Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 136

October 31, 2011

Book review: Sarah Kernochan's Jane Was Here

Novels about reincarnation don't take up a large category. The dual scenarios - past and present - can help these works branch out to a wider readership, though, and historical events can impose on present-day happenings more directly than they can in a straightforward historical novel. That's one reason I like them.

As you can surmise from the cover art, Sarah Kernochan's Jane Was Here takes the form of a supernatural thriller. When a young woman calling herself Jane arrives in the glass factory town of Graynier, Massachusetts, everyone whose life she touches finds their life transformed in some way. Jane has memories of Graynier and says she's lived there before, though it no longer looks quite the way she remembers.

Not everyone is keen on having Jane around, especially when food starts disappearing from people's houses. Brett Sampson is the exception. A summer resident trying to reconnect with his son, he feels unexpectedly protective towards Jane and gives her a place to stay in his rented Victorian home (to his son's dismay). The town floozy and a deceitful handyman get drawn into Jane's web after her sudden appearance in the middle of the road leads to a car accident. The children of an Indian family who owns the local sleazy-dive motel get entangled in the mix, too.

Brett starts researching who Jane really is, as well as who she claims to be. There are many subplots, but everything is sharply delineated amid the rising suspense. As Jane slowly regains what seem to be memories of a tragic past life, she unwittingly sets in motion a plan to exact revenge on those who wronged her long ago.

By now you may be wondering about the book's historical aspect. Without giving too much away: Part 2 reveals the intimate letters of an impressionable 19th-century young woman who pursues her avid interest in an odd sect and its charismatic representative. "Gabriel Nation" is fictional, but with so many other peculiar religious revivals sprouting up in 1850s America, it fits right in.

Jane Was Here can be as quirky and eccentric as the people who inhabit its pages. The author has obviously poured a lot of attention into her characters, although she seems to care for them more than they care for each other (they aren't exactly society's most upstanding citizens). Jane's formality and propriety contrasts well with their careless lifestyles, though, and although I wasn't chilled by the creepy storyline, I followed it with great interest. Readers who enjoyed Brunonia Barry's The Lace Reader and M. J. Rose's Reincarnationist series may want to give this one a close look, too.

Jane Was Here was published by Grey Swan Press in June at $24.95 (hb, 296pp).

Published on October 31, 2011 18:46

October 25, 2011

Giveaway opportunity: Michelle Black's Séance in Sepia

Thanks to author Michelle Black, I have a new giveaway for readers of the blog. She will be offering a signed hardcover copy of Séance in Sepia, which I reviewed here on Sunday, to a randomly selected blog visitor.

Thanks to author Michelle Black, I have a new giveaway for readers of the blog. She will be offering a signed hardcover copy of Séance in Sepia, which I reviewed here on Sunday, to a randomly selected blog visitor.To enter, please leave a comment on this blog post, or on the associated post on this site's Facebook page if you prefer. Deadline is Friday, November 4th. This giveaway is open to all.

Best of luck to all entrants!

Published on October 25, 2011 04:00

October 23, 2011

Book review: Séance in Sepia, by Michelle Black

For her sixth historical novel, Michelle Black trades the vast landscapes of the historical and modern West for the social reforms and spiritualist beliefs of mid-19th century Chicago.

For her sixth historical novel, Michelle Black trades the vast landscapes of the historical and modern West for the social reforms and spiritualist beliefs of mid-19th century Chicago.When Flynn Keirnan spies a mysterious old photo at an estate sale, she immediately offers to buy it, believing the proceeds will help her dad's struggling used book business. The sepia-toned image of an unconventional dark-haired woman and two men appears to be a "spirit photograph." Back in the 1870s, séances were all the rage, as were photographers who claimed to be able to capture ghostly images on film.

Flynn lists the photo on eBay and sparks a bidding war. Startled, she does some research and learns about the trio's association with the scandalous "Free Love Murders." In 1875 Chicago, up-and-coming architect Alec Ingersoll was accused of killing the two people he loved most: Medora Lamb, his bohemian artist wife, and his best friend, Cameron Langley. All three lived together in the same house, which caused rumors to fly.

As Flynn uncovers their stories, with the help of a cute attorney with a family connection to the murder trial, a second woman over a century earlier is following a similar path. In exchange for an exclusive jailhouse interview with Ingersoll for her radical paper, notorious feminist Victoria Woodhull agrees to conduct a séance to learn the truth about how Medora and Cam died. An outspoken lecturer and advocate for sexual freedom, Victoria finds her investigation has unexpected repercussions for her personal life. "Free love," as it turns out, isn't so free after all.

The plot unfolds through a collection of scenes which include courtroom transcripts, journal entries, and straightforward narratives from both timelines. While some of them may seem tangentially related at first, all are cleverly drawn together just in time for a suspenseful finale. Along the way, the novel provides fascinating tidbits on episodes from 19th-century social history, from the unorthodox practices of New York's Oneida Community to early photography techniques.

The best part of the novel, though, is in seeing how the complex relationships between the characters play out on the page. Michelle Black has a gift for crafting realistic dialogue that highlights their personalities. Her close attention to detail, from the opulence of the Palmer House hotel where Victoria takes up residence to the snappy banter of her modern protagonists, makes both settings feel equally real.

Michelle Black's Séance in Sepia was published on October 21st by Five Star at $25.95 (hardcover, 322pp). Visit the author's website as well as her blog on the Victorian West.

Published on October 23, 2011 09:00

October 20, 2011

Winner of The Countess...

Earlier this week I drew the winning entry for Rebecca Johns' The Countess... and then forgot to post it on the blog. Oops - pardon my delay. One paperback copy will be going out to lucky commenter #1 - Amy! Congratulations, Amy, and I hope you'll enjoy the read.

Published on October 20, 2011 14:03

October 16, 2011

A look at The Ballad of Tom Dooley, by Sharyn McCrumb

Sharyn McCrumb's series of Ballad novels about the strong-minded residents and the scenic beauty of North Carolina's Blue Ridge Mountains usually make a point of debunking regional stereotypes. In its bleak and honest presentation of the roots of a local legend, The Ballad of Tom Dooley takes the opposite tack, showing many examples of why these stereotypes exist.

Sharyn McCrumb's series of Ballad novels about the strong-minded residents and the scenic beauty of North Carolina's Blue Ridge Mountains usually make a point of debunking regional stereotypes. In its bleak and honest presentation of the roots of a local legend, The Ballad of Tom Dooley takes the opposite tack, showing many examples of why these stereotypes exist.At the story's center are Tom Dula, a scrawny Confederate veteran with a talent for the fiddle and not much else, and Ann Foster Melton, his dark-haired (and married) lover, the most beautiful and most self-absorbed woman in all of Wilkes County. When plain-faced Pauline Foster comes down the mountain in 1866, offering to work for her Cousin Ann as a servant while getting treatment for syphilis, she deliberately spreads around resentment, jealousy, and lies along with her disease. The twisted chain of events eventually leads to the stabbing death of Laura Foster, a drab waif of a girl who's a distant cousin to both Ann and Pauline.

Living in these isolated mountains, nobody pays much attention to morality. Although Tom and Ann have been drawn to one another since childhood, neither is faithful or sees the need to be. James Melton, Ann's husband, is too bewitched by her beauty to care about her affair. Left to care for her siblings after her mother's death, Laura sleeps around with many men, Tom included, because there's nothing much better to do.

Zebulon Vance shares narration duties with Pauline, which provides some relief from her sociopathic viewpoint. In an attempt to bolster his legal career, he takes the case pro bono when Tom and Ann are jailed for Laura's murder. The Confederate ex-governor of North Carolina, Vance is a former mountain boy himself, though he took a different path in life than his clients. Looking back on events 20 years later, he speaks several times about his opposition to secession, his status as a U.S. Senator, and his reasons for choosing the woman he married; while he may be the only one in the bunch with brains and decency, he comes across as a bit of a snob.

The novel's sense of history is paramount, and McCrumb deftly evokes the violence that the end of the Civil War failed to suppress in the poverty-ridden Appalachians. However, with her primary narrator, Pauline, "not much moved by the beauty of nature," the gorgeous depictions of the region normally expected from her work aren't found to the same degree in this one.

A century of the folk process transformed this story into the classic murder ballad "Tom Dooley," which was made famous by the Kingston Trio in 1958. That version pinned the crime on Tom, but he isn't the perpetrator here – and the real killer shouldn't come as a surprise. Although this is a novel about a crime, it's not meant to be a mystery.

This scrupulously researched account gives a plausible scenario for how Laura Foster's murder may have happened – the author's note is generous and satisfying – and is worth reading for its re-creation of a real historical event. But with no reason to care about these lazy excuses for people, the promised tale of star-crossed romance just isn't there. Finally, knowing the reality behind the legend, one can't help but wonder if this sordid tragedy really deserved as much attention as it got. "That is the burden of this story," Vance himself says in the beginning, and although McCrumb is a talented writer, not even she manages to overcome it.

The Ballad of Tom Dooley was published by St. Martin's Press in September at $24.99 ($28.99 in Canada) in hardcover. The ARC was sent to me as part of LibraryThing's Early Reviewers program.

Published on October 16, 2011 15:01

October 8, 2011

Giveaway opportunity: Rebecca Johns' The Countess

Thanks to the Crown Publishing Group, I have the opportunity to offer a giveaway of Rebecca Johns' The Countess, biographical fiction about Erzsébet Báthory. It's newly out in trade paperback from Broadway ($15, 304pp).

Thanks to the Crown Publishing Group, I have the opportunity to offer a giveaway of Rebecca Johns' The Countess, biographical fiction about Erzsébet Báthory. It's newly out in trade paperback from Broadway ($15, 304pp).The Countess was a surprise hit for me when I read and reviewed it here last November. Erzsébet Báthory was the 16th-century Hungarian noblewoman for whom the term "bloodbath" could have been coined—rumors had it that she killed hundreds of her female servants and bathed in their blood—but Johns' novel is more of a creepy exploration of her psyche than a gory recounting of her supposed exploits. Read it and see how much you believe of her first-person story.

One copy is up for grabs. Please leave a comment on this post to enter; deadline Monday, October 17th, so that you should hopefully have it in time for Halloween. This giveaway is open to US and Canadian residents. Good luck to all!

Published on October 08, 2011 12:36

October 3, 2011

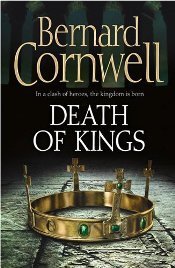

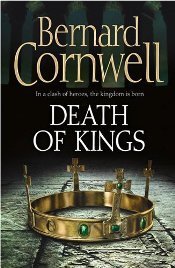

Book review: Death of Kings, by Bernard Cornwell

"It was Yule, 898, and someone was trying to kill me.

I would kill them instead."

Uhtred of Bebbanburg, the Saxon-born, Danish-raised warrior who has reluctantly become a fighter for Alfred of Wessex, is back in this sixth volume of the Saxon Stories. With his usual blend of confidence, physical strength, and gleeful sarcasm at the ready, he recounts a critical period in the making of England – and his involvement therein.

King Alfred is finally dying. The Danes lie in wait, eager to invade and tear apart the Christian realm he worked so hard to build. Uncertainty and suspicion are present from the outset, an effect that nicely mirrors the soon-to-be-fractured state of the kingdom. After foiling a murder attempt at his winter residence up north, Uhtred must return to duty when Alfred asks him to negotiate a treaty with King Eohric of East Anglia. The meeting place seems oddly chosen, and Uhtred smells something fishy.

King Alfred is finally dying. The Danes lie in wait, eager to invade and tear apart the Christian realm he worked so hard to build. Uncertainty and suspicion are present from the outset, an effect that nicely mirrors the soon-to-be-fractured state of the kingdom. After foiling a murder attempt at his winter residence up north, Uhtred must return to duty when Alfred asks him to negotiate a treaty with King Eohric of East Anglia. The meeting place seems oddly chosen, and Uhtred smells something fishy.

Uhtred has grown to admire Alfred over time, but he doesn't feel the same loyalty toward Alfred's heir, the ætheling Edward. Not only does Edward mistrust him, but Uhtred knows he will have a hard time convincing him that peace-making isn't the way to create a united Saxon country. Treachery and lies abound, not just from the enemy Danes but also from a rival claimant to the throne. While he faces Alfred's slow but impending demise as well as numerous threats to his own safety, Uhtred makes up his mind about his ultimate goal – and how he will attain it.

If this were purely an adrenaline-based saga, Death of Kings would be an impressively entertaining read. The strategies are laid out clearly, and the action is brutal and vigorous. Cornwell excels at depicting the "battle-joy" that comes over Uhtred as he prepares to face down a deadly foe. Even pacifists may find themselves caught up in the moment! The historical background is solid and vividly described, with authentic place names giving the setting a realistic feel.

Some of Uhtred's choices are wickedly clever, and they have his enemies running in frustrated circles. He delights in causing trouble, which makes for hilarious scenes. His taunting of the Danes at Snotengaham is meant solely to enhance his already fearsome reputation. He also has an excellent sense of how to annoy the ubiquitous priests who believe that victory can be won by prayer.

Death of Kings encompasses more than military encounters, however, and we experience a full range of emotions along with Uhtred: the assurance with which he leads his trusted men, the solemnity of his king's final moments, and the tenderness and pride Uhtred has for Æthelflaed, Alfred's daughter, whom he loves dearly. And while he always greets the possibility of war with eager anticipation, his encounter with a pagan sorceress in her otherworldly lair makes him shake in his boots. The consummate skill with which Cornwell evokes every aspect of Uhtred's story and character transforms an already exciting book into a truly outstanding one.

Death of Kings is published in October by HarperCollins UK at £18.99 (hardcover, 335pp). It will appear in the US next January from Harper at $25.99 (and good luck waiting that long).

I would kill them instead."

Uhtred of Bebbanburg, the Saxon-born, Danish-raised warrior who has reluctantly become a fighter for Alfred of Wessex, is back in this sixth volume of the Saxon Stories. With his usual blend of confidence, physical strength, and gleeful sarcasm at the ready, he recounts a critical period in the making of England – and his involvement therein.

King Alfred is finally dying. The Danes lie in wait, eager to invade and tear apart the Christian realm he worked so hard to build. Uncertainty and suspicion are present from the outset, an effect that nicely mirrors the soon-to-be-fractured state of the kingdom. After foiling a murder attempt at his winter residence up north, Uhtred must return to duty when Alfred asks him to negotiate a treaty with King Eohric of East Anglia. The meeting place seems oddly chosen, and Uhtred smells something fishy.

King Alfred is finally dying. The Danes lie in wait, eager to invade and tear apart the Christian realm he worked so hard to build. Uncertainty and suspicion are present from the outset, an effect that nicely mirrors the soon-to-be-fractured state of the kingdom. After foiling a murder attempt at his winter residence up north, Uhtred must return to duty when Alfred asks him to negotiate a treaty with King Eohric of East Anglia. The meeting place seems oddly chosen, and Uhtred smells something fishy. Uhtred has grown to admire Alfred over time, but he doesn't feel the same loyalty toward Alfred's heir, the ætheling Edward. Not only does Edward mistrust him, but Uhtred knows he will have a hard time convincing him that peace-making isn't the way to create a united Saxon country. Treachery and lies abound, not just from the enemy Danes but also from a rival claimant to the throne. While he faces Alfred's slow but impending demise as well as numerous threats to his own safety, Uhtred makes up his mind about his ultimate goal – and how he will attain it.

If this were purely an adrenaline-based saga, Death of Kings would be an impressively entertaining read. The strategies are laid out clearly, and the action is brutal and vigorous. Cornwell excels at depicting the "battle-joy" that comes over Uhtred as he prepares to face down a deadly foe. Even pacifists may find themselves caught up in the moment! The historical background is solid and vividly described, with authentic place names giving the setting a realistic feel.

Some of Uhtred's choices are wickedly clever, and they have his enemies running in frustrated circles. He delights in causing trouble, which makes for hilarious scenes. His taunting of the Danes at Snotengaham is meant solely to enhance his already fearsome reputation. He also has an excellent sense of how to annoy the ubiquitous priests who believe that victory can be won by prayer.

Death of Kings encompasses more than military encounters, however, and we experience a full range of emotions along with Uhtred: the assurance with which he leads his trusted men, the solemnity of his king's final moments, and the tenderness and pride Uhtred has for Æthelflaed, Alfred's daughter, whom he loves dearly. And while he always greets the possibility of war with eager anticipation, his encounter with a pagan sorceress in her otherworldly lair makes him shake in his boots. The consummate skill with which Cornwell evokes every aspect of Uhtred's story and character transforms an already exciting book into a truly outstanding one.

Death of Kings is published in October by HarperCollins UK at £18.99 (hardcover, 335pp). It will appear in the US next January from Harper at $25.99 (and good luck waiting that long).

Published on October 03, 2011 06:00

September 28, 2011

Guest post from Monika Schröder: Obituaries, Advertisements, and War Bulletins...

Today's guest post from Monika Schröder speaks to the historical background of her novel My Brother's Shadow, reviewed here on Tuesday. How did her archival research with Berlin newspapers inform her work, and how did she consult these primary sources while living half a world away? As a librarian who likes helping researchers with requests for older material, I found her essay especially enjoyable.

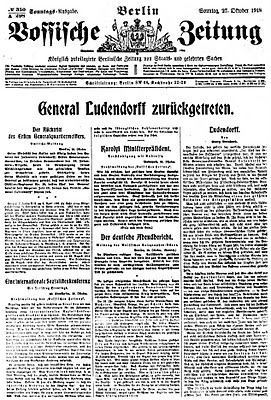

Obituaries, Advertisements, and War Bulletins – How Reading Berlin Newspapers from the Fall of 1918 helped me write My Brother's Shadow, by Monika Schröder

My new novel of historical fiction, My Brother's Shadow (Frances Foster Books/Farrar Straus Giroux, September, 2011), is set in Berlin 1918 during the last months of World War One. The book explores how war and the political transition following WWI affected regular people and children in particular.

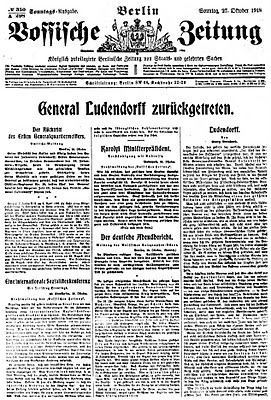

From reading secondary sources I had gained basic information about the situation among German civilians, but I needed to find more details of daily life in Berlin. A few excerpts of the Berliner Tageblatt and Morgenpost were available online, but most of those consisted of the front pages announcing important events such as the Kaiser's abdication or the armistice. I didn't find any searchable database that would give me access to the original Berlin newspapers of the year 1918.

When I contacted the German Newspaper Archive in Berlin, I learned that the digitization of most of the papers I was interested in had not been completed. The nice lady at the front desk invited me to visit the archive, explained which subway stop to get off and how much it would cost to make copies. I told her that I lived in New Delhi and wouldn't be able to come personally to the archive until the following summer.

But I needed those papers right away. I must have sounded desperate as she connected me to the director of the archive to whom I explained my predicament. I expected a tart 'no'; instead he told me that the archive had finished digitizing through the end of 1919 the Vossische Zeitung, an important liberal paper, published in Berlin. That was good news!

But when he asked how I could get to access the Vossische Zeitung from October 1918 to January 1919 he told me that they were not available online yet.

Now so close to my goal I was not ready to give up. "If you have them in digital format," I said. "Could you burn them onto a CD and send them to me?"

After a pause, he said, "That would be very expensive."

"How much?" I asked.

I won't disclose the sum. Let's just say he was right in his cost estimation, but I ordered them right away and three weeks later I was delighted to receive a package in the mail with the digitized editions of the Vossische Zeitung from October 14, 1918 to January 20, 1919.

I loved reading the newspaper. The official war report was printed daily on the front page, usually under an upbeat headline. But by the middle of October a discerning reader could see that the army leadership slowly began to disclose more and more of the German Army's dismal situation. The paper also printed obituaries. Every day numerous black framed notices informed the reader of the death of a young Karl or Friedrich who died "in honor of the fatherland" in France, Russia or Belgium.

I also studied the advertisements, which were very interesting and revealing. Due to the British blockade of the German harbors, Germany experienced severe food shortages. By 1918 many raw materials like coffee or cocoa were not available, and the lack of these products forced Germans to be inventive. Many "ersatz" (replacement) products were advertised. For example, I found an ad offering a class for housewives who wanted to learn how to make coffee from chicory and other ingredients. There were also numerous official calls for the collection of raw materials, such as metal, rubber, and cardboard. Others asked children to bring cherry and plum pits for a "Make Oil from Fruit Pits" campaign.

Commercial ads also illustrated the changing role of women in the war economy following the shortage of men. Traditionally considered the "weaker gender," women now were drafted to work in ammunition factories and conducted streetcars, and delivered milk and mail or moved heavy equipment as the woman in the following advertisement.

I was so fascinated by what I had read that the newspaper became an important part in the story. As an apprentice in a print shop of a Berlin newspaper, Moritz, the main character, reads the headlines of the paper he just helped print and thereby informs the readers of the state of affairs in Germany, October 1918. On the first page of the novel Moritz studies an official war report, knowing that the government is not allowing the truth to come out. He then meets Herr Goldman, a journalist who works for the paper and who takes a liking to Moritz and ultimately helps him to fulfill his dream to become a reporter like himself. When Moritz is sent out to report on an illegal demonstration he sees his mother among the speakers. He witnesses the police disturb the meeting, disperse the crowd and arrest the leaders. What happened to Moritz's mother? Read My Brother's Shadow to find out.

Obituaries, Advertisements, and War Bulletins – How Reading Berlin Newspapers from the Fall of 1918 helped me write My Brother's Shadow, by Monika Schröder

My new novel of historical fiction, My Brother's Shadow (Frances Foster Books/Farrar Straus Giroux, September, 2011), is set in Berlin 1918 during the last months of World War One. The book explores how war and the political transition following WWI affected regular people and children in particular.

From reading secondary sources I had gained basic information about the situation among German civilians, but I needed to find more details of daily life in Berlin. A few excerpts of the Berliner Tageblatt and Morgenpost were available online, but most of those consisted of the front pages announcing important events such as the Kaiser's abdication or the armistice. I didn't find any searchable database that would give me access to the original Berlin newspapers of the year 1918.

When I contacted the German Newspaper Archive in Berlin, I learned that the digitization of most of the papers I was interested in had not been completed. The nice lady at the front desk invited me to visit the archive, explained which subway stop to get off and how much it would cost to make copies. I told her that I lived in New Delhi and wouldn't be able to come personally to the archive until the following summer.

But I needed those papers right away. I must have sounded desperate as she connected me to the director of the archive to whom I explained my predicament. I expected a tart 'no'; instead he told me that the archive had finished digitizing through the end of 1919 the Vossische Zeitung, an important liberal paper, published in Berlin. That was good news!

But when he asked how I could get to access the Vossische Zeitung from October 1918 to January 1919 he told me that they were not available online yet.

Now so close to my goal I was not ready to give up. "If you have them in digital format," I said. "Could you burn them onto a CD and send them to me?"

After a pause, he said, "That would be very expensive."

"How much?" I asked.

I won't disclose the sum. Let's just say he was right in his cost estimation, but I ordered them right away and three weeks later I was delighted to receive a package in the mail with the digitized editions of the Vossische Zeitung from October 14, 1918 to January 20, 1919.

I loved reading the newspaper. The official war report was printed daily on the front page, usually under an upbeat headline. But by the middle of October a discerning reader could see that the army leadership slowly began to disclose more and more of the German Army's dismal situation. The paper also printed obituaries. Every day numerous black framed notices informed the reader of the death of a young Karl or Friedrich who died "in honor of the fatherland" in France, Russia or Belgium.

I also studied the advertisements, which were very interesting and revealing. Due to the British blockade of the German harbors, Germany experienced severe food shortages. By 1918 many raw materials like coffee or cocoa were not available, and the lack of these products forced Germans to be inventive. Many "ersatz" (replacement) products were advertised. For example, I found an ad offering a class for housewives who wanted to learn how to make coffee from chicory and other ingredients. There were also numerous official calls for the collection of raw materials, such as metal, rubber, and cardboard. Others asked children to bring cherry and plum pits for a "Make Oil from Fruit Pits" campaign.

Commercial ads also illustrated the changing role of women in the war economy following the shortage of men. Traditionally considered the "weaker gender," women now were drafted to work in ammunition factories and conducted streetcars, and delivered milk and mail or moved heavy equipment as the woman in the following advertisement.

I was so fascinated by what I had read that the newspaper became an important part in the story. As an apprentice in a print shop of a Berlin newspaper, Moritz, the main character, reads the headlines of the paper he just helped print and thereby informs the readers of the state of affairs in Germany, October 1918. On the first page of the novel Moritz studies an official war report, knowing that the government is not allowing the truth to come out. He then meets Herr Goldman, a journalist who works for the paper and who takes a liking to Moritz and ultimately helps him to fulfill his dream to become a reporter like himself. When Moritz is sent out to report on an illegal demonstration he sees his mother among the speakers. He witnesses the police disturb the meeting, disperse the crowd and arrest the leaders. What happened to Moritz's mother? Read My Brother's Shadow to find out.

Published on September 28, 2011 22:00

September 27, 2011

Book review: My Brother's Shadow, by Monika Schröder

In her young adult novel My Brother's Shadow, Monika Schröder creates a starkly realistic vision of Berlin at the end of World War I.

In her young adult novel My Brother's Shadow, Monika Schröder creates a starkly realistic vision of Berlin at the end of World War I.In 1918, sixteen-year-old Moritz Schmidt works as a printer for the Berliner Daily, which is obliged to publish patriotic bulletins from the German Reich even though its people know they're losing the war. With food rationing in place, a hearty meal is a distant memory. Instead, citizens stand in lines for bread and stretch their supplies by consuming turnip soup and ersatz coffee.

Moritz's home life is difficult. His father was killed at Verdun, his older brother Hans is off fighting at the Western Front, and his frail Oma (grandma) suffers from dementia. At the same time, his mother and sister attend secret meetings of the Social Democrats, who work to bring down the Kaiser and his oppressive regime. This introduces a note of hope into the narrative but causes confusion for Moritz, who doesn't know who to believe.

Succumbing to peer pressure and missing his brother, Moritz joins Hans's old gang, a group of bullies and thieves. After they threaten trouble for a new friend of his, a Jewish girl named Rebecca, his conscience begins to awaken. He also starts paying attention to his mentor at the paper, who sees potential in him as a journalist, and who considers his mother a hero for her outspoken stance. Then Hans comes home – crippled, angry, and eager to find a scapegoat for his and Germany's losses.

Moritz narrates the tale in a non-intrusive present tense. His innocence can make him seem younger than his years, but his honesty and openness draw readers into his gripping story. The pacing is brisk, and tension builds out of the bleak atmosphere.

Not surprisingly given the author's background (she grew up in Germany), she paints a detailed picture of the local geography and culture. Teenagers may find Moritz's coming-of-age journey and growing romance with Rebecca the most compelling, but adult readers may discover that Anna Schmidt, the woman he calls Mama, steals the show. She is strong, courageously optimistic, and devoted to her family, but not even she knows how to cure her wounded elder son.

This wise and provocative read doesn't offer up easy answers, which may be its greatest strength. The sobering ending makes it plain that for these characters and for Germany, the tale is far from over.

My Brother's Shadow was published today by Frances Foster Books/Farrar Straus & Giroux at $16.99 (hardcover, 217pp, with detailed author's note on the historical background). Look for a guest post by Monika Schröder later this week about the research process for her book.

Published on September 27, 2011 06:00

September 18, 2011

Langum Prize for American Historical Fiction: 1st shortlist announced

The Langum Charitable Trust, sponsor of the annual Langum Prize for American Historical Fiction, has announced a change in procedure. They have begun a shortlist process; the first shortlist will cover novels published in January-June of the prize year, and a second list will cover novels published in July-December.

The Langum Charitable Trust, sponsor of the annual Langum Prize for American Historical Fiction, has announced a change in procedure. They have begun a shortlist process; the first shortlist will cover novels published in January-June of the prize year, and a second list will cover novels published in July-December.For the first half of 2011, the shortlisted titles are:

Geraldine Brooks' Caleb's Crossing, set in 1660s Martha's Vineyard and Cambridge, Massachusetts, and centering on the friendship between a minister's daughter and a young man of the Wampanoag tribe;

Susan Vreeland's Clara and Mr. Tiffany, about Clara Driscoll, Louis Comfort Tiffany's chief designer at his New York glass studio in the 1890s.

Susan Vreeland's Clara and Mr. Tiffany, about Clara Driscoll, Louis Comfort Tiffany's chief designer at his New York glass studio in the 1890s.For more on both books, see the Langum Charitable Trust. To submit a novel for consideration, view the directions available at the site.

The prize is awarded annually to the "best book in American historical fiction that is both excellent fiction and excellent history." Recent past winners include Ann Weisgarber's The Personal History of Rachel DuPree, Edward Rutherfurd's New York, and Kathleen Kent's The Heretic's Daughter.

Published on September 18, 2011 09:32