Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 4

May 5, 2025

The spirit and the flesh: Emily Maguire's Rapture

Emily Maguire’s Rapture is an entrancing vision of a woman who unexpectedly rises to the height of influence in an exclusively male realm: the Roman Catholic church in the early Middle Ages.

Emily Maguire’s Rapture is an entrancing vision of a woman who unexpectedly rises to the height of influence in an exclusively male realm: the Roman Catholic church in the early Middle Ages. This new reinterpretation of the legend of Pope Joan explores the meanings of its title – spiritual, intellectual, and physical fulfillment – in the life of its subject, who finds she can’t deny her humanity and womanhood (“Oh, tiresome, greedy, needful body!”) while satisfying her cravings for scholarly nourishment.

The book is subdivided into sections whose headings come from a 13th-century chronicle, and I appreciated this nod to the limited record of her perhaps-existence. In 820s Mainz in the Frankish realm, Agnes, daughter of a man known as the English Priest and a pagan woman who died in childbirth, grows up absorbing the discussions in her father’s household, and the contents of his vast library, while viewing the wonders of nature.

The arrival of a young Benedictine monk, Brother Randulf, the most talented scribe at the Abbey of Fulda, shakes up her world. To her astonishment and pleasure, he acknowledges her thoughts have value and treats her like an equal. After her father’s death, Agnes asks him to take her to Fulda, in male disguise, so she can contemplate her learnings at leisure… or so she hopes.

This begins a deception that takes her from Fulda to the outskirts of Athens and at last to Rome, where her growing reputation leads her to become the right hand of Pope Leo IV. The violent impact of the Carolingian Civil War, when Charlemagne’s grandsons battled for control of land and empire, comes through well, as does the incessant politicking (which Agnes dislikes) within the pope’s inner circle.

Spiritually rich without being preachy or dense with theological arguments, the writing is a delight to read. It's an excellent vehicle for Agnes’s dramatic journey. We’re treated throughout to Agnes’s wise observations on her patriarchal environment, thanks to her unique viewpoint. “It is a revelation,” she thinks about the tedious rules and enforced humility of monastery life, “that these men struggle and need constant correcting in order to live as women must.” The ending, which fits with the Pope Joan legend, is transcendent.

Rapture was published by Sceptre in the UK, and by Allen & Unwin in Australia. In the US, the UK edition is sold on Kindle, which is how I purchased my copy. My choice to read this novel was inspired by recent news on papal history following the death of Pope Francis, as well as (related) the film Conclave, which I saw on Prime last weekend. I suspect Rapture will get an unintentional boost in readership thanks to world events!

Published on May 05, 2025 04:30

April 29, 2025

The Director, inspired by a true story, details one man's moral compromises in artistic creation

Smarting after a Hollywood flop, Austrian-born director G. W. Pabst, a Weimar cinema pioneer, returned to Europe. Trapped in Austria while visiting his mother when WWII broke out, he became enmeshed in Goebbels’ propaganda machine.

Smarting after a Hollywood flop, Austrian-born director G. W. Pabst, a Weimar cinema pioneer, returned to Europe. Trapped in Austria while visiting his mother when WWII broke out, he became enmeshed in Goebbels’ propaganda machine. Kehlmann (Tyll, 2020) uses this outline to construct a dark account of one man’s descent into fascist complicity, a path strewn with surrealistic scenarios and chilling self-justifications in favor of art.

The perspective shifts with each chapter, which keeps readers hyper-focused on each nightmarish step. The family’s Nazi-sympathizing caretaker at their Austrian home tyrannizes them; Pabst’s son Jakob begins bullying others. Pabst’s despairing wife, Trude, reluctantly joins an oppressive book club.

Ambitious yet passive, Pabst voices objections to working for the Reich but soon falls into line. “But once you get used to it and know the rules,” a colleague tells him, “you feel almost free.” The prologue foreshadows a mystery about his making of the film The Molander Case, and the reveal is shocking.

While it takes many fictional liberties, Kehlmann’s novel is purposefully unnerving and timely.

The Director, translated by Ross Benjamin, will be published by Simon & Schuster/Summit Books on May 6th, and I wrote this review for the April issue of Booklist.

The original German title is Lichtspiel ("Light-Play"), an older term used to refer to motion pictures, but which also has symbolic meaning for this novel. You can read an illuminating interview with Kehlmann at Hungarian Literature Online. As hinted in the review and in the interview, if you're expecting a fictional biography of Pabst, be aware that the storyline does diverge from his real life (and his family's) in multiple instances.

Published on April 29, 2025 12:54

April 24, 2025

Bits and pieces of historical fiction news

Here are some articles and other news items that caught my attention in the last week.

The 2025 Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction shortlist is out. The winner of this £25,000 Prize will be announced on June 12th at Abbotsford, the country house which was Scott's home in the Scottish Borders.

The Heart in Winter, Kevin Barry (Canongate/Doubleday US) - 1890s MontanaThe Mare, Angharad Hampshire (Northodox Press) - 1950s New YorkThe Book of Days, Francesca Kay (Swift Press) - Tudor England Glorious Exploits, Ferdia Lennon (Fig Tree/St. Martin's) - ancient GreeceThe Land in Winter, Andrew Miller (Sceptre) - 1962/63 EnglandThe Safekeep, Yael van der Wouden (Viking UK/Avid Reader) - postwar Holland

No Americans on the list this time, but half of the shortlist were published in the US, and two of the novels, The Heart in Winter and The Mare, are set here. You can read the judges' comments, with short plot synopses, at the link above.

On Jane Friedman's blog, author Laura Stanfill has a guest post explaining how she raised the stakes in her historical novel by following an editor's advice and moving a secondary character into the protagonist's chair. Read more at "Trust Your Instincts: Why Writing for Yourself Leads to Better Books."

In Welcome to Censorship, author Vanessa Riley speaks about how she was using the design tool Canva to develop slides for promoting her upcoming historical novel when the software flagged the word "enslaved," which describes her protagonist, as unsupported usage because it appeared to be "a political topic." Very disturbing.

From Sarah McCraw Crow's Substack, An Unfinished Story, the latest in her Midlife Author series is an interview with historical novelist Jane Healey about becoming debut author in her 40s, what it takes to pursue a writing career long-term, and the challenges she's faced.

Alina Adams, whose historical novel Go On Pretending is out on May 1st, writes about the ways she had success obtaining preorders, and where these attempts didn't work.

In the industry, people are getting mixed messages about the category "women's fiction." Editors aren't using the term, preferring "relationship fiction" or "book club fiction" instead. Agents are moving away from it too. But many writers and writers' associations embrace its usage, and the BISAC category of Fiction/Women still remains. You'll find the BISAC codes for books used by retailers like Amazon, digital catalogs like Edelweiss, and more. Read much more at Heather Garbo's Substack, Write Your Next Chapter. Her post, which examines relevant book deal announcements from Publishers Marketplace, also looks at the overlap between historical and women's fiction, and how books that fall into both categories may be labeled as one but not the other, making it hard to locate all new releases comprehensively. I'm always interested in avenues for discoverability for historical fiction, so I appreciated this post.

The 2025 Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction shortlist is out. The winner of this £25,000 Prize will be announced on June 12th at Abbotsford, the country house which was Scott's home in the Scottish Borders.

The Heart in Winter, Kevin Barry (Canongate/Doubleday US) - 1890s MontanaThe Mare, Angharad Hampshire (Northodox Press) - 1950s New YorkThe Book of Days, Francesca Kay (Swift Press) - Tudor England Glorious Exploits, Ferdia Lennon (Fig Tree/St. Martin's) - ancient GreeceThe Land in Winter, Andrew Miller (Sceptre) - 1962/63 EnglandThe Safekeep, Yael van der Wouden (Viking UK/Avid Reader) - postwar Holland

No Americans on the list this time, but half of the shortlist were published in the US, and two of the novels, The Heart in Winter and The Mare, are set here. You can read the judges' comments, with short plot synopses, at the link above.

On Jane Friedman's blog, author Laura Stanfill has a guest post explaining how she raised the stakes in her historical novel by following an editor's advice and moving a secondary character into the protagonist's chair. Read more at "Trust Your Instincts: Why Writing for Yourself Leads to Better Books."

In Welcome to Censorship, author Vanessa Riley speaks about how she was using the design tool Canva to develop slides for promoting her upcoming historical novel when the software flagged the word "enslaved," which describes her protagonist, as unsupported usage because it appeared to be "a political topic." Very disturbing.

From Sarah McCraw Crow's Substack, An Unfinished Story, the latest in her Midlife Author series is an interview with historical novelist Jane Healey about becoming debut author in her 40s, what it takes to pursue a writing career long-term, and the challenges she's faced.

Alina Adams, whose historical novel Go On Pretending is out on May 1st, writes about the ways she had success obtaining preorders, and where these attempts didn't work.

In the industry, people are getting mixed messages about the category "women's fiction." Editors aren't using the term, preferring "relationship fiction" or "book club fiction" instead. Agents are moving away from it too. But many writers and writers' associations embrace its usage, and the BISAC category of Fiction/Women still remains. You'll find the BISAC codes for books used by retailers like Amazon, digital catalogs like Edelweiss, and more. Read much more at Heather Garbo's Substack, Write Your Next Chapter. Her post, which examines relevant book deal announcements from Publishers Marketplace, also looks at the overlap between historical and women's fiction, and how books that fall into both categories may be labeled as one but not the other, making it hard to locate all new releases comprehensively. I'm always interested in avenues for discoverability for historical fiction, so I appreciated this post.

Published on April 24, 2025 05:30

April 18, 2025

Isabel Allende's My Name Is Emilia del Valle adds a new angle to her ongoing family saga

Allende has created many addictive sagas about the extended del Valle family and their intersections with history and one another. The eponymous Emilia, Allende’s addition to this notable clan, is one adventurous, gutsy woman.

The illegitimate daughter of a Chilean aristocrat and the Irish novice nun he seduced, Emilia grows up in San Francisco with her loving stepfather’s support, intrepidly working around gender restrictions. After penning dime novels pseudonymously, she becomes a human-interest columnist for the Daily Examiner and wangles an assignment as international correspondent for the impending Chilean Civil War of 1891, under her own byline.

Emilia’s first meeting with her long-lost father in Santiago is quite moving, and her time with the canteen girls who accompany President Balmaceda’s army echoes with their unsung courage. Allende expertly navigates through the violent chaos of battle and how it affects Emilia, whose romantic relationships also showcase her character growth.

Fans of Allende’s now-classic Daughter of Fortune (1999) and Portrait in Sepia (2000) will particularly welcome this offering, which is replete with Allende’s customary poetic storytelling.

My Name Is Emilia del Valle will be published by Ballantine in May; the translator is Frances Riddle. I contributed this review for Booklist's March issue.

I recommended this especially for readers of Allende's earlier novels because it's a new entry in the Del Valle saga, but mostly since significant characters from Daughter of Fortune and its sequel appear here too, which was a nice surprise. No spoilers here, but I'll be curious to see what other readers think about how this novel ends.

The illegitimate daughter of a Chilean aristocrat and the Irish novice nun he seduced, Emilia grows up in San Francisco with her loving stepfather’s support, intrepidly working around gender restrictions. After penning dime novels pseudonymously, she becomes a human-interest columnist for the Daily Examiner and wangles an assignment as international correspondent for the impending Chilean Civil War of 1891, under her own byline.

Emilia’s first meeting with her long-lost father in Santiago is quite moving, and her time with the canteen girls who accompany President Balmaceda’s army echoes with their unsung courage. Allende expertly navigates through the violent chaos of battle and how it affects Emilia, whose romantic relationships also showcase her character growth.

Fans of Allende’s now-classic Daughter of Fortune (1999) and Portrait in Sepia (2000) will particularly welcome this offering, which is replete with Allende’s customary poetic storytelling.

My Name Is Emilia del Valle will be published by Ballantine in May; the translator is Frances Riddle. I contributed this review for Booklist's March issue.

I recommended this especially for readers of Allende's earlier novels because it's a new entry in the Del Valle saga, but mostly since significant characters from Daughter of Fortune and its sequel appear here too, which was a nice surprise. No spoilers here, but I'll be curious to see what other readers think about how this novel ends.

Published on April 18, 2025 10:43

April 10, 2025

Are you missing the Tudor era? Check out these ten recent and upcoming novels

Are you a historical fiction fan looking back fondly on the years of Tudormania, when novels set in 16th-century England (especially about the royals) were eagerly scooped up by publishers? The good news is these books are still around, in smaller quantities perhaps, but novelists are still writing them, and readers still want them. During these fraught political times, when it's necessary to escape the news headlines periodically for one's own sanity, I've been finding myself gravitating toward earlier historical settings more often, including the Tudor era. Here are ten recent books set then, and I'll be posting reviews of many in the coming months.

A story of politics, philosophy, and gender-bending intrigue featuring Alexander "Sander" Cooke, a young man famed for playing female roles in Shakespeare's plays in Elizabethan London, and his best friend Joan, restricted from intellectual circles because she's a woman. William Morrow, Feb. 2025.

Jane (Parker) Boleyn, who has featured previously in the author's The Boleyn Inheritance and others, gets the full-length treatment in Gregory's next novel. Her return to the Tudor era explores Jane's motivations for her notorious actions. This is the US cover, perhaps designed to attract dark romantasy fans? HarperCollins, Oct. 2025.

This is the first historical novel I'm aware of about Mark Smeaton, the court musician accused of committing adultery with Queen Anne Boleyn (a treasonous act) and executed along with others caught up in the plot against Anne. His personal story is little known. SparkPress, May 2025.

A modern woman visiting an old Tudor mansion in Norfolk comes upon the story of Anne Dacre, later Countess of Arundel. She loses her beloved younger brother, perhaps at her stepfather's hands, and fights to take revenge. Boldwood, March 2025.

A trio of enterprising women band together to write poetry and plays secretly, and ask a certain rakish actor to pose as the author when their scheming attracts unwanted attention. This sounds like a fun spin on the "Shakespeare authorship" theme oft-expressed in historical fiction. Alcove Press, July 2025.

In this debut novel, Robert Smythson, the English architect famed for his design of Hardwick Hall, Wollaton Hall, and other Elizabethan manor houses, looks into a suspicious death discovered during the rebuilding of Longleat in Wiltshire. Glowing Log Books, Sept. 2024.

Another lesser-known Tudor personage claims the spotlight here: Anne, daughter of Henry VIII's good friend Charles Brandon, whose story of marital turmoil and clandestine romance is intertwined with that of a modern heiress and a remote country house in both women's lives. Boldwood, Jan. 2025.

Knowing Alison Weir's familiarity with Tudor-era notables, "the Cardinal" here could be none other than Thomas Wolsey, Henry VIII's right-hand man (until he notably fell from grace). She explores his surprising career and personal life, including his affections for his longtime mistress. Ballantine, May 2025.

Lady Margaret Clifford is a Tudor heir you may not have heard of; she was a granddaughter of Henry VIII's younger sister, Mary. The novel details the political, religious, and romantic intrigue surrounding Margaret as the English throne passes to Lady Jane Grey and then Mary I. This is first in a three-book series about women from the period. Sapere, Dec. 2024.

From the cover design and title, you might surmise that Wertman's latest Tudor novel retells the younger years of the future Elizabeth I in a narrative of hard-won wisdom and survival. I enjoyed her novel The Boy King, about Elizabeth's half-brother, Edward VI. Independently published, May 2025.

A story of politics, philosophy, and gender-bending intrigue featuring Alexander "Sander" Cooke, a young man famed for playing female roles in Shakespeare's plays in Elizabethan London, and his best friend Joan, restricted from intellectual circles because she's a woman. William Morrow, Feb. 2025.

Jane (Parker) Boleyn, who has featured previously in the author's The Boleyn Inheritance and others, gets the full-length treatment in Gregory's next novel. Her return to the Tudor era explores Jane's motivations for her notorious actions. This is the US cover, perhaps designed to attract dark romantasy fans? HarperCollins, Oct. 2025.

This is the first historical novel I'm aware of about Mark Smeaton, the court musician accused of committing adultery with Queen Anne Boleyn (a treasonous act) and executed along with others caught up in the plot against Anne. His personal story is little known. SparkPress, May 2025.

A modern woman visiting an old Tudor mansion in Norfolk comes upon the story of Anne Dacre, later Countess of Arundel. She loses her beloved younger brother, perhaps at her stepfather's hands, and fights to take revenge. Boldwood, March 2025.

A trio of enterprising women band together to write poetry and plays secretly, and ask a certain rakish actor to pose as the author when their scheming attracts unwanted attention. This sounds like a fun spin on the "Shakespeare authorship" theme oft-expressed in historical fiction. Alcove Press, July 2025.

In this debut novel, Robert Smythson, the English architect famed for his design of Hardwick Hall, Wollaton Hall, and other Elizabethan manor houses, looks into a suspicious death discovered during the rebuilding of Longleat in Wiltshire. Glowing Log Books, Sept. 2024.

Another lesser-known Tudor personage claims the spotlight here: Anne, daughter of Henry VIII's good friend Charles Brandon, whose story of marital turmoil and clandestine romance is intertwined with that of a modern heiress and a remote country house in both women's lives. Boldwood, Jan. 2025.

Knowing Alison Weir's familiarity with Tudor-era notables, "the Cardinal" here could be none other than Thomas Wolsey, Henry VIII's right-hand man (until he notably fell from grace). She explores his surprising career and personal life, including his affections for his longtime mistress. Ballantine, May 2025.

Lady Margaret Clifford is a Tudor heir you may not have heard of; she was a granddaughter of Henry VIII's younger sister, Mary. The novel details the political, religious, and romantic intrigue surrounding Margaret as the English throne passes to Lady Jane Grey and then Mary I. This is first in a three-book series about women from the period. Sapere, Dec. 2024.

From the cover design and title, you might surmise that Wertman's latest Tudor novel retells the younger years of the future Elizabeth I in a narrative of hard-won wisdom and survival. I enjoyed her novel The Boy King, about Elizabeth's half-brother, Edward VI. Independently published, May 2025.

Published on April 10, 2025 10:00

April 4, 2025

Haunting deceptions: Beth Ford's In the Time of Spirits

In the Time of Spirits is a novel of the late 19th-century spiritualist movement, seen from the perspective of those who performed seances for gullible audiences. Its plot takes unpredictable, often confounding turns, much like its strong-minded heroine. Are her actions irritating or all too fitting? They certainly offer much to think about!

In the Time of Spirits is a novel of the late 19th-century spiritualist movement, seen from the perspective of those who performed seances for gullible audiences. Its plot takes unpredictable, often confounding turns, much like its strong-minded heroine. Are her actions irritating or all too fitting? They certainly offer much to think about!After losing her parents in a house fire in Washington, DC, 22-year-old Adalinda (Addy) Cohart inherits a tidy sum. Although she’s grateful for the support of her longtime suitor, Arthur Simmons, Addy doesn’t want to wed anyone. She adores Marie Corelli’s mystical novels and sees mediums as important role models for independent, adventurous women.

Her interests lead her to New York City, alongside a female travel companion, and into the company of William Fairley, the handsome and charismatic assistant to the renowned Mrs. Alexi, whose spiritual talents seem fully plausible to the innocent Addy. Before long, Addy marries William, despite her previous aversion to wedlock, then accompanies him to London following an invite from a spiritualist organization. After being introduced to the secret tricks of his trade, Addy faces a life-changing choice.

The author’s smooth prose, unencumbered by elaborate descriptions, ensures a fast-paced read as Addy figures out what she wants and what she can tolerate. The text is so sparing of details, though, that the settings feel generic. Aside from notable landmarks, Manhattan, London, and Paris of the 1890s appear much the same. The theatrical performances Addy attends and the museum she visits remain nameless. The exceptions are the seances themselves. Rather selfish and a poor friend to others, Addy is often an unlikeable protagonist. However, by the dramatic turns of the finale, one might argue she is a memorable one.

This novel was published by Peony Books (the author's imprint) in 2024, and I wrote the review originally for the Historical Novels Review. The subject matter intrigued me, and so did the characters, even as their actions kept me guessing about where the plot was leading. I learn new things about authors' approaches to historical fiction with every book I read, and so it was with this book. Readers new to the genre might not mind or notice the absence of place-specific details, though this aspect stood out for me. I'd still read more by the same author, who has written other historicals as well.

Published on April 04, 2025 11:00

March 25, 2025

N. J. Mastro explores the tumultuous life of Mary Wollstonecraft in Solitary Walker

Mary Wollstonecraft is perhaps best known for two accomplishments: A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), a treatise that caused her to be remembered as the first feminist; and her status as the mother of Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein.

Mary Wollstonecraft is perhaps best known for two accomplishments: A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), a treatise that caused her to be remembered as the first feminist; and her status as the mother of Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein. As significant as these are, Wollstonecraft’s life was extraordinary for many other reasons. N.J. Mastro’s biographical novel explores them in depth, lavishing equal time on her innermost feelings and outward actions, as well as the tumult stirred up when they conflicted.

Wollstonecraft didn’t just talk the talk: she walked the walk, serving as an example of her belief that if women were given more than the limited education that society deemed appropriate, their intellectual and social development would flourish. Following an effective short prologue in which she tries and fails to protect her mother from her drunk father’s abuse, we meet Mary at twenty-eight, just as she’s being let go from her position as governess to an aristocratic Irish family’s daughters. The girls adore her, but her teachings are too broad and academic for their mother’s liking.

This setback spurs Mary to “make her own way in the world as a solitary woman,” heading to London to “live by her pen” in England’s literary capital. To earn a living, she accepts an invitation to review books for a progressive new journal – at a time when reviewing was competitive, well-paid, and mostly done by men!

Mary’s passions spring to life: her absorption into the lively community at the home of her publisher Joseph Johnson, where she holds her own at dinner conversations when she’s the only woman present; her determination to share her ideas through writing, despite Mr. Johnson’s gentle advice that she must publish anonymously; her growing irritation about the impositions of her family, always requesting money she’s hard-pressed to supply; and her curiosity about the dark eroticism of the oil painting The Nightmare, as well as its artist. She enjoys male friendships, but with many examples of marriage’s negative effect on women weighing on her mind, Mary guards herself when it comes to romantic and sexual relationships. The depth of her emotions, once they surface, catches her unaware.

The novel proceeds chronologically, focusing on key periods of Mary’s life and how her character transformed. Some of her exploits would be considered significant in any day and age, such as moving abroad to observe a new republic’s violent birth firsthand and directing her own solo trip through parts of remote Scandinavia. Mary’s time in France is especially dangerous given her nationality. Augmenting the stress and unease are the fraught personal circumstances in which Mary finds herself.

Mastro’s writing is skillful and precise, creating descriptions of settings and characters that linger. She has an eye for atmospheric details: “Everyone’s clothes felt damp; even the pages of their books had gone limp,” she writes of a hot, rainy summer day in Bristol. Nearly all the characters are historically documented; if you’re familiar with the period, you may figure out which one(s) are fictional. All is explained in an author’s note. This is a well-researched, admirable fictional portrait that will leave you amazed at the daring and vigorous way Mary moved through her world.

Solitary Walker was published by Black Rose Writing in February (reviewed from an ARC copy).

Published on March 25, 2025 04:00

March 19, 2025

The Long and Winding Road, an essay by Lorraine Norwood, author of The Solitary Sparrow

Continuing with the Small Press Month focus, I'm pleased to welcome Lorraine Norwood to Reading the Past with an essay about her long journey to publishing her debut novel. What do you do when you've chosen a compelling subject and have developed your fiction writing craft but find it impossible to break into the trend-focused market of traditional publication? Please read on, and please check out Lorraine's website for more information on her medieval historical fiction series, The Margaret Chronicles.

~

The Long and Winding RoadLorraine Norwood

I published my debut book in 2024 after years of writing. I submitted hundreds of queries, attended conferences, was accepted by an agent, submitted to the Big 5, got turned down, submitted to smaller houses, got accepted by a small publisher but said "no" because the contract was lousy, suffered the death of my biggest fan— my mother, got Covid and cancer, was released by my agent, pivoted to a reputable hybrid publisher—and then got accepted. Hurray! It only took me 38 years.

It was a long and winding road. Hard, with very deep potholes.

Why, you might ask, did you not shove the book in a drawer and forget writing? Well, I’ve had lots of jobs in my life in order to pay the electric bill but the job I do best is writing. And it’s the one that gives me the most joy. I didn’t give up because I couldn’t NOT do it. Even though it didn’t pay the electric bill.

Why, you might ask, did you not shove the book in a drawer and forget writing? Well, I’ve had lots of jobs in my life in order to pay the electric bill but the job I do best is writing. And it’s the one that gives me the most joy. I didn’t give up because I couldn’t NOT do it. Even though it didn’t pay the electric bill.

Since the first day my main character jumped into my head, I’ve seen a huge shift in the gatekeepers, a shift that has made it difficult for newbies to break into the traditional world of publishing.

Fourteen years ago I attended the HNS conference (my first) in San Diego and heard a group of editors and agents describe the chaotic changes in the traditional publishing world as the “new Wild Wild West.” I couldn’t be bothered with what the cowboys in New York City were doing. I had a book to get out. I had been working on it for years. All I had to do was get an agent at the conference, submit to the big boys, and voila! it was going to be a hit. Historical fiction readers were going to love it. I would be wined and dined, accompanied on book tours by my marketing agent, and get carpal tunnel syndrome from signing so many books.

Well, why NOT me? I did the work. Sat my butt in the chair. Worked on the craft. Got an agent. I rewrote sections of my manuscript for my agent, changed plotlines for prospective editors, and deleted scenes for editors who wanted the book sanitized. The negative responses went like this:

• The writing is top-notch, but nobody reads historical fiction anymore.

• It’s great writing, but it’s not saleable.

• Loved your characters, but we’re concerned about getting a return on our investment.

I did all the things you’re supposed to do and still NADA. After five years of trying, my agent, bless her heart, apologized and let me go.

That was the lowest, deepest pothole.

Jump to 2023. Traditional publishing was still not home on the range. If anything it was wilder than anybody predicted. Where were the chummy editor/writer consultations? Where were the book tours? Where were the marketing teams? Where were the new authors? Why were the big boys putting out the same people over and over again? And how, in all this chaos, with 2.2 million (and some say 3 million) books published yearly (according to UNESCO), can an author ever hope to climb to the top of the heap?

The truth is, you can’t. To think otherwise is delusional. At least that’s what a book coach and influencer told me during a Zoom call attended by hundreds of writers from across the globe. “You are delusional,” she said to me. Well, maybe she didn’t actually call ME delusional, just my thinking. Same thing. It hurt my feelings. But I realize now she was right. Except, maybe I wasn’t so much delusional as outdated and naive. I was waiting for others to take charge of my destiny, instead of me.

My book is NOT: historical fantasy, speculative historical fiction, historical crime, a retelling of Greek myths or historical romantasy. It’s not anything that the publishing powerful say they want.

author Lorraine NorwoodMy book is the story of one girl’s dogged pursuit to be the first female physician in England specializing in the care of women. The book is heavy on common people and light on the nobility. There aren’t any Tudors for another 200 years. The book is bloody, realistic, and gruesome in places. In fact, Goodreads contains this content warning: Abortion, miscarriage, death, misogyny, racial discrimination, gruesome medical procedures, and this review, “While I loved the grittiness of the story, a few scenes were a bit too crude for my reading preferences.”

author Lorraine NorwoodMy book is the story of one girl’s dogged pursuit to be the first female physician in England specializing in the care of women. The book is heavy on common people and light on the nobility. There aren’t any Tudors for another 200 years. The book is bloody, realistic, and gruesome in places. In fact, Goodreads contains this content warning: Abortion, miscarriage, death, misogyny, racial discrimination, gruesome medical procedures, and this review, “While I loved the grittiness of the story, a few scenes were a bit too crude for my reading preferences.”

Well, as the man says, “The past is a foreign country. They do things differently there.” Like die from childbed fever.

I now had a choice. I could spend more years of my life querying for an agent, querying the major and minor publishers, and waiting . . . and waiting or . . .

I was now 73 years old. I didn’t have time to wait.

I took an intense course on self-publishing. Self-publishing, no longer the red-headed stepchild of the author’s world, has gotten easier and more user friendly. But I decided my time could be spent more wisely by writing while I paid others to produce the book. After a lot of research and consultation with writer friends, I pivoted to hybrid publishing. One year later my book was born and out in the world.

At the recent History Quill 2025 virtual conference, panelists agreed that today traditional and indie publishing must go beyond mere writing and printing a book; multiple formats are increasingly important along with newsletters, blogs, email lists, social branding and authority on a subject.

And you thought all you had to do was write. Well, not anymore.

So, I’ll leave you with a few thoughts about the long and winding road.

There are many paths to publishing today. That’s the good news. You can send your work to agents or to small presses that don’t require an agent. You can send your work to hybrid presses or you can self-publish.

Do you have five years? Do you want to put it out there and get rejected or languish in a slush pile? Or do you want to see it out in the world in a year or possibly less?

For those of us who are "of a certain age," there is no question. We can’t wait. The finished book—that is the book that has been through beta readers, a developmental editor, a proofreader, a cover artist, and typographer—needs to be born as quickly as possible.

If you really want to do it, don’t wait. You’ll wait yourself into the grave. Morbid? Yes. But true. Sh*t happens. If you wait, it’s going to happen anyway. Don’t wait.

~

Lorraine Norwood is a North Carolina native living in the Blue Ridge Mountains with her 14-year-old yellow Lab who thinks food is more interesting than writing. Lorraine is working on The Margaret Chronicles, an historical fiction series set in 14th century England and France. The first of the series, The Solitary Sparrow, was published in 2024. She is hard at work on the sequel, A Pelican in the Wilderness.

Lorraine worked as a journalist in print and television for over 20 years before living the dream at the University of York in York, UK, where she earned a master’s degree in medieval archaeology. She has participated in excavations in York and at other sites in England, including a leper hospital.

She is a member of the Women’s Fiction Writers Association and the Historical Novel Society. She is happy that at long last, after two marriages, two children, twelve jobs, three college degrees, and twenty-three moves, she has a room of her own in which to write.

~

The Long and Winding RoadLorraine Norwood

I published my debut book in 2024 after years of writing. I submitted hundreds of queries, attended conferences, was accepted by an agent, submitted to the Big 5, got turned down, submitted to smaller houses, got accepted by a small publisher but said "no" because the contract was lousy, suffered the death of my biggest fan— my mother, got Covid and cancer, was released by my agent, pivoted to a reputable hybrid publisher—and then got accepted. Hurray! It only took me 38 years.

It was a long and winding road. Hard, with very deep potholes.

Why, you might ask, did you not shove the book in a drawer and forget writing? Well, I’ve had lots of jobs in my life in order to pay the electric bill but the job I do best is writing. And it’s the one that gives me the most joy. I didn’t give up because I couldn’t NOT do it. Even though it didn’t pay the electric bill.

Why, you might ask, did you not shove the book in a drawer and forget writing? Well, I’ve had lots of jobs in my life in order to pay the electric bill but the job I do best is writing. And it’s the one that gives me the most joy. I didn’t give up because I couldn’t NOT do it. Even though it didn’t pay the electric bill.Since the first day my main character jumped into my head, I’ve seen a huge shift in the gatekeepers, a shift that has made it difficult for newbies to break into the traditional world of publishing.

Fourteen years ago I attended the HNS conference (my first) in San Diego and heard a group of editors and agents describe the chaotic changes in the traditional publishing world as the “new Wild Wild West.” I couldn’t be bothered with what the cowboys in New York City were doing. I had a book to get out. I had been working on it for years. All I had to do was get an agent at the conference, submit to the big boys, and voila! it was going to be a hit. Historical fiction readers were going to love it. I would be wined and dined, accompanied on book tours by my marketing agent, and get carpal tunnel syndrome from signing so many books.

Well, why NOT me? I did the work. Sat my butt in the chair. Worked on the craft. Got an agent. I rewrote sections of my manuscript for my agent, changed plotlines for prospective editors, and deleted scenes for editors who wanted the book sanitized. The negative responses went like this:

• The writing is top-notch, but nobody reads historical fiction anymore.

• It’s great writing, but it’s not saleable.

• Loved your characters, but we’re concerned about getting a return on our investment.

I did all the things you’re supposed to do and still NADA. After five years of trying, my agent, bless her heart, apologized and let me go.

That was the lowest, deepest pothole.

Jump to 2023. Traditional publishing was still not home on the range. If anything it was wilder than anybody predicted. Where were the chummy editor/writer consultations? Where were the book tours? Where were the marketing teams? Where were the new authors? Why were the big boys putting out the same people over and over again? And how, in all this chaos, with 2.2 million (and some say 3 million) books published yearly (according to UNESCO), can an author ever hope to climb to the top of the heap?

The truth is, you can’t. To think otherwise is delusional. At least that’s what a book coach and influencer told me during a Zoom call attended by hundreds of writers from across the globe. “You are delusional,” she said to me. Well, maybe she didn’t actually call ME delusional, just my thinking. Same thing. It hurt my feelings. But I realize now she was right. Except, maybe I wasn’t so much delusional as outdated and naive. I was waiting for others to take charge of my destiny, instead of me.

My book is NOT: historical fantasy, speculative historical fiction, historical crime, a retelling of Greek myths or historical romantasy. It’s not anything that the publishing powerful say they want.

author Lorraine NorwoodMy book is the story of one girl’s dogged pursuit to be the first female physician in England specializing in the care of women. The book is heavy on common people and light on the nobility. There aren’t any Tudors for another 200 years. The book is bloody, realistic, and gruesome in places. In fact, Goodreads contains this content warning: Abortion, miscarriage, death, misogyny, racial discrimination, gruesome medical procedures, and this review, “While I loved the grittiness of the story, a few scenes were a bit too crude for my reading preferences.”

author Lorraine NorwoodMy book is the story of one girl’s dogged pursuit to be the first female physician in England specializing in the care of women. The book is heavy on common people and light on the nobility. There aren’t any Tudors for another 200 years. The book is bloody, realistic, and gruesome in places. In fact, Goodreads contains this content warning: Abortion, miscarriage, death, misogyny, racial discrimination, gruesome medical procedures, and this review, “While I loved the grittiness of the story, a few scenes were a bit too crude for my reading preferences.”Well, as the man says, “The past is a foreign country. They do things differently there.” Like die from childbed fever.

I now had a choice. I could spend more years of my life querying for an agent, querying the major and minor publishers, and waiting . . . and waiting or . . .

I was now 73 years old. I didn’t have time to wait.

I took an intense course on self-publishing. Self-publishing, no longer the red-headed stepchild of the author’s world, has gotten easier and more user friendly. But I decided my time could be spent more wisely by writing while I paid others to produce the book. After a lot of research and consultation with writer friends, I pivoted to hybrid publishing. One year later my book was born and out in the world.

At the recent History Quill 2025 virtual conference, panelists agreed that today traditional and indie publishing must go beyond mere writing and printing a book; multiple formats are increasingly important along with newsletters, blogs, email lists, social branding and authority on a subject.

And you thought all you had to do was write. Well, not anymore.

So, I’ll leave you with a few thoughts about the long and winding road.

There are many paths to publishing today. That’s the good news. You can send your work to agents or to small presses that don’t require an agent. You can send your work to hybrid presses or you can self-publish.

Do you have five years? Do you want to put it out there and get rejected or languish in a slush pile? Or do you want to see it out in the world in a year or possibly less?

For those of us who are "of a certain age," there is no question. We can’t wait. The finished book—that is the book that has been through beta readers, a developmental editor, a proofreader, a cover artist, and typographer—needs to be born as quickly as possible.

If you really want to do it, don’t wait. You’ll wait yourself into the grave. Morbid? Yes. But true. Sh*t happens. If you wait, it’s going to happen anyway. Don’t wait.

~

Lorraine Norwood is a North Carolina native living in the Blue Ridge Mountains with her 14-year-old yellow Lab who thinks food is more interesting than writing. Lorraine is working on The Margaret Chronicles, an historical fiction series set in 14th century England and France. The first of the series, The Solitary Sparrow, was published in 2024. She is hard at work on the sequel, A Pelican in the Wilderness.

Lorraine worked as a journalist in print and television for over 20 years before living the dream at the University of York in York, UK, where she earned a master’s degree in medieval archaeology. She has participated in excavations in York and at other sites in England, including a leper hospital.

She is a member of the Women’s Fiction Writers Association and the Historical Novel Society. She is happy that at long last, after two marriages, two children, twelve jobs, three college degrees, and twenty-three moves, she has a room of her own in which to write.

Published on March 19, 2025 05:00

March 13, 2025

The need for speed: Emma Donoghue's The Paris Express imagines the lead-up to a historic train disaster

On the morning of October 22, 1895, the Paris Express leaves the town of Granville in Normandy for its seven-hour, ten-minute trip to the capital. Unbeknownst to its many passengers, the train is hurtling toward a crashing halt. Donoghue (Learned by Heart, 2023) superbly portrays the lead-up to the Montparnasse derailment, a disaster memorialized in astounding photographs, as experienced by travelers of diverse nationalities and social classes.

On the morning of October 22, 1895, the Paris Express leaves the town of Granville in Normandy for its seven-hour, ten-minute trip to the capital. Unbeknownst to its many passengers, the train is hurtling toward a crashing halt. Donoghue (Learned by Heart, 2023) superbly portrays the lead-up to the Montparnasse derailment, a disaster memorialized in astounding photographs, as experienced by travelers of diverse nationalities and social classes. Among them are a mixed-race American painter aspiring to greater achievements, an Algerian coffee-seller, a young boy bravely journeying alone, a female physiology student who observes classic signs of disease in a teenage girl in her car, and married workmen who enjoy a unique partnership. Quietly, an anarchist on board weighs the right moment to strike.

Always balancing safety with keeping on schedule, crewmen feel pressured to make up any lost time. The pacing ramps up further midway through, the atmosphere tense.

Donoghue’s particular forte lies in showing how confined circumstances shape interactions. Her characterization is a marvel as she dexterously yet efficiently illustrates people’s outward appearances and innermost desires. In her hands, the novel’s long-ago setting becomes an exciting place buzzing with fresh life and technological ideas on the cusp of a new century.

The Paris Express will be published by Summit Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, next Tuesday, March 18th; I wrote this draft review for Booklist's February issue.

I won't link to articles about the notorious derailment since There Be Spoilers for this particular novel, but you can google it if you so choose!

Published on March 13, 2025 16:03

March 10, 2025

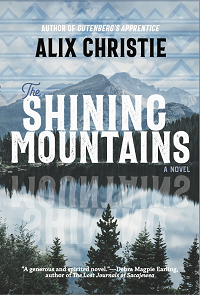

Our multicultural family history, a guest post by Alix Christie, author of “The Shining Mountains”

I'm very happy to have Alix Christie here on the blog with her essay about the family history behind her latest book, a family saga set in the Rocky Mountain West. Her debut,

Gutenberg's Apprentice

, was one of my favorite novels of 2014, and her second, The Shining Mountains, was just released in paperback by the High Road Books of the University of New Mexico Press. For additional information, please visit her website.

~

Our Multicultural Family HistoryAlix Christie

From an early age I was fascinated by the stories my Canadian grandmother told of her Scottish forbears in the Pacific Northwest, particularly one 19th century fur trader, Archibald McDonald, who married an alleged “princess” of the Chinook tribe. Decades later I would understand how offensive this fantasy depiction of Native wives of white men could be, and how common it unfortunately was. Yet as a child I was enraptured enough to draw a detailed family tree, showing that Archibald had indeed married Raven, a daughter of Chief Comcomly of the Chinook tribe. There the matter would have rested, if my younger brother, a historian and professor of literature, hadn’t turned up one day a decade ago with a boxful of books. He’d just written a scholarly paper on another distant relative, Duncan McDonald, and was gifting me his research. “For your next novel,” he said.

From an early age I was fascinated by the stories my Canadian grandmother told of her Scottish forbears in the Pacific Northwest, particularly one 19th century fur trader, Archibald McDonald, who married an alleged “princess” of the Chinook tribe. Decades later I would understand how offensive this fantasy depiction of Native wives of white men could be, and how common it unfortunately was. Yet as a child I was enraptured enough to draw a detailed family tree, showing that Archibald had indeed married Raven, a daughter of Chief Comcomly of the Chinook tribe. There the matter would have rested, if my younger brother, a historian and professor of literature, hadn’t turned up one day a decade ago with a boxful of books. He’d just written a scholarly paper on another distant relative, Duncan McDonald, and was gifting me his research. “For your next novel,” he said.

A quick count of the “Cast of Characters” of the book that eventually resulted adds up to more than fifty names. They include those Scots Highlanders, French missionaries, British bosses, American trappers, Norwegian, German and English immigrants, and Native Americans from five different tribes across the Rocky Mountain West. Though my research began with that one man — Duncan McDonald, son of our Scots great-great-great-uncle Angus and his Nez Perce wife Catherine—the story I discovered reached back several generations and across a vast expanse of the West, from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean. It all came together when I flew to Montana to meet my many cousins on the Flathead Reservation, all enrolled tribal members descended from Angus and Catherine.

Angus McDonald, 1860s, at the new international boundary between the U.S. and Canada

Angus McDonald, 1860s, at the new international boundary between the U.S. and Canada

Catherine McDonald (Kitalah—Eagle Rising Up, Nez Perce), studio portrait, 1860s Montana

Catherine McDonald (Kitalah—Eagle Rising Up, Nez Perce), studio portrait, 1860s Montana

Growing up in California public schools I had not the slightest idea of the deep pre-American history of our land. The story we were taught was one of pilgrims and triumph; the mechanics of “Manifest Destiny” and westward colonial expansion were not so much glossed over as ignored. Meeting for the first time Native Americans with whom I shared some drops of Scottish blood was therefore an extraordinary introduction to their history, both painful and proud. The five years I spent learning about their lives has been one of the richest experiences of my life. The Montana McDonalds welcomed me, offering advice and support; only with their generous help and a long and careful consultation with tribal authorities, was I able to breathe life into their family story as a novel.

The Shining Mountains recounts the life and times of this mixed-race family—half Scots Highlander, half Nez Perce, Mohawk and French—who were prominent in the last years of the fur trade between 1840 and 1860 in Washington, Oregon, Idaho and Montana. Angus McDonald was the last Chief Trader for the Hudson’s Bay Company in the vast chunk of territory that would become the northwestern United States. But it wasn’t his prominence that most amazed me. What struck me with even greater force was how incredibly multicultural was the mid-19th century world within which he and his family moved. We Americans have traditionally called our country a “melting pot” but on its western edge it was less melted than bubbling with many diverse peoples, all intermarrying and hunting and farming and trading together, Norwegian and Salish and Scottish and Yakama, French and Russian and yes—American. It was a Babel as well: many Native tribes communicated with one another through sign language, while the traders who bought furs from them used a pidgin they called “Chinook-wawa”.

Two of Angus and Catherine's children, Angus P. and Maggie McDonald,

Two of Angus and Catherine's children, Angus P. and Maggie McDonald,

in full Scottish regalia, 1870s Montana

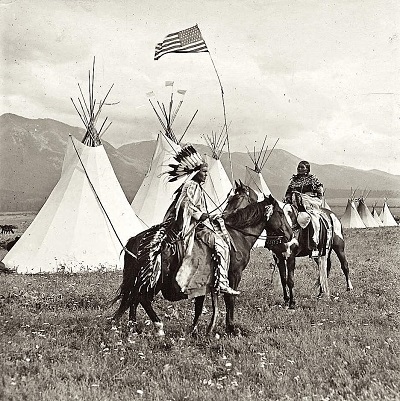

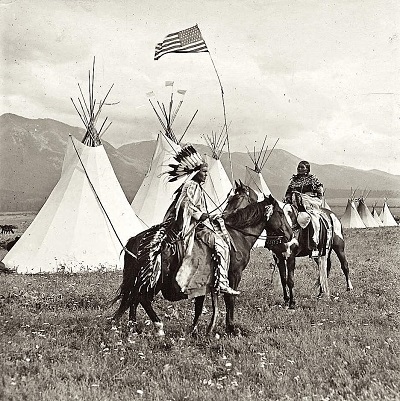

Angus and Catherine's son Duncan McDonald, with his wife

Angus and Catherine's son Duncan McDonald, with his wife

Louise “Quil-see” Shumtah (Salish),

in Native dress with American flag, 1870s Montana

This novel is about the love between two people of radically different backgrounds, yet sharing, paradoxically, a common culture of hunting and tight-knit family clans: Highlanders, too, were considered “savages” by the English who colonized Scotland. In North America families like theirs were put under incredible stress by the waves of Anglo migration that displaced Native people and forced them onto reservations. Yet against the odds they survived, to maintain their cultures and deep connection to their homelands. The “old Scotsman,” ancestor of many tribal members on the Flathead Reservation, remains a great source of pride. I was deeply moved when his great-grandson, the late Joe McDonald, the founder of Salish Kootenai College, and a great supporter of this project, described the book I wrote about Angus’ and Catherine’s life as “brilliant and invaluable.”

The author with the late Dr. Joe McDonald, Angus & Catherine’s great-grandson,

The author with the late Dr. Joe McDonald, Angus & Catherine’s great-grandson,

at the family cemetery at Post Creek, Montana (2016)

When I think now of the history of this country, I think of Joe, and of his cousin Maggie, the head of McDonald Ranch, and the rest of those descendants five and six generations later, every possible blend of indigenous and immigrant. America has always been a multicultural place, a mixing and mingling of different peoples and cultures. It’s a vital thing, today, to keep in mind.

~

The Shining Mountains (High Road Books/University of New Mexico Press) appeared in paperback in early March 2025. Also in e-book, audiobook and hardback wherever books are sold.

~

Our Multicultural Family HistoryAlix Christie

From an early age I was fascinated by the stories my Canadian grandmother told of her Scottish forbears in the Pacific Northwest, particularly one 19th century fur trader, Archibald McDonald, who married an alleged “princess” of the Chinook tribe. Decades later I would understand how offensive this fantasy depiction of Native wives of white men could be, and how common it unfortunately was. Yet as a child I was enraptured enough to draw a detailed family tree, showing that Archibald had indeed married Raven, a daughter of Chief Comcomly of the Chinook tribe. There the matter would have rested, if my younger brother, a historian and professor of literature, hadn’t turned up one day a decade ago with a boxful of books. He’d just written a scholarly paper on another distant relative, Duncan McDonald, and was gifting me his research. “For your next novel,” he said.

From an early age I was fascinated by the stories my Canadian grandmother told of her Scottish forbears in the Pacific Northwest, particularly one 19th century fur trader, Archibald McDonald, who married an alleged “princess” of the Chinook tribe. Decades later I would understand how offensive this fantasy depiction of Native wives of white men could be, and how common it unfortunately was. Yet as a child I was enraptured enough to draw a detailed family tree, showing that Archibald had indeed married Raven, a daughter of Chief Comcomly of the Chinook tribe. There the matter would have rested, if my younger brother, a historian and professor of literature, hadn’t turned up one day a decade ago with a boxful of books. He’d just written a scholarly paper on another distant relative, Duncan McDonald, and was gifting me his research. “For your next novel,” he said.A quick count of the “Cast of Characters” of the book that eventually resulted adds up to more than fifty names. They include those Scots Highlanders, French missionaries, British bosses, American trappers, Norwegian, German and English immigrants, and Native Americans from five different tribes across the Rocky Mountain West. Though my research began with that one man — Duncan McDonald, son of our Scots great-great-great-uncle Angus and his Nez Perce wife Catherine—the story I discovered reached back several generations and across a vast expanse of the West, from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean. It all came together when I flew to Montana to meet my many cousins on the Flathead Reservation, all enrolled tribal members descended from Angus and Catherine.

Angus McDonald, 1860s, at the new international boundary between the U.S. and Canada

Angus McDonald, 1860s, at the new international boundary between the U.S. and Canada Catherine McDonald (Kitalah—Eagle Rising Up, Nez Perce), studio portrait, 1860s Montana

Catherine McDonald (Kitalah—Eagle Rising Up, Nez Perce), studio portrait, 1860s MontanaGrowing up in California public schools I had not the slightest idea of the deep pre-American history of our land. The story we were taught was one of pilgrims and triumph; the mechanics of “Manifest Destiny” and westward colonial expansion were not so much glossed over as ignored. Meeting for the first time Native Americans with whom I shared some drops of Scottish blood was therefore an extraordinary introduction to their history, both painful and proud. The five years I spent learning about their lives has been one of the richest experiences of my life. The Montana McDonalds welcomed me, offering advice and support; only with their generous help and a long and careful consultation with tribal authorities, was I able to breathe life into their family story as a novel.

The Shining Mountains recounts the life and times of this mixed-race family—half Scots Highlander, half Nez Perce, Mohawk and French—who were prominent in the last years of the fur trade between 1840 and 1860 in Washington, Oregon, Idaho and Montana. Angus McDonald was the last Chief Trader for the Hudson’s Bay Company in the vast chunk of territory that would become the northwestern United States. But it wasn’t his prominence that most amazed me. What struck me with even greater force was how incredibly multicultural was the mid-19th century world within which he and his family moved. We Americans have traditionally called our country a “melting pot” but on its western edge it was less melted than bubbling with many diverse peoples, all intermarrying and hunting and farming and trading together, Norwegian and Salish and Scottish and Yakama, French and Russian and yes—American. It was a Babel as well: many Native tribes communicated with one another through sign language, while the traders who bought furs from them used a pidgin they called “Chinook-wawa”.

Two of Angus and Catherine's children, Angus P. and Maggie McDonald,

Two of Angus and Catherine's children, Angus P. and Maggie McDonald, in full Scottish regalia, 1870s Montana

Angus and Catherine's son Duncan McDonald, with his wife

Angus and Catherine's son Duncan McDonald, with his wife Louise “Quil-see” Shumtah (Salish),

in Native dress with American flag, 1870s Montana

This novel is about the love between two people of radically different backgrounds, yet sharing, paradoxically, a common culture of hunting and tight-knit family clans: Highlanders, too, were considered “savages” by the English who colonized Scotland. In North America families like theirs were put under incredible stress by the waves of Anglo migration that displaced Native people and forced them onto reservations. Yet against the odds they survived, to maintain their cultures and deep connection to their homelands. The “old Scotsman,” ancestor of many tribal members on the Flathead Reservation, remains a great source of pride. I was deeply moved when his great-grandson, the late Joe McDonald, the founder of Salish Kootenai College, and a great supporter of this project, described the book I wrote about Angus’ and Catherine’s life as “brilliant and invaluable.”

The author with the late Dr. Joe McDonald, Angus & Catherine’s great-grandson,

The author with the late Dr. Joe McDonald, Angus & Catherine’s great-grandson, at the family cemetery at Post Creek, Montana (2016)

When I think now of the history of this country, I think of Joe, and of his cousin Maggie, the head of McDonald Ranch, and the rest of those descendants five and six generations later, every possible blend of indigenous and immigrant. America has always been a multicultural place, a mixing and mingling of different peoples and cultures. It’s a vital thing, today, to keep in mind.

~

The Shining Mountains (High Road Books/University of New Mexico Press) appeared in paperback in early March 2025. Also in e-book, audiobook and hardback wherever books are sold.

Published on March 10, 2025 05:00