Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 24

July 23, 2022

A look at Addison Armstrong's The War Librarian and the courageous American librarians serving in WWI

If one can measure a novel’s success by the emotions it draws from readers, the sophomore work by Armstrong (The Light of Luna Park, 2021) is very effective indeed. The trials her protagonists undergo, while pursuing their dreams and holding onto their integrity, evoke admiration and passionate fury on their behalf.

If one can measure a novel’s success by the emotions it draws from readers, the sophomore work by Armstrong (The Light of Luna Park, 2021) is very effective indeed. The trials her protagonists undergo, while pursuing their dreams and holding onto their integrity, evoke admiration and passionate fury on their behalf. In 1918, Emmaline Balakin leaves her sedate Dead Letter Office job to serve in France as a hospital librarian. The injured soldiers at Bazoilles-sur-Meuse are truly grateful for the reading material, though Emmaline is aghast at the treatment of Black servicemen and dismayed by the American government’s censorship regulations.

In 1976, Kathleen Carre, granddaughter of Emmaline’s friend Nellie, breaks gender barriers by enrolling in the U.S. Naval Academy. Between ridiculous uniform requirements (three-inch heels!) and torturous hazing from male classmates, the system seems determined to break her, but she persists.

Romance and long-held secrets provide additional intrigue in this increasingly powerful story. The values of intellectual freedom, antiracist activism, and female friendship are illustrated within their historical contexts, yet these themes couldn’t be timelier.

The War Librarian will be published on August 9th by Putnam in the US. I wrote the review above for Booklist's historical fiction issue (dated May 15th). My editor gave me the opportunity to select books from a list of options, and this was one of them. I chose it not only because the subject interested me, being a librarian myself, but also because the personal story of my library's namesake is relevant to the book's subject.

Mary J. Booth in her

Mary J. Booth in her WWI uniformThe library where I work, Booth Library at Eastern Illinois University, was named after Mary Josephine Booth (1876-1965). She was head librarian there for 41 years, from 1904-45, aside from the period (1917-19) when she served overseas during WWI as a volunteer with the American Red Cross and, later, the American Library Association. During her tenure at Eastern, the library was housed in the main administration building, and she campaigned tirelessly for the campus to construct its own freestanding library. Plans were formulated in 1942, and the new Mary J. Booth Library was finally open for business in 1950, five years after her retirement.

Over my own time at Booth Library, I've given many tours covering different aspects of the building's history, including Miss Booth's wartime service, but I hadn't realized how rare an accomplishment this was until I read The War Librarian. "Very few female librarians were sent to France before the end of the war," Armstrong writes in her author's note. In Paris, Miss Booth worked to catalog American books shipped overseas for U.S. soldiers, selecting reading material for men in hospitals and in the trenches. She also cataloged the books at General John Pershing's headquarters at Chaumont.

Needless to say, I'll be purchasing a copy of The War Librarian for my library's recreational reading collection once it's published!

Read more at these external sites:

From NPR: When America's Librarians Went to War.

From the Library History Buff Blog: Women Librarians and ALA's Library War Service in WWI (which has a photo of Miss Booth)

From the Daily Eastern News:

Published on July 23, 2022 10:30

July 15, 2022

Jessie Burton's The House of Fortune continues The Miniaturist in early 18th-century Amsterdam

Burton’s The Miniaturist (2014) was an international bestseller with a subsequent TV miniseries, and this keenly awaited sequel should more than fulfill expectations. Exhibiting the same finely etched atmosphere of historic Amsterdam, it deepens characterizations by bringing the action forward while illuminating the childhood of the original protagonist, Nella.

Burton’s The Miniaturist (2014) was an international bestseller with a subsequent TV miniseries, and this keenly awaited sequel should more than fulfill expectations. Exhibiting the same finely etched atmosphere of historic Amsterdam, it deepens characterizations by bringing the action forward while illuminating the childhood of the original protagonist, Nella. In 1705, secrets flourish in the Brandt house on the Herengracht canal. Nella’s mixed-race niece, eighteen-year-old Thea, who knows little about her mother or events before her birth, conducts a furtive romance with an unsuitable man. With money tight, Nella hopes to find Thea a rich husband who will improve their fortunes.

Thea’s father, Otto, has his own ideas, and their competing plans clash dramatically. Meanwhile, the miniaturist from the first book, whose designs are unnervingly perceptive, has returned, with gifts for Thea.

With an artistic eye, Burton explores women’s lives, socioeconomic concerns, and the ways they intersect. This volume has few supernatural elements; rather, the story emphasizes the effect of the miniaturist’s creations. Both heroines grow and change in this smartly written tale about family relationships and recognizing truth.

With an artistic eye, Burton explores women’s lives, socioeconomic concerns, and the ways they intersect. This volume has few supernatural elements; rather, the story emphasizes the effect of the miniaturist’s creations. Both heroines grow and change in this smartly written tale about family relationships and recognizing truth. The House of Fortune was published on July 7 in the UK by Bloomsbury. North American readers will have to wait a little longer; it's published here on August 30th, also by Bloomsbury.

I wrote this review for Booklist's historical fiction issue, which came out on May 15th. You might notice a pineapple on the US cover, at the top, and (without providing spoilers), this plays a role in the story.

Published on July 15, 2022 13:00

July 9, 2022

Hilary Mantel examines her childhood via fiction in Learning to Talk

Two-time Booker winner Mantel explores the haunted landscapes of her childhood in this anthology, first published in Britain in 2003. The six stories, set in 1950s-70s industrial northern England, read like personal essays but sifted through a fictional lens: she calls them “autoscopic” rather than autobiographical.

Two-time Booker winner Mantel explores the haunted landscapes of her childhood in this anthology, first published in Britain in 2003. The six stories, set in 1950s-70s industrial northern England, read like personal essays but sifted through a fictional lens: she calls them “autoscopic” rather than autobiographical. The narrators closely observe their young lives amidst many adult tensions and secrets, such as marital scandals and class, racial, and religious differences. Children’s playground squabbles become a microcosm of Protestant-Catholic frictions, and two girls’ experience getting lost in a junkyard induces musings on emotional rootedness. Standouts are the title story, about elocution lessons for social mobility, and “The Clean Slate,” which delves into the mutability of historical memory through reflections on a drowned village.

Mantel carves beauty out of bleakness, crafting brilliant metaphors with penetrating human insights. “The country through which they move is older, more intimate than ours,” she writes about children’s innate knowledge of deducing truth about their world. Read this collection alongside her memoir, Giving Up the Ghost (2003), for additional insight into her life and creative process.

Learning to Talk was published in the US by Henry Holt in June and has been receiving a great deal of critical attention for a book nearly two decades old; this marks the first US publication. Can the stories be called historical fiction? This depends on your definition. Some aspects take place close to 50 years before the time of writing, while other stories are more recent. I wrote this review for Booklist Online (published online on June 30). Mantel wrote a new preface for this latest edition.

Published on July 09, 2022 06:00

June 30, 2022

The Research for The Valley: Researching a World That Never Was, an essay by A. M. Linden

Thanks to author A. M. Linden for contributing an essay on creating a plausible historical world for her new novel, The Valley, second book in her Druid Chronicles series set in the British Isles in the 8th century. The Valley was published by She Writes Press on June 28th.

~

The Research for The Valley:

Researching a World That Never WasA. M. Linden

Book 2 of The Druid Chronicles expands on the premise that the remnants of a once powerful pagan cult have survived into the last years of the eighth century, a time when the conversion to Christianity is all but complete throughout the rest of the British Isles. While the other four books of the series are set in fictional but historically based Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, Llwddawanden, the valley of the book’s title, is entirely hypothetical—a place I conceived of as a lost world where its inhabitants live according to a system of beliefs dating back to the Iron Age. That said, it was always my intention to make this part of my characters’ story at least plausible, and I began my research with a broad review of the relevant academic and popular literature.

Book 2 of The Druid Chronicles expands on the premise that the remnants of a once powerful pagan cult have survived into the last years of the eighth century, a time when the conversion to Christianity is all but complete throughout the rest of the British Isles. While the other four books of the series are set in fictional but historically based Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, Llwddawanden, the valley of the book’s title, is entirely hypothetical—a place I conceived of as a lost world where its inhabitants live according to a system of beliefs dating back to the Iron Age. That said, it was always my intention to make this part of my characters’ story at least plausible, and I began my research with a broad review of the relevant academic and popular literature.

Although Druids do not appear in the historical record after the Roman conquest of the Gauls on the European continent, and the Celts in what is now England, they are described by Julius Caesar and others as members of a priestly class of polytheistic Celts that performed functions as bards, oracles, and healers as well as serving as judges and political advisors. Caesar further reported that becoming a Druid required a training period as long as twenty years. With that to go on, I turned to ethnographic studies of societies with comparable social roles and to the works of folklorists who have recorded and studied epics and folktales from around the world—focusing on creation stories, epic poetry, and folktales conveying cultural mores.

By then I knew that one of The Valley’s underlying issues was to be the internal tensions of a persecuted minority struggling to survive and to pass on deeply held beliefs, and I had settled on the three main protagonists—Herrwn, the shrine’s master bard, Ossiam, their oracle, and Olyrrwd, their physician—who shared a collective responsibility as advisors to the shrine’s chief priestess and as judges on its councils.

By then I knew that one of The Valley’s underlying issues was to be the internal tensions of a persecuted minority struggling to survive and to pass on deeply held beliefs, and I had settled on the three main protagonists—Herrwn, the shrine’s master bard, Ossiam, their oracle, and Olyrrwd, their physician—who shared a collective responsibility as advisors to the shrine’s chief priestess and as judges on its councils.

Herrwn, the novel’s viewpoint character, had his origins in what I’ve learned about bards as the keepers and transmitters of cultural traditions through oral sagas and poetry, Ossiam is more of a mix, part-shaman, part-trickster, while Olyrrwd has his counterparts in non-western healers as well as in pre-nineteenth-century medical practitioners.

From the first, I intended the series’ major conflict to be between my Druid cult’s devotion to the worship of a supreme mother goddess and the paternalistic monotheism of the Christian world outside their secluded sanctuary. There is documentation of goddesses having a significant role in pre-Christian Celtic religions but, to me at least, their function was not as dominant as I had in mind, so again I looked at the larger literature—ranging from speculation about the paleolithic “Venus” figurines found across the Eurasian continent to the views of modern-day Wiccans—blending what I learned into the theology that would govern life in the imaginary valley of Llwddawanden.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Ann Margaret Linden was born in Seattle, Washington, but grew up on the east coast, returning to the Pacific Northwest as a young adult. She has undergraduate degrees in anthropology and in nursing and a master’s degree as a nurse practitioner. After working in a variety of acute care and community health settings, she took a position in a program for children with special health care needs where her responsibilities included writing a variety of program related materials. In a somewhat whimsical decision to write something for fun, she began what was to be a tongue-in-cheek historical murder mystery involving Druids and early medieval Christians. It wasn’t meant to be long or involved, but the characters seemed to acquire lives of their own and their story grew to become The Druid Chronicles. Prior to her retirement, this remained an after-hours endeavor that included taking adult education creative writing courses and researching early British history, and was augmented with travel to England, Scotland, and Wales. Since then, the insistence of those characters on getting themselves into print has prevailed. Currently completing the final draft of the last book, the author lives with her husband and their cat and dog in the northwest corner of Washington state.

For more information, visit the series website.

~

The Research for The Valley:

Researching a World That Never WasA. M. Linden

Book 2 of The Druid Chronicles expands on the premise that the remnants of a once powerful pagan cult have survived into the last years of the eighth century, a time when the conversion to Christianity is all but complete throughout the rest of the British Isles. While the other four books of the series are set in fictional but historically based Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, Llwddawanden, the valley of the book’s title, is entirely hypothetical—a place I conceived of as a lost world where its inhabitants live according to a system of beliefs dating back to the Iron Age. That said, it was always my intention to make this part of my characters’ story at least plausible, and I began my research with a broad review of the relevant academic and popular literature.

Book 2 of The Druid Chronicles expands on the premise that the remnants of a once powerful pagan cult have survived into the last years of the eighth century, a time when the conversion to Christianity is all but complete throughout the rest of the British Isles. While the other four books of the series are set in fictional but historically based Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, Llwddawanden, the valley of the book’s title, is entirely hypothetical—a place I conceived of as a lost world where its inhabitants live according to a system of beliefs dating back to the Iron Age. That said, it was always my intention to make this part of my characters’ story at least plausible, and I began my research with a broad review of the relevant academic and popular literature. Although Druids do not appear in the historical record after the Roman conquest of the Gauls on the European continent, and the Celts in what is now England, they are described by Julius Caesar and others as members of a priestly class of polytheistic Celts that performed functions as bards, oracles, and healers as well as serving as judges and political advisors. Caesar further reported that becoming a Druid required a training period as long as twenty years. With that to go on, I turned to ethnographic studies of societies with comparable social roles and to the works of folklorists who have recorded and studied epics and folktales from around the world—focusing on creation stories, epic poetry, and folktales conveying cultural mores.

By then I knew that one of The Valley’s underlying issues was to be the internal tensions of a persecuted minority struggling to survive and to pass on deeply held beliefs, and I had settled on the three main protagonists—Herrwn, the shrine’s master bard, Ossiam, their oracle, and Olyrrwd, their physician—who shared a collective responsibility as advisors to the shrine’s chief priestess and as judges on its councils.

By then I knew that one of The Valley’s underlying issues was to be the internal tensions of a persecuted minority struggling to survive and to pass on deeply held beliefs, and I had settled on the three main protagonists—Herrwn, the shrine’s master bard, Ossiam, their oracle, and Olyrrwd, their physician—who shared a collective responsibility as advisors to the shrine’s chief priestess and as judges on its councils. Herrwn, the novel’s viewpoint character, had his origins in what I’ve learned about bards as the keepers and transmitters of cultural traditions through oral sagas and poetry, Ossiam is more of a mix, part-shaman, part-trickster, while Olyrrwd has his counterparts in non-western healers as well as in pre-nineteenth-century medical practitioners.

From the first, I intended the series’ major conflict to be between my Druid cult’s devotion to the worship of a supreme mother goddess and the paternalistic monotheism of the Christian world outside their secluded sanctuary. There is documentation of goddesses having a significant role in pre-Christian Celtic religions but, to me at least, their function was not as dominant as I had in mind, so again I looked at the larger literature—ranging from speculation about the paleolithic “Venus” figurines found across the Eurasian continent to the views of modern-day Wiccans—blending what I learned into the theology that would govern life in the imaginary valley of Llwddawanden.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Ann Margaret Linden was born in Seattle, Washington, but grew up on the east coast, returning to the Pacific Northwest as a young adult. She has undergraduate degrees in anthropology and in nursing and a master’s degree as a nurse practitioner. After working in a variety of acute care and community health settings, she took a position in a program for children with special health care needs where her responsibilities included writing a variety of program related materials. In a somewhat whimsical decision to write something for fun, she began what was to be a tongue-in-cheek historical murder mystery involving Druids and early medieval Christians. It wasn’t meant to be long or involved, but the characters seemed to acquire lives of their own and their story grew to become The Druid Chronicles. Prior to her retirement, this remained an after-hours endeavor that included taking adult education creative writing courses and researching early British history, and was augmented with travel to England, Scotland, and Wales. Since then, the insistence of those characters on getting themselves into print has prevailed. Currently completing the final draft of the last book, the author lives with her husband and their cat and dog in the northwest corner of Washington state.

For more information, visit the series website.

Published on June 30, 2022 04:00

June 25, 2022

In the Face of the Sun takes its characters on a wild road trip through Civil Rights-era America

In late May 1968, when Francine “Frankie” Saunders climbs into her Aunt Daisy’s gorgeous new Ford Mustang, her aim is to flee Chicago and her abusive husband. She fears for her safety and that of the unborn child he doesn’t know about. Frankie barely knows Daisy, an irreverent, weed-smoking woman of nearly sixty who’s been estranged from Frankie’s mother for forty years, but she desperately needs Daisy’s help.

In late May 1968, when Francine “Frankie” Saunders climbs into her Aunt Daisy’s gorgeous new Ford Mustang, her aim is to flee Chicago and her abusive husband. She fears for her safety and that of the unborn child he doesn’t know about. Frankie barely knows Daisy, an irreverent, weed-smoking woman of nearly sixty who’s been estranged from Frankie’s mother for forty years, but she desperately needs Daisy’s help. On the wild road trip these two Black women take to Los Angeles, across two thousand miles with many bumps and detours, Frankie hopes to learn what caused the argument between Daisy and her mother. Daisy has another motive in mind for the journey’s end: revenge against someone from her past.

These two characters and their world jump off the page in radiant detail: their contrasting personalities, their distinctive looks (Daisy resembles a film star with her cat-eyed sunglasses, gingham dress, and perfect makeup), and their approaches to navigating America just two months after Martin Luther King’s assassination.

A second narrative, set in 1928, follows twenty-year-old Daisy Washington as she works as a chambermaid for L.A.’s Hotel Somerville, a prestigious facility catering to the Black elite. After her mother suffers a mental and physical breakdown, Daisy, a would-be journalist, aims to keep her younger sister, Henrietta, out of trouble while collecting celebrity gossip for a friend’s newspaper column. Both threads of this propulsive story ultimately lead to the same destination: the revelation of the terrible event that divided the Washington sisters.

In her second novel, Bryce shines light on notable people and events from American history, from civil rights activists Drs. Vada and John Somerville and the actor Stepin Fetchit to the painful wounds of Tulsa. The scenes are cinematically vivid, the language fresh and vibrant, the characters complicated and real.

Denny S. Bryce's In the Face of the Sun was published by Kensington in April (I'd reviewed it for the Historical Novels Review from a NetGalley copy). I also recommend her debut, Wild Women and the Blues.

Published on June 25, 2022 07:11

June 18, 2022

Marguerite Poland's A Sin of Omission evokes the repercussions of colonialism in 19th-century South Africa

A heart-wrenching story elevated through luminous writing, Marguerite Poland’s fictional tribute to a historical Black South African missionary was shortlisted for the 2020 Walter Scott Prize in its original edition.

A heart-wrenching story elevated through luminous writing, Marguerite Poland’s fictional tribute to a historical Black South African missionary was shortlisted for the 2020 Walter Scott Prize in its original edition. In 1880, Stephen Malusi Mzamane, deacon at Nodyoba, a remote mission in the hills of the Eastern Cape, prepares for a difficult journey to inform his mother about his older brother’s death. Most of the novel, though, looks back to reveal the circumstances leading him to this point. Found in the Donsa bush while foraging for food at age nine, the boy baptized “Stephen” is educated at the Native College in Grahamstown and later sent to the Missionary College in Canterbury, England, as part of the Anglican church’s plans to “Christianise the native.”

Though Stephen excels with his assignments, Poland depicts, in evocative words ringing with truth, how his progress in the Church and life is agonizingly held back by the bitter, systemic effects of colonialism. As a member of the “heathen” Ngqika people granted the rare privilege of a British education, he must simultaneously confront others’ high and low expectations for his conduct.

Readers can’t help but be moved by the internal conflict Stephen feels and his reactions to the burden of gratitude weighing him down. He also feels torn because his parishioners are from a different nation than he, and his superiors assume this doesn’t matter.

Readers can’t help but be moved by the internal conflict Stephen feels and his reactions to the burden of gratitude weighing him down. He also feels torn because his parishioners are from a different nation than he, and his superiors assume this doesn’t matter. All relationships are depicted with nuance: the two friendships Stephen cherishes across great distance; his challenging bond with brother Mzamo, once a promising scholar himself; and his preoccupation with a mysterious woman from a photograph. Respectful of her subject and his culture, Poland highlights the importance of Xhosa names and the language itself in Stephen’s world.

Remarkable on a sentence level and as a fully realized portrait of an honorable man, this is literary historical fiction of a high order.

A Sin of Omission was first published by Penguin Books South Africa in 2019, and the ebook version (which I had purchased) is available on Amazon (US). It was subsequently published by the British publisher EnvelopeBooks last month. I reviewed it for the Historical Novels Review in May. In addition to the Walter Scott Prize shortlisting, the novel won the 2021 Sunday Times award for fiction.

This story is not quite biographical fiction. Stephen is based on a real person whose history was known to members of her family, prompting her interest and further research into his life. Read more at the Sunday Times (South Africa) as well as Wanda Wyporska's interview with the author at the Historical Novel Society's website.

Published on June 18, 2022 13:52

June 13, 2022

Sisters of the Sweetwater Fury evokes early 20th-century Great Lakes women's lives, at sea and on land

With a strong sense of verisimilitude, Bryan takes readers into the raging heart of a historic event best experienced through fiction: the devastating Great Lakes Storm of 1913. As November settles in, during what’s been a low-casualty shipping season thus far, three sisters with deep roots in the region quietly endure the weight of marital and family expectations, not realizing how high the stakes will soon be raised for their very survival.

With a strong sense of verisimilitude, Bryan takes readers into the raging heart of a historic event best experienced through fiction: the devastating Great Lakes Storm of 1913. As November settles in, during what’s been a low-casualty shipping season thus far, three sisters with deep roots in the region quietly endure the weight of marital and family expectations, not realizing how high the stakes will soon be raised for their very survival. For the last decade, Sunny Colvin has cooked alongside her husband Herb, ship’s steward, aboard the steel freighter Titus Brown as it plies Lake Huron. When she hears a café is for sale in her home of Port Austin, Michigan, she fears disappointing Herb with her yearning to purchase it and leave shipboard life behind. Sunny’s younger sister Cordelia, a newlywed wanting to know her stoic lake-captain husband Edmund better, joins him on his journey across Lake Superior.

Back in Port Austin, a picturesque town on Michigan’s “Thumb,” oldest sister Agnes Inby, a widow of thirty-six, spends her days painting pottery and caring for her difficult mother, not letting herself dream about anything more, such as her unexpected feelings for the lighthouse-keeper’s sister, Lizzie. Adding to the already palpable tension of suppressed words and desires, the storm erupts at sea.

This is a real hang-onto-your-seat read. The action is nonstop intense as Sunny and Cordelia endure howling winds and freezing temperatures as water seeps in and fills their living spaces while the ships pitch from side to side. Inside at the Port Austin Life-Saving Station, where she grew up, Agnes prays the building will continue to hold. Bryan illustrates the interior lives of early 20th-century Great Lakes women as adeptly as she describes a ship’s layout and the visceral experience of this destructive storm.

Sisters of the Sweetwater Fury was independently published last October; I reviewed it for May's Historical Novels Review. An author I know recommended it to me, and the subject intrigued me because part of my family is from Michigan. It's definitely worth reading! This is the author's debut novel, and it's also received positive mentions from Publishers Weekly and the Blue Ink Review . I look forward to seeing what she writes next.

Published on June 13, 2022 05:00

June 9, 2022

Prepare for a TBR explosion with these guides to new and forthcoming historical novels

It's nearly summer in the US, a time when media outlets are recommending novels to read over the warmer months and through the rest of 2022 as well. Here are links to roundups that center on historical novels.

Library Journal's first historical fiction preview, compiled by Melissa DeWild, includes a whopping 86 upcoming titles, with short blurbs and comments from publishers. They're grouped mostly by category, with considerable focus on the world wars and subgroups thereof, plus others that span a wider range of eras and global settings. If you get paywalled, try registering for a free account with LJ.

Alida Becker's New York Times review roundup with new historical fiction to read this summer includes a good mix of commercial and literary historical fiction.

In Cosmopolitan, check out their choices of best historical fiction for 2022; most of these titles are already out, but not all.

The list at Business Insider mixes classic favorites and past award-winners with brand new selections: 28 in all that, they say, promise to "whisk you away to a different world."

Book Riot's coverage of historical fiction has been particularly strong lately. Last month, writer Kelly Jensen offered a guide to the best historical fiction organized by era, subgenre, age group, and other useful categories.

Historical mysteries are a favorite subgenre of mine. Writing for CrimeReads, novelist Christopher Huang has a piece responding to the question: "How do you decolonize the Golden Age mystery?" He recommends a wealth of new novels that examine the 1920s and '30s from viewpoints other than white and/or European. I especially liked these comments:

"... diversity is desirable because it represents a larger experience of the world and a fresh take on what we think we know. Especially in the context of historical fiction, an alternate viewpoint gives us a clearer understanding of what the world looked like. And why do we read fiction at all, if not for fresh experiences outside of what we know?"

Back in April, BuzzFeed published a guide to historical romances for Bridgerton fans.

In the Times (London), Antonia Senior has monthly roundups of the best new historical novels out that month (in the UK). Her May column is here, with settings ranging from ancient Greece to the 18th century. You can sign up for a free account to read these columns as they appear.

I'd be remiss if I didn't mention the Historical Novel Society's guides to forthcoming historical novels, compiled by Fiona Sheppard and Susan Firghil Park. The guide for adult titles goes through March 2023, and the children's/YA list goes through next January; these are regularly updated.

Library Journal's first historical fiction preview, compiled by Melissa DeWild, includes a whopping 86 upcoming titles, with short blurbs and comments from publishers. They're grouped mostly by category, with considerable focus on the world wars and subgroups thereof, plus others that span a wider range of eras and global settings. If you get paywalled, try registering for a free account with LJ.

Alida Becker's New York Times review roundup with new historical fiction to read this summer includes a good mix of commercial and literary historical fiction.

In Cosmopolitan, check out their choices of best historical fiction for 2022; most of these titles are already out, but not all.

The list at Business Insider mixes classic favorites and past award-winners with brand new selections: 28 in all that, they say, promise to "whisk you away to a different world."

Book Riot's coverage of historical fiction has been particularly strong lately. Last month, writer Kelly Jensen offered a guide to the best historical fiction organized by era, subgenre, age group, and other useful categories.

Historical mysteries are a favorite subgenre of mine. Writing for CrimeReads, novelist Christopher Huang has a piece responding to the question: "How do you decolonize the Golden Age mystery?" He recommends a wealth of new novels that examine the 1920s and '30s from viewpoints other than white and/or European. I especially liked these comments:

"... diversity is desirable because it represents a larger experience of the world and a fresh take on what we think we know. Especially in the context of historical fiction, an alternate viewpoint gives us a clearer understanding of what the world looked like. And why do we read fiction at all, if not for fresh experiences outside of what we know?"

Back in April, BuzzFeed published a guide to historical romances for Bridgerton fans.

In the Times (London), Antonia Senior has monthly roundups of the best new historical novels out that month (in the UK). Her May column is here, with settings ranging from ancient Greece to the 18th century. You can sign up for a free account to read these columns as they appear.

I'd be remiss if I didn't mention the Historical Novel Society's guides to forthcoming historical novels, compiled by Fiona Sheppard and Susan Firghil Park. The guide for adult titles goes through March 2023, and the children's/YA list goes through next January; these are regularly updated.

Published on June 09, 2022 10:11

June 7, 2022

Geraldine Brooks' multi-period latest novel, Horse, intertwines horse racing and hidden Black history

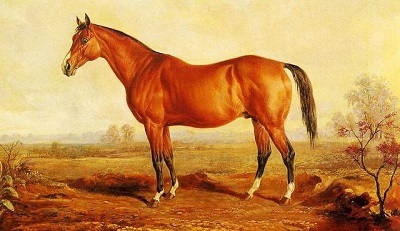

With exceptional characterizations, Pulitzer winner Brooks (The Secret Chord, 2015) tells an emotionally impactful tale centering on the life and legacy of Lexington, a bay colt who became a racing champion in mid-19th-century America.

With exceptional characterizations, Pulitzer winner Brooks (The Secret Chord, 2015) tells an emotionally impactful tale centering on the life and legacy of Lexington, a bay colt who became a racing champion in mid-19th-century America. Present at the horse’s birth is Jarret, an enslaved groom on Dr. Elisha Warfield’s vast Kentucky farm, and the pair develop an enduring bond. Jarret’s nuanced conversations with traveling equestrian artist Thomas Scott about the horse are mutually enlightening. Through Jarret and his father, a free Black man and expert horse trainer, readers encounter a wide range of injustices experienced by people of their race.

This perennially relevant theme extends into the 21st century via Theo, a Nigerian American art PhD student. His path intersects with Jess, an Australian-born scientist at the Smithsonian, after Theo saves an old equestrian portrait discarded by his neighbor.

Among the most structurally complex of all Brooks’ acclaimed literary historical novels, the narrative adroitly interlaces multiple eras and perspectives, including that of 1950s New York gallery owner Martha Jackson, who appears midway through.

From rural Kentucky to multicultural New Orleans, renditions of setting are pitch-perfect, and the story brings to life the important roles filled by Black horsemen in America’s past. Brooks also showcases the magnificent beauty and competitive spirit of Lexington himself.

Horse is published next Tuesday (June 14) in the US by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Random House. I submitted this starred review for Booklist, and it was published in the magazine's April 15th issue.

For those interested in seeing what Lexington looked like, below is a portrait by American painter Edward Troye in 1860, when Lexington was in his tenth year:

This novel is strongly based in history, although the modern-day characters are fictional, and little has come down to us about the real Jarret (meaning Brooks had to invent much about his character). Read more about the novel's historical background in a Q&A at Geraldine Brooks' website.

Published on June 07, 2022 17:16

May 31, 2022

Black Cake by Charmaine Wilkerson is a Caribbean saga revealing mysteries of family heritage

In 2018, after their mother Eleanor’s death, estranged siblings Byron and Benedetta “Benny” Bennett return to their California home for the memorial and to heed Eleanor’s final requests: that they listen together, in an attorney’s presence, to a recording Eleanor made in her last days, and sit down to share their mother’s traditional rum-soaked black cake when the time is right.

In 2018, after their mother Eleanor’s death, estranged siblings Byron and Benedetta “Benny” Bennett return to their California home for the memorial and to heed Eleanor’s final requests: that they listen together, in an attorney’s presence, to a recording Eleanor made in her last days, and sit down to share their mother’s traditional rum-soaked black cake when the time is right. After years of mutual hurt involving them and their late parents, Byron and Benny are wary of one another. They’re also unsure of their own paths forward. Byron, an African American oceanographer and TV personality, has endured a bad breakup, while Benny had distanced herself for serious personal reasons. Eleanor’s account dredges up mysteries from her youth and shakes up everything her children believed about their family.

This scenario may sound contrived, but it’s surprisingly easy to buy into because of how well the characters and their relationships are fleshed out. As Eleanor begins unspooling a tale about a young woman named Covey, a talented swimmer growing up on an unnamed Caribbean island in the ’60s, Byron and Benny are skeptical about its relevance. But the less said about the plot, the better, save that it spans miles and continents across decades and delves into themes of survival, exile, and the deep flavor of one’s heritage.

To call Black Cake innovatively layered is understating things. While the story may seem like it bounces between people and eras without a discernible pattern, soon you’ll realize that this talented debut author has her recipe under perfect control. A few pages here, a full chapter there, all added at just the right time. The revelations keep coming; by the end, every question is answered and then some. Eleanor is a marvel of a protagonist, and just like its subject, Black Cake is a satisfying dish worth sharing with others.

Black Cake was published by Ballantine in February (Michael Joseph is the UK publisher). I reviewed it for a past issue of the Historical Novels Review. It was a NY Times bestseller and a Read with Jenna book club pick, and Amazon tells me it's in production as a Hulu limited series. Read more at Deadline. I hadn't realized the novel was partly historical until a publicist emailed and offered me a NetGalley widget, and I'm glad she did.

Published on May 31, 2022 05:00