal in the present day and during the WWII years. An April '16 release.

Sunny Portugal in the present day and during the WWII years. An April '16 release. Romance and secrets at a Mediterranean seaside resort, from 1948 to today.

Romance and secrets at a Mediterranean seaside resort, from 1948 to today. Gothic fiction set in a seaside resort in Kent in the 1850s.

Gothic fiction set in a seaside resort in Kent in the 1850s. Romance alongside the Ligurian Sea in the year 1962.

Romance alongside the Ligurian Sea in the year 1962. The beautiful French Riviera in the late 1930s.

The beautiful French Riviera in the late 1930s.

Published on September 12, 2015 08:22

September 8, 2015

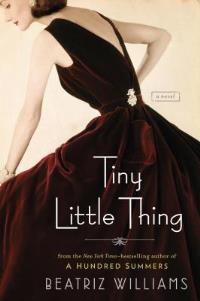

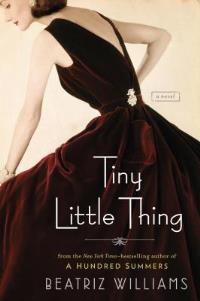

1960s society and secrets: Tiny Little Thing, by Beatriz Williams

Beatriz Williams’ novels are deliciously addictive. Although her latest is a less complex story than The Secret Life of Violet Grant (see review), it has the same winning combination of intriguing characters, zippy prose, and realistic dialogue.

Unlike her exuberant younger sister Vivian, one of the previous book’s heroines, Christina “Tiny” Hardcastle had been groomed to be the perfect hostess and spouse. By marrying handsome Frank, an aspiring Congressman, she has achieved her and her family’s goal – yet feels the weight of responsibility upon her petite shoulders. She appears to have the support of her husband and his formidable family, especially after her recent miscarriage, but in the summer of ’66, which the Hardcastles spend together, Kennedy-style, on Cape Cod, Tiny’s perfect world starts falling apart.

Unlike her exuberant younger sister Vivian, one of the previous book’s heroines, Christina “Tiny” Hardcastle had been groomed to be the perfect hostess and spouse. By marrying handsome Frank, an aspiring Congressman, she has achieved her and her family’s goal – yet feels the weight of responsibility upon her petite shoulders. She appears to have the support of her husband and his formidable family, especially after her recent miscarriage, but in the summer of ’66, which the Hardcastles spend together, Kennedy-style, on Cape Cod, Tiny’s perfect world starts falling apart.

First an incriminating photo and blackmailed threat arrive in the mail, and then her secret former lover, Frank’s cousin Caspian, returns from Vietnam a war hero and helps bolster Frank’s first political campaign. Caspian seems honorable and trustworthy, so Tiny can’t imagine he’d be blackmailing her – but how did the photos he took get into someone else’s hands? And thanks to a reporter’s questions and her own intuition, she suspects Frank’s hiding something, too. Providing unexpected moral support is Tiny’s beautiful sister, Pepper, whose adventures in the forthcoming Along the Infinite Sea promise to be most excellent.

Novels showing the downsides of life among the glamorous elite are hardly new, but Tiny’s sympathetic and engaging voice, even addressing the reader on occasion, ensures she isn’t a cliché. The plight of returning Vietnam soldiers is touched upon only lightly, and Caspian feels a bit idealized, but in showing the pressures endured by celebrities of both genders, the novel sends a heartfelt message about the struggles everyone faces between our public and private selves.

Tiny Little Thing was published by Putnam in June ($26.95 or Can$33.00, hb, 386pp). This review first appeared in August's Historical Novels Review.

Unlike her exuberant younger sister Vivian, one of the previous book’s heroines, Christina “Tiny” Hardcastle had been groomed to be the perfect hostess and spouse. By marrying handsome Frank, an aspiring Congressman, she has achieved her and her family’s goal – yet feels the weight of responsibility upon her petite shoulders. She appears to have the support of her husband and his formidable family, especially after her recent miscarriage, but in the summer of ’66, which the Hardcastles spend together, Kennedy-style, on Cape Cod, Tiny’s perfect world starts falling apart.

Unlike her exuberant younger sister Vivian, one of the previous book’s heroines, Christina “Tiny” Hardcastle had been groomed to be the perfect hostess and spouse. By marrying handsome Frank, an aspiring Congressman, she has achieved her and her family’s goal – yet feels the weight of responsibility upon her petite shoulders. She appears to have the support of her husband and his formidable family, especially after her recent miscarriage, but in the summer of ’66, which the Hardcastles spend together, Kennedy-style, on Cape Cod, Tiny’s perfect world starts falling apart. First an incriminating photo and blackmailed threat arrive in the mail, and then her secret former lover, Frank’s cousin Caspian, returns from Vietnam a war hero and helps bolster Frank’s first political campaign. Caspian seems honorable and trustworthy, so Tiny can’t imagine he’d be blackmailing her – but how did the photos he took get into someone else’s hands? And thanks to a reporter’s questions and her own intuition, she suspects Frank’s hiding something, too. Providing unexpected moral support is Tiny’s beautiful sister, Pepper, whose adventures in the forthcoming Along the Infinite Sea promise to be most excellent.

Novels showing the downsides of life among the glamorous elite are hardly new, but Tiny’s sympathetic and engaging voice, even addressing the reader on occasion, ensures she isn’t a cliché. The plight of returning Vietnam soldiers is touched upon only lightly, and Caspian feels a bit idealized, but in showing the pressures endured by celebrities of both genders, the novel sends a heartfelt message about the struggles everyone faces between our public and private selves.

Tiny Little Thing was published by Putnam in June ($26.95 or Can$33.00, hb, 386pp). This review first appeared in August's Historical Novels Review.

Published on September 08, 2015 12:46

September 2, 2015

Tales of innocence and experience: Annie Barrows' The Truth According to Us

Every family has hidden stories in its past. Tales of love and togetherness, others of disappointment, betrayal, even tragedy. Posed black-and-white photos can only hint at the day-to-day specifics of our forebears' lives. The only way to know the truth is if you were there.

But, as suggested by Annie Barrows’ (co-author of The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society) first standalone novel for adults, sometimes even that isn’t enough. As one wise character notes early on, “All of us see a story according to our own lights.” Sifting through remembrances, anecdotes, and other evidence to discover what really happened can be tough, painful work.

But, as suggested by Annie Barrows’ (co-author of The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society) first standalone novel for adults, sometimes even that isn’t enough. As one wise character notes early on, “All of us see a story according to our own lights.” Sifting through remembrances, anecdotes, and other evidence to discover what really happened can be tough, painful work.

Perceptive and engrossing, and with a host of characters you’ll regret having to leave after it's over, the appropriately-named The Truth According to Us has a trio of threads that address this issue. One takes a fairly light tone while the others are more serious and progressively more suspenseful, and they all overlap and intertwine.

The story opens during the stifling summer of 1938. Cut off financially by her parents after rejecting a blue-blooded but stuffy suitor, Layla Beck gets assigned to write the history of Macedonia, West Virginia as part of the WPA Federal Writers’ Project. Sharply intelligent but privileged, she isn’t used to a regular job. (As her field supervisor – who happens to be her uncle – writes to a colleague, “When she came down for her interview, I was pleasantly surprised to discover she had heard there was a depression.”) Layla also isn’t thrilled about possibly spending the summer in an impoverished backwater full of “toothless old hicks.”

The Romeyns, the family she boards with, have come down in society. Their late patriarch used to run the local hosiery factory, but a mysterious fire 18 years ago changed everything. Fortunately for Layla, the Romeyns’ home is cleanly appointed, and they themselves have their own quirky charms, especially Felix, a “terribly attractive” divorced father of two. As Layla interviews descendants of Macedonia’s “first families” for her book (and gets closer to Felix), she has to decide which “facts” to believe, both about the town’s past and her would-be lover.

Meanwhile, twelve-year-old Willa Romeyn, Felix’s elder daughter, gets curious about her father’s frequent absences. Is he really a chemical salesman, or maybe something more nefarious? Here Barrows, a prolific children’s author, demonstrates her familiarity with writing from a not-quite-adolescent’s viewpoint. Willa’s got some Harriet the Spy in her, narrating her sections in a voice that’s observant and funny, if almost too precocious in places. It’s also gratifying to see the town librarian encourage Willa’s book habit.

Yet it’s Willa’s Aunt Jottie, who essentially raises her and her strong-willed sister Bird, whose backstory is the most affecting. An attractive spinster of 35, Jottie's hopes for romance were stifled years back, in an incident she can’t quite get over or fully comprehend. While she’s grown accustomed to her sedate life, Jottie will do anything – joining the dull local ladies’ society included – to keep her family respectable and ensure Willa and Bird don’t grow up too quickly.

Their family home contains a compelling mix of innocence and experience, but the former can’t last forever. People's stories converge, revelations unfold, and the repercussions shake everyone up. The muggy Southern summer is evoked to perfection, with regular afternoon naps and doses of iced-tea, and the equally sizzling family dynamics, with Layla as the unsuspecting catalyst, drive the plot onward. As she gossips in a letter to a friend, Macedonia is “a small town that looks like any small town, with wide streets, old elms, white houses, and a tattered, dead-quiet town square – all seething with white-hot passion and Greek tragedy.”

However, as Jottie remarks with equal truth in one poignant section, small town life just doesn’t change much over the years. This feeling of “sameness,” as she puts it, can provide both frustration and comfort. This is one of many ways the novel gives off the whiff of real life. Macedonia’s residents feel as tangible as one’s own family, and it’s in its honest depiction of people’s capacity for love, protectiveness, and understanding that the story shines.

The Truth According to Us was published by The Dial Press/Random House in June ($28.00, hardcover, 512pp). I requested it on NetGalley and subsequently received a print ARC from Shelf Awareness, a true embarrassment of riches! It will make my top 10 of the year.

But, as suggested by Annie Barrows’ (co-author of The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society) first standalone novel for adults, sometimes even that isn’t enough. As one wise character notes early on, “All of us see a story according to our own lights.” Sifting through remembrances, anecdotes, and other evidence to discover what really happened can be tough, painful work.

But, as suggested by Annie Barrows’ (co-author of The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society) first standalone novel for adults, sometimes even that isn’t enough. As one wise character notes early on, “All of us see a story according to our own lights.” Sifting through remembrances, anecdotes, and other evidence to discover what really happened can be tough, painful work. Perceptive and engrossing, and with a host of characters you’ll regret having to leave after it's over, the appropriately-named The Truth According to Us has a trio of threads that address this issue. One takes a fairly light tone while the others are more serious and progressively more suspenseful, and they all overlap and intertwine.

The story opens during the stifling summer of 1938. Cut off financially by her parents after rejecting a blue-blooded but stuffy suitor, Layla Beck gets assigned to write the history of Macedonia, West Virginia as part of the WPA Federal Writers’ Project. Sharply intelligent but privileged, she isn’t used to a regular job. (As her field supervisor – who happens to be her uncle – writes to a colleague, “When she came down for her interview, I was pleasantly surprised to discover she had heard there was a depression.”) Layla also isn’t thrilled about possibly spending the summer in an impoverished backwater full of “toothless old hicks.”

The Romeyns, the family she boards with, have come down in society. Their late patriarch used to run the local hosiery factory, but a mysterious fire 18 years ago changed everything. Fortunately for Layla, the Romeyns’ home is cleanly appointed, and they themselves have their own quirky charms, especially Felix, a “terribly attractive” divorced father of two. As Layla interviews descendants of Macedonia’s “first families” for her book (and gets closer to Felix), she has to decide which “facts” to believe, both about the town’s past and her would-be lover.

Meanwhile, twelve-year-old Willa Romeyn, Felix’s elder daughter, gets curious about her father’s frequent absences. Is he really a chemical salesman, or maybe something more nefarious? Here Barrows, a prolific children’s author, demonstrates her familiarity with writing from a not-quite-adolescent’s viewpoint. Willa’s got some Harriet the Spy in her, narrating her sections in a voice that’s observant and funny, if almost too precocious in places. It’s also gratifying to see the town librarian encourage Willa’s book habit.

Yet it’s Willa’s Aunt Jottie, who essentially raises her and her strong-willed sister Bird, whose backstory is the most affecting. An attractive spinster of 35, Jottie's hopes for romance were stifled years back, in an incident she can’t quite get over or fully comprehend. While she’s grown accustomed to her sedate life, Jottie will do anything – joining the dull local ladies’ society included – to keep her family respectable and ensure Willa and Bird don’t grow up too quickly.

Their family home contains a compelling mix of innocence and experience, but the former can’t last forever. People's stories converge, revelations unfold, and the repercussions shake everyone up. The muggy Southern summer is evoked to perfection, with regular afternoon naps and doses of iced-tea, and the equally sizzling family dynamics, with Layla as the unsuspecting catalyst, drive the plot onward. As she gossips in a letter to a friend, Macedonia is “a small town that looks like any small town, with wide streets, old elms, white houses, and a tattered, dead-quiet town square – all seething with white-hot passion and Greek tragedy.”

However, as Jottie remarks with equal truth in one poignant section, small town life just doesn’t change much over the years. This feeling of “sameness,” as she puts it, can provide both frustration and comfort. This is one of many ways the novel gives off the whiff of real life. Macedonia’s residents feel as tangible as one’s own family, and it’s in its honest depiction of people’s capacity for love, protectiveness, and understanding that the story shines.

The Truth According to Us was published by The Dial Press/Random House in June ($28.00, hardcover, 512pp). I requested it on NetGalley and subsequently received a print ARC from Shelf Awareness, a true embarrassment of riches! It will make my top 10 of the year.

Published on September 02, 2015 13:02

August 31, 2015

The ambassador's controversial concubine: Alexandra Curry's The Courtesan

Curry’s debut is the first English-language novel about the controversial courtesan Sai Jinhua, whose unusual life path reached a crisis during the 1900 Boxer Rebellion.

Curry’s debut is the first English-language novel about the controversial courtesan Sai Jinhua, whose unusual life path reached a crisis during the 1900 Boxer Rebellion.At seven, after her mandarin father’s execution, she is sold to a cruel brothel-mistress, who trains her as a “money tree” (prostitute). “You do not own yourself,” the maid Suyin warns her, and their sisterly bond helps them survive.

Surprisingly, an official makes Jinhua his concubine, bringing her to Vienna just as Europeans, hated for their corrupt influence, are dismantling the Chinese empire. Buoyant with curiosity about Austro-Hungarian culture, Jinhua discovers her Western sympathies have a price.

The smooth-as-silk prose, flavored with details of Chinese customs and Jinhua’s favorite mythological stories, heightens the sense that we’re hearing a legend retold. At the same time, her pain and heartbreak anchor the telling in reality.

Multiple viewpoints add dimension and depth. The later sections feel rushed, and the novel doesn’t fully address the reasons for her celebrity, but this creative and haunting interpretation spurs interest in the real Sai Jinhua.

The Courtesan will be published by Dutton next week in hardcover ($26.95, 400pp). This review first appeared in Booklist's August issue. Despite her fame, I hadn't heard of Sai Jinhua before beginning this novel, and it encouraged me to learn more - although (as noted in the book) it's hard to get a true picture of her life because it's difficult to separate history from the legend. This version is one author's interpretation.

Published on August 31, 2015 11:43

August 28, 2015

Book review: Orphan #8 by Kim van Alkemade

With her first book, Kim van Alkemade has struck a perfect balance that many historical novelists struggle to attain. The rapid, page-turning pacing is never impeded by the wealth of intriguing detail she includes on a little-known segment of history: the plight of children in Jewish orphanages in early 20th-century New York.

“From her bed of bundled newspapers under the kitchen table, Rachel Rabinowitz watched her mother’s bare feet shuffle to the sink.” The first sentence does its job well, setting the scene while posing questions about Rachel's situation. A four-year-old living with her older brother, Sam, and their parents and boarders in a shabby tenement on Manhattan’s Lower East Side in 1919, Rachel is an active, inquisitive child.

“From her bed of bundled newspapers under the kitchen table, Rachel Rabinowitz watched her mother’s bare feet shuffle to the sink.” The first sentence does its job well, setting the scene while posing questions about Rachel's situation. A four-year-old living with her older brother, Sam, and their parents and boarders in a shabby tenement on Manhattan’s Lower East Side in 1919, Rachel is an active, inquisitive child.

By the end of the day, their circumstances tragically altered, the siblings are put in the care of social workers. At the Hebrew Infant Home, separated from Sam, Rachel experiences horrifying treatment in the name of medical research. She and other orphans become the ideal subjects in an experimental X-ray lab under the supervision of Dr. Mildred Solomon, a woman seeking to make her mark in a male-dominated field. The scenes at the home are emotionally powerful and disturbing, whether seen from the viewpoint of an innocent child or the matter-of-fact, detached perspective of the doctors.

Years later, in 1954, the two meet up again, but this time Rachel is Dr. Solomon's nurse at the Old Hebrews Home – where Dr. Solomon is dying of cancer. As Rachel’s faint childhood memories drive her to uncover her real role in the doctor’s research, she runs up against an ethical dilemma. While she’s doped up on morphine, Dr. Solomon can’t give Rachel the answers – or the apology – she seeks.

As Rachel contemplates her options, grasping the power she holds over another’s fate, the novel teeters on the edge of melodrama. The two timelines are well structured and contribute to the full picture of Rachel’s growth and development, and how her unusual upbringing in an orphanage, alongside a thousand other children, ultimately led to her career choice. Also, as a lesbian in the repressive 1950s, Rachel must keep her love life secret, and the novel depicts the different faces that Rachel presents to the world.

Both the experiments and young Rachel’s experiences are based on real-life history; the author’s grandfather (Victor, a friend of Sam's in the novel) grew up in a Hebrew orphanage, with his mother working as the Reception House counselor there. In addition to picking up a new angle on American history, readers will leave this compelling novel pondering choices and alternatives, responsibilities and their consequences. Orphan #8 is Target’s August book club pick, and with its courageous take on important ethical issues, it’s an excellent choice for book discussions.

Kim van Alkemade's Orphan #8 was published this summer by Morrow ($14.99/C$18.50, pb, 381pp). Thanks to the publisher for sending me an ARC.

“From her bed of bundled newspapers under the kitchen table, Rachel Rabinowitz watched her mother’s bare feet shuffle to the sink.” The first sentence does its job well, setting the scene while posing questions about Rachel's situation. A four-year-old living with her older brother, Sam, and their parents and boarders in a shabby tenement on Manhattan’s Lower East Side in 1919, Rachel is an active, inquisitive child.

“From her bed of bundled newspapers under the kitchen table, Rachel Rabinowitz watched her mother’s bare feet shuffle to the sink.” The first sentence does its job well, setting the scene while posing questions about Rachel's situation. A four-year-old living with her older brother, Sam, and their parents and boarders in a shabby tenement on Manhattan’s Lower East Side in 1919, Rachel is an active, inquisitive child. By the end of the day, their circumstances tragically altered, the siblings are put in the care of social workers. At the Hebrew Infant Home, separated from Sam, Rachel experiences horrifying treatment in the name of medical research. She and other orphans become the ideal subjects in an experimental X-ray lab under the supervision of Dr. Mildred Solomon, a woman seeking to make her mark in a male-dominated field. The scenes at the home are emotionally powerful and disturbing, whether seen from the viewpoint of an innocent child or the matter-of-fact, detached perspective of the doctors.

Years later, in 1954, the two meet up again, but this time Rachel is Dr. Solomon's nurse at the Old Hebrews Home – where Dr. Solomon is dying of cancer. As Rachel’s faint childhood memories drive her to uncover her real role in the doctor’s research, she runs up against an ethical dilemma. While she’s doped up on morphine, Dr. Solomon can’t give Rachel the answers – or the apology – she seeks.

As Rachel contemplates her options, grasping the power she holds over another’s fate, the novel teeters on the edge of melodrama. The two timelines are well structured and contribute to the full picture of Rachel’s growth and development, and how her unusual upbringing in an orphanage, alongside a thousand other children, ultimately led to her career choice. Also, as a lesbian in the repressive 1950s, Rachel must keep her love life secret, and the novel depicts the different faces that Rachel presents to the world.

Both the experiments and young Rachel’s experiences are based on real-life history; the author’s grandfather (Victor, a friend of Sam's in the novel) grew up in a Hebrew orphanage, with his mother working as the Reception House counselor there. In addition to picking up a new angle on American history, readers will leave this compelling novel pondering choices and alternatives, responsibilities and their consequences. Orphan #8 is Target’s August book club pick, and with its courageous take on important ethical issues, it’s an excellent choice for book discussions.

Kim van Alkemade's Orphan #8 was published this summer by Morrow ($14.99/C$18.50, pb, 381pp). Thanks to the publisher for sending me an ARC.

Published on August 28, 2015 06:00

August 24, 2015

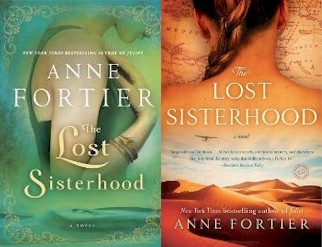

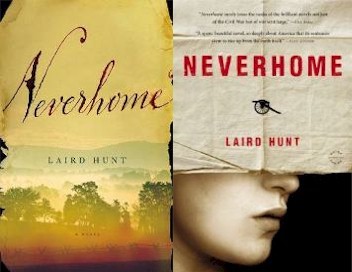

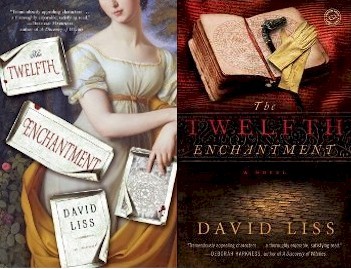

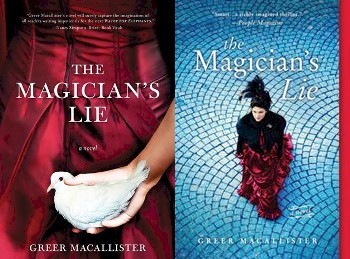

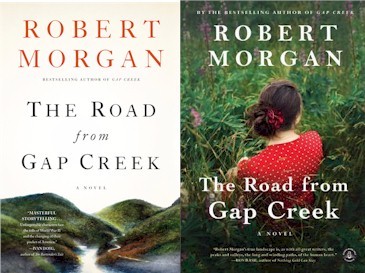

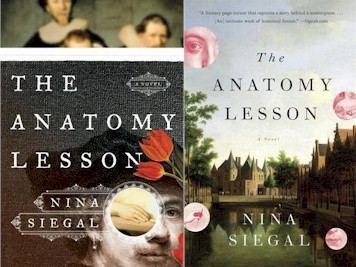

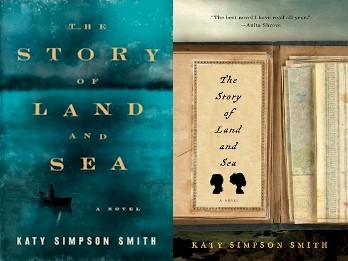

Historical fiction paperback makeovers

Some historical novels first released in hardcover undergo cover redesigns for their paperback printings. This can be done for a variety of reasons. Maybe the hardcover design wasn't as successful as intended, the publisher wants to take the book in a new direction, or there's a feeling that a design reboot would bring in new readers, like book club audiences. Trade paperbacks are a popular format for reading groups.

As you probably know, cover art is a favorite topic of mine, and I always find these design changes interesting for the new perspectives they provide. Here are a dozen pairings below: original hardcover design on the left, new paperback on the right. I've listed just a snippet about the setting as background for readers not familiar with the books. Which ones draw you in the most?

A dual period mystery centering on the ancient Amazons.

A dual period mystery centering on the ancient Amazons.

Gender-bending Civil War novel.

Gender-bending Civil War novel.

Magical Regency-era adventure.

Magical Regency-era adventure.

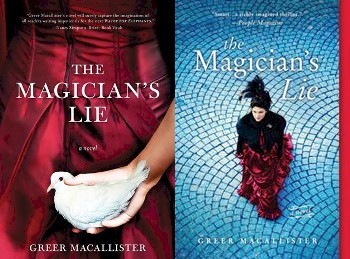

A female illusionist in Gilded Age America.

A female illusionist in Gilded Age America.

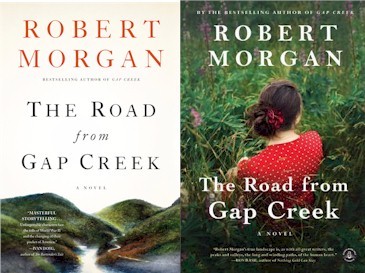

A family in Depression-era and WWII Appalachia.

A family in Depression-era and WWII Appalachia.

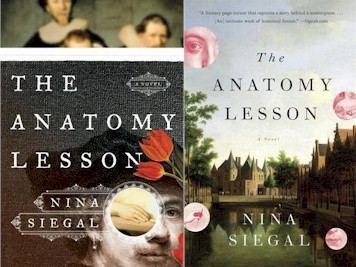

Story of a Rembrandt painting, set during the Dutch Golden Age.

Story of a Rembrandt painting, set during the Dutch Golden Age.

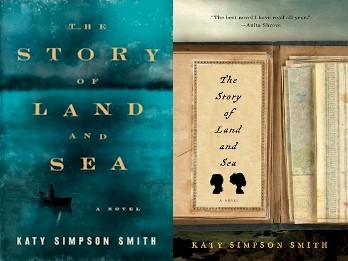

Literary family saga, set in Revolutionary-era North Carolina.

Literary family saga, set in Revolutionary-era North Carolina.

The tragedy of the Great War, as seen through four men's eyes. UK edition.

The tragedy of the Great War, as seen through four men's eyes. UK edition.

A teenage girl in an 1840s Shaker community.

A teenage girl in an 1840s Shaker community.

A US army nurse in WWII Italy.

A US army nurse in WWII Italy.

Novel-in-stories centering on an English country house.

Novel-in-stories centering on an English country house.

Multi-period romantic mystery set in 2009 and in pre-Raphaelite England.

Multi-period romantic mystery set in 2009 and in pre-Raphaelite England.

As you probably know, cover art is a favorite topic of mine, and I always find these design changes interesting for the new perspectives they provide. Here are a dozen pairings below: original hardcover design on the left, new paperback on the right. I've listed just a snippet about the setting as background for readers not familiar with the books. Which ones draw you in the most?

A dual period mystery centering on the ancient Amazons.

A dual period mystery centering on the ancient Amazons. Gender-bending Civil War novel.

Gender-bending Civil War novel. Magical Regency-era adventure.

Magical Regency-era adventure. A female illusionist in Gilded Age America.

A female illusionist in Gilded Age America. A family in Depression-era and WWII Appalachia.

A family in Depression-era and WWII Appalachia. Story of a Rembrandt painting, set during the Dutch Golden Age.

Story of a Rembrandt painting, set during the Dutch Golden Age. Literary family saga, set in Revolutionary-era North Carolina.

Literary family saga, set in Revolutionary-era North Carolina. The tragedy of the Great War, as seen through four men's eyes. UK edition.

The tragedy of the Great War, as seen through four men's eyes. UK edition. A teenage girl in an 1840s Shaker community.

A teenage girl in an 1840s Shaker community. A US army nurse in WWII Italy.

A US army nurse in WWII Italy. Novel-in-stories centering on an English country house.

Novel-in-stories centering on an English country house. Multi-period romantic mystery set in 2009 and in pre-Raphaelite England.

Multi-period romantic mystery set in 2009 and in pre-Raphaelite England.

Published on August 24, 2015 10:00

August 20, 2015

The Sunrise by Victoria Hislop, a splashy beach read turned war story

In the summer of 1972, the city of Famagusta on Cyprus is a sun-lit paradise for wealthy vacationers. Victoria Hislop’s The Sunrise opens with the feel of a splashy beach read.

In the summer of 1972, the city of Famagusta on Cyprus is a sun-lit paradise for wealthy vacationers. Victoria Hislop’s The Sunrise opens with the feel of a splashy beach read.The title comes from that of a 15-storey coastal hotel being constructed by Savvas Papacosta and his wife, Aphroditi, a classic power couple blessed with wealth, attractiveness, and perfect taste as they cater to their guests’ every whim. The “holidaymakers,” cocooned in their carefree life of R&R, remain ignorant of the tensions between Turkish and Greek Cypriots.

There’s a lot of exposition piled on, and the storyline in the beginning offers all the glamour and depth of a dishy soap opera. If you don’t mind broad-brush characters, though, it’s worth sticking around to see what happens. The setting and history are both fascinating, and a timeline and note serve to alert readers of what’s to come.

In 1974, following a coup d’état in favor of annexation by Greece, and Turkey’s subsequent invasion of Cyprus, Famagusta was abandoned. Today its former tourist quarter, called Varosha, is a decaying ghost town.

Seen from the viewpoint of three families – the Papacostas, Georgious, and Özkans – The Sunrise takes readers step-by-step on a dramatic journey from Dynasty-style decadence to devastation.

It turns out the Papacostas’ marriage isn’t as solid as would seem, especially when Savvas’ suave right-hand man, Markos Georgiou, gets closer to Aphroditi. The novel’s most compelling aspect deals not with the ultra-rich but with the lives of ordinary citizens of Famagusta. In spite of their ethnic differences, Irini Georgiou, Markos’ mother, and hotel hairdresser Emine Özkan are firm friends, the matriarchs of their respective clans. Both fear they’ve lost sons to violence.

After the rest of the city’s residents flee in droves, only the Georgious and Özkans remain in Famagusta, in hiding from marauding soldiers. Together, they take up residence at the Sunrise, with its luxurious rooms and seemingly limitless food stores. It's a bit idealized; issues about electricity and sanitation aren't really addressed.

After the rest of the city’s residents flee in droves, only the Georgious and Özkans remain in Famagusta, in hiding from marauding soldiers. Together, they take up residence at the Sunrise, with its luxurious rooms and seemingly limitless food stores. It's a bit idealized; issues about electricity and sanitation aren't really addressed. Their interactions, hesitant at first, become warmer as they bond over traditional meals and the shared tribulations of family life. On the outside, however, the situation is dire. The suspense never lets up, as danger is ever-present.

Despite the shaky start, The Sunrise is a fast-paced, haunting novel about ambition, betrayal, love for family and place, and the commonalities shared among people on both sides of an ethnic divide. There are many poignant moments of togetherness and others of somber reflection, all evoked with sensitivity. As one character observes toward the end, looking out on her once-beautiful home: “This was not the city she knew. It was a place she did not recognize. Its soul had gone.”

The crumbling hotels of Famagusta, untouched and behind barbed wire since 1974.

The crumbling hotels of Famagusta, untouched and behind barbed wire since 1974."Famagusta2009 2" by Julienbzh35 - Own work.

Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons

The Sunrise was published in July by Harper Paperbacks ($15.99, 339pp). It was previously published by Headline in a different form (so says the title page) in the UK in 2014. Read more about "The Ghost Town of Cyprus" in the Famagusta Gazette; the experiences reported in the article echo those depicted in the novel. See also a February article from Newsweek discussing the history of Famagusta and recent talks on possible reunification.

For another novel about the Turkish invasion of Cyprus, see my review of Christy Lefteri's A Watermelon, a Fish, and a Bible.

Published on August 20, 2015 06:30

August 17, 2015

P. J. Brackston's Once Upon a Crime, a fairy-tale spoof with personality

A fairy tale sequel and crime novel with a light, humorous twist, P. J. Brackston’s Once Upon a Crime is hard to pigeonhole. For her premise, she takes the character of Gretel, first made famous by her childhood appearance with brother Hansel in the witchy Brothers Grimm story, ages her a few decades, and installs her as a private detective in 18th-century Bavaria.

A fairy tale sequel and crime novel with a light, humorous twist, P. J. Brackston’s Once Upon a Crime is hard to pigeonhole. For her premise, she takes the character of Gretel, first made famous by her childhood appearance with brother Hansel in the witchy Brothers Grimm story, ages her a few decades, and installs her as a private detective in 18th-century Bavaria. I’ve always gone for novels taking place in historical Germany, but must say up front that the setting here is quasi-historical at best. There are many willful anachronisms – waxing appointments, for example, and vodka martinis – plus a host of imaginary creatures, but the wacky combination of elements is part of its charm. When I heard the name of the place where Gretel hangs her shingle, the sleepy backwater of “Gesternstadt,” I was intrigued enough to read it.

Gretel’s a hefty gal who loves her Weisswurst and a good beer or two, and her perpetually inebriated brother Hans, who has never truly recovered from their childhood trauma, contributes to the household by cooking delicious meals. When Gretel agrees to help Frau Hapsburg locate her three kidnapped cats, she gets drawn into a web of danger involving a treacherous princess, a troll (the lives-under-a-bridge type) who has the hots for voluptuous women, and several unexplained murders. She also discovers that the fiery destruction of a local carriage-maker’s workshop is related to her case.

The storyline took a while to grab me. While I like a well-done spoof, I prefer historical fantasy novels with more actual history than this one offered. However, Gretel’s smart and sarcastic attitude soon won me over. A fashionista who appreciates the finer things in life, Gretel also detests the innate twee-ness of the world she’s forced to live in. I confess to being so distracted by all the amusing whimsy that I neglected to pay attention to the clues in what turned out to be a pretty decent mystery.

Historical purists may want to steer clear, but for those looking for an entertaining diversion from more serious fare, this could be just the ticket.

Once Upon a Crime was published by Pegasus in hardcover in July ($24.95/C$27.95, 245pp). The author also writes historical fiction with a mystical spin as Paula Brackston.

Published on August 17, 2015 13:00

August 14, 2015

Mystery, medicine, society, and scandal in 1850s Toronto: Janet Kellough's The Burying Ground

In 1851, there are odd goings-on at the Strangers’ Burying Ground outside Yorkville, a growing community north of Toronto. Graves are being disturbed, which infuriates sexton Morgan Spicer, but because the bodies are left intact, “resurrectionists” can’t be blamed. When Spicer runs into Luke Lewis, the new assistant physician to the elderly Dr. Christie, he realizes who can help him: Luke’s father, Thaddeus, an old acquaintance of Spicer’s who is known to love puzzles. On his return trips to Yorkville after preaching along the Yonge Street circuit, Thaddeus tries to catch the culprit.

In 1851, there are odd goings-on at the Strangers’ Burying Ground outside Yorkville, a growing community north of Toronto. Graves are being disturbed, which infuriates sexton Morgan Spicer, but because the bodies are left intact, “resurrectionists” can’t be blamed. When Spicer runs into Luke Lewis, the new assistant physician to the elderly Dr. Christie, he realizes who can help him: Luke’s father, Thaddeus, an old acquaintance of Spicer’s who is known to love puzzles. On his return trips to Yorkville after preaching along the Yonge Street circuit, Thaddeus tries to catch the culprit. The principal viewpoint in this 4th in the series, though, is Luke’s. He’s a charming character with aspects of his past he’d prefer to keep secret, even from his father, but a chance encounter with two young women draws him into situations that become steadily more worrisome. Luke is a straight-laced fellow, which creates some amusing episodes. True to his shy nature and Methodist upbringing, he’s alarmed at the thought of attending a soiree downtown (“If there was to be dancing, it was a good excuse to stay home”), but his employer knows that his mixing with the wealthier classes will help him fit in and increase their income. Dr. Christie’s burly and irascible housekeeper, Mrs. Dunphy, adds more doses of humor.

At times the historical backdrop gets lecture-y, particularly the long recap of the 1837 Rebellion, but otherwise mid-19th-century Toronto is richly evoked, with its political and religious divisions, bouts of deadly illness, the beginnings of urban sprawl, and the reputed miracle cures of Irish-born “Holy Ann” (a real person). Americans in particular may appreciate seeing how their country’s antebellum policies on slavery play out north of the border. Kellough also keeps readers on their toes by fleshing out her plot with unexpected turns throughout.

The Burying Ground was published in July by Canada's Dundurn Press, which sells books to both Canada and the US (304pp, paperback, $11.99 in both countries). I reviewed this for August's Historical Novels Review from a NetGalley copy. This is the first in the series that I've read, and I'd be interested to hear if anyone here has read the others.

Published on August 14, 2015 06:16

August 11, 2015

Shona Patel's Flame Tree Road, a rich journey toward social change in 19th-century India

Historical novels can give us the opportunity to experience distant times and places through the eyes of another. The most talented historical novelists can immerse us in an unfamiliar culture so completely that we become part of it, gaining empathy and understanding for the dilemmas its characters face.

Historical novels can give us the opportunity to experience distant times and places through the eyes of another. The most talented historical novelists can immerse us in an unfamiliar culture so completely that we become part of it, gaining empathy and understanding for the dilemmas its characters face. This is the case for Shona Patel’s Flame Tree Road, which is set mostly in 19th-century India. While it was written as a prequel to her debut, Teatime for the Firefly, it can also stand independently. Biren Roy, whose story is told from the early days of his parents’ marriage through his old age, is the man who becomes the beloved grandfather – Dadamoshai – of Layla from Teatime.

Biren’s character is formed through his experiences in both rural India and the hallowed halls of Cambridge. Due to his unique educational background, Biren serves as a bridge between these different cultures, members of whom occasionally treat him like an outsider, but he comes to embody the noblest qualities of both. He is immensely likeable, a man of gentle demeanor and refined manners. I rooted for him to overcome the obstacles he faced and find personal happiness.

For Biren, observing the shameful treatment of widows in his East Bengal village is the catalyst that directs the flow of his life. In his childhood, he sees how an old woman who lost her husband is forced to live under a banyan tree, while an old fisherman tells him bluntly that widows are “the cursed ones… the most wretched creatures on earth.” After the tragic early death of Biren’s father, he sees his beautiful young mother shunned and brought low, an action supported by the in-laws who loved her. The choice of ancient traditions over love and family is a pattern that repeats.

Fired up by this injustice, Biren knows that education is the key to social transformation and determines to become a lawyer and fight against the oppression of women in this regard. While the British educational model is highly respected, it’s also mistrusted, and Biren learns later that Britain has its own social problems to contend with. He forms friendships overseas and in India, but it’s only when he meets a schoolteacher's daughter named Maya that he finds the love he had sought.

Patel’s settings are evoked through richly woven images, from the generations-old craftsmanship at a potters’ village to the sensual fall of a woman’s hair. Her descriptions make the river of Biren’s home village easy to visualize: “crescent-shaped fishing boats skim the waters with threadbare sails that catch the wind with the hollow flap of a heron’s wing.” That’s just from the first page. The landscapes through which Biren moves come alive with a sense of wonder.

The last few chapters speed through Biren’s later life much too quickly, and I regretted that the novel wasn’t longer. The fact that I was left wanting more demonstrates the appeal of the characters. There are many moments of joy in Flame Tree Road, and others of abject sadness, all recounted with the flair of a natural storyteller as Patel brings us deeply into the life of an admirable man who dedicates himself to reshaping his world.

Flame Tree Road was published on June 30 by Mira ($14.95/C$17.95, 396pp). Thanks to the publisher for sending me a review copy at my request. For readers curious about Teatime for the Firefly , I reviewed it two years ago.

Published on August 11, 2015 11:34